At college, gaining the world but losing a home

As the cost of college continues to rise, the value of a college education, considered economically, will undergo greater scrutiny. While college graduates provide the state with more specialized labor, and make more money than non-graduates, some of these benefits are more than offset by one of its hidden costs: the fracturing of families.

Most institutions of higher learning like to see themselves serving broad multi-state and international constituencies. Drawing students from "all over" is often a point of pride. While there are some benefits to this approach, there are also profound costs, for such drawing deepens forms of deracination whose greatest beneficiaries are centralized powers, be they political or economic.

In the process, our colleges become "placeless." A geographically diverse academic enterprise doesn't commit itself to a concrete, embodied community, but directs its attention to an abstract "global society" that is no place at all. It thins the sense of moral obligation, substituting sentimental humanitarianism for the difficult virtues associated with neighborliness.

Most schools have elevated such sentimentalism into an orthodoxy. Martha Nussbaum's important work “Cultivating Humanity” became a standard defense of such principles, arguing that education ought to be geared toward global engagement and should intentionally erode local attachments, which because of their particularity become a source of division and strife. Her approach promulgated a cognitive "scorched earth" policy that erased from student's allegiances parental teaching and preferences.

One result is a widespread uprooting of students not only through their college years, but in the years after as well. States such as Michigan, suffering depressed labor markets, tend to experience a resultant brain drain as graduates move elsewhere looking for employment. A study commissioned by the Detroit Regional Chamber found that 37% of in-state college graduates were leave the state for greener pastures. The Michigan Economic and Workforce Indicators report indicates Michigan leads Midwestern states in losing college graduates.

"Despite the fact," the report says, "that U.S. mobility is at its lowest point since World War II, young, highly educated Michiganders continued to migrate out of the state in 2010, with the out-flow actually picking up pace since the prior year."

Political leaders, committed as they are to the view that all political problems are economic problems, will bemoan this loss, but do nothing to address the root causes connected to the wage-labor system or to an educational system dedicate to upward mobility. They will not see that, as Wendell Berry put it, the way up is ultimately the way out, and such a way will lead to the erosion of healthy communities. The impulse is to have students go to a better place, not make where they are a better place. The more rootless a person, the more they can be exploited in a system of centralized control.

Considering only the economic costs would be a failure of imagination. The social costs are much higher. Every year I witness parents go through gut-wrenching separation while dropping their children off at college, recognizing they have made it likely they'll never again live in the same town as their children. These children leave home behind, encouraged to seek something bigger and better, and in the process lose their connection with the most vital things in life.

For parents, the slow process of separation is a kind of amputation, an acceleration of the long letting go that begins the minute we take them to school and put them under someone else's tutelage. In some sense this is fitting and right. But the pain of loss is not mitigated by recourse to tropes about "emancipation” which see dissociation as the path to maturity and independence.

The costs pile up over time. Children are separated from parents and friends; after graduation they are separated again from the relationships they formed in those four years. Once they have children, those children are separated from the unconditional love of their grandparents, who are reduced to interlopers in an increasingly narrowed familial life, placing more pressures on these declining units, making them more fragile still. This widespread alienation - the loss of community and disconnectedness - are the defining features of our social life, and our colleges contribute mightily to this.

Better that Michigan colleges focus more on the needs of Michigan and less on those of the so-called global community. Freedom requires a deep associative life and is undermined by a stretching which holds individual achievement to be the highest good.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

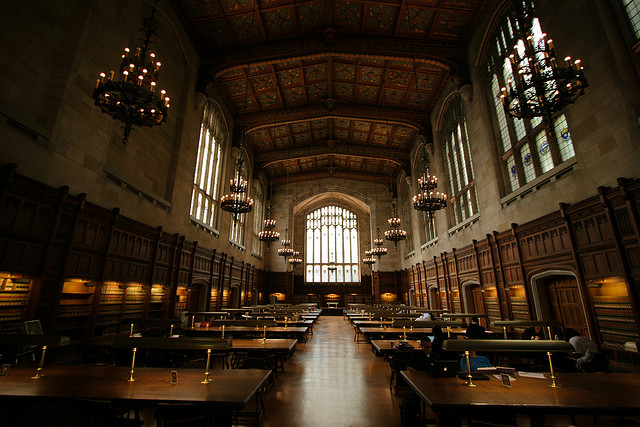

ROOTLESS U.: These hallowed halls may lead to the world, but they also contribute to the fracturing of communities. (Photo by Flickr user Bill Couch; used under Creative Commons license)

ROOTLESS U.: These hallowed halls may lead to the world, but they also contribute to the fracturing of communities. (Photo by Flickr user Bill Couch; used under Creative Commons license)