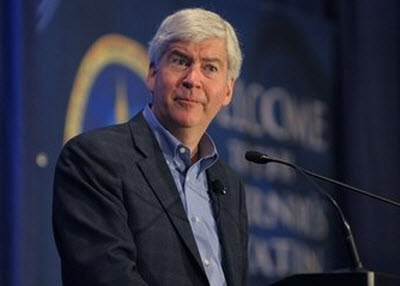

Snyder eyes future as his profile builds

LANSING — Gov. Rick Snyder has put an end to rumors that he plans to run for president next year.

But that doesn’t mean he’s not thinking about his political future.

A packed national travel schedule, which is positioned as a way to tout Michigan’s “comeback story,” is viewed by political watchers as Snyder’s effort to gain name recognition on a national stage. From California in late April to a New York visit late last week, Snyder is seemingly making traction in at least raising his profile.

But why is the term-limited Republican governor traveling the country to promote Michigan’s economic recovery — and Detroit’s emergence from bankruptcy — if he doesn’t eventually aspire to a national post?

Snyder offered a brief statement Thursday saying he is promoting Michigan’s economic success story to a national audience in an effort to lure new business.

“I do not have plans to run for president in 2016,” the statement said, adding that Snyder will focus on resolving “historic issues” at home.

One of those “historic issues” is the dramatic defeat of Proposal 1 on roads funding in Michigan. About 80 percent of statewide voters in the May 5 ballot proposal rejected the complicated plan to raise money for road work.

Plan B on roads

The morning after Proposal 1 was defeated, Snyder told reporters he planned to work quickly with the Legislature on an alternative, preferably one that does not involve asking voters to approve another ballot proposal. He said a delayed deal threatens to postpone construction schedules as roads continue to crumble.

Snyder won’t be able to build name recognition nationally if he’s stuck at home dealing with this unresolved road-funding plan, said Ron Fournier, a columnist with the Washington-based National Journal.

“He’s got to get this infrastructure thing straightened out,” Fournier said. “That was a big blow to him.”

Lawmakers put the roads deal to Michigan voters after failing to come up with a funding plan on their own. Proposal 1 would have raised more than $1.2 billion to fix the state’s decaying roads and bridges by raising the sales tax from 6 percent to 7 percent and removing it from fuel sales, while also raising fuel taxes.

But it ran into trouble with voters in part because of its complexity. Besides roads, it also would have raised money for public schools, local governments and an income tax credit for low-wage workers.

Proposal 1 failed by the largest margin of any constitutional amendment since Michigan’s constitution was adopted in 1963, the Associated Press reported.

A Cabinet post?

Exactly what Snyder does now to deliver on that promise of a Plan B for roads may be one of the deciding moments of his governorship, and his long-term political prospects, some observers say.

There is speculation among analysts and political writers that a Cabinet post may be Snyder’s ultimate endgame. Snyder, however, will neither confirm nor deny he wants one. He said only that he will stay on the national speaking circuit, and that he’s proud of Michigan’s successes.

“I will continue to tell Michigan’s comeback story nationally because our reinvention should not be unique to just our state,” he said.

And in terms of the field of presidential candidates, Snyder told the Wall Street Journal last week that he was “watching who is in the candidate race, because we need a problem-solver in Washington,” adding later that he didn’t see such a problem-solver in the field.

Snyder isn’t a viable presidential candidate for 2016 because the Republican field is crowded with contenders who have better name recognition and more money in their war chests, Fournier said.

To be sure, Snyder does have successes to promote for a future run or other high-profile post.

He helped craft Detroit’s grand bargain during the city’s bankruptcy, a deal designed to lessen the blow from cuts to retiree pensions that included $195 million from the state and hundreds of millions more from foundations and the Detroit Institute of Arts.

“His big calling card is Detroit. Detroit is a hip, exciting, intriguing brand across this country, even in the world,” Fournier said. “The Detroit comeback story is something that everybody is watching, and that’s something that Snyder has unique claim to.”

Even though he’s not a national household name, Snyder is hailed in Republican circles for replacing the Michigan Business Tax with a 6 percent corporate income tax and for signing right-to-work legislation in December 2012, which prevents labor unions from requiring workers to pay dues as a condition of employment.

More than 12,000 union members and supporters protested the politically divisive right-to-work legislation at the Capitol. But signing the law earned Snyder stripes among more partisan Republicans.

Michigan’s economy also has rebounded since the recession. Unemployment, once the highest in the nation at more than 15 percent, fell to 5.6 percent in March, state data show. And, Snyder says, Michigan has added close to 400,000 private jobs as the state’s economy moves away from heavy dependence on auto manufacturing.

Political ambitions

Bill Ballenger, a former state lawmaker and founder of Lansing-based political newsletter Inside Michigan Politics, said if Snyder had joined the fray for the 2016 presidential bid, he would have struggled to convince a national electorate of his problem-solving prowess, he said.

“The real question is: Has he really ‘solved’ Michigan’s problems?” Ballenger asked. “I think many people would say there are a number of things that he hasn’t solved yet. Maybe he can solve them by the time he leaves office in 2018. Maybe not.”

Snyder’s eventual prospects as a Cabinet member or other Washington post could depend on who is elected president, said John Truscott, president of Lansing-based political consulting firm Truscott Rossman and an ex-aide to former Gov. John Engler. And what he’s doing now may well raise his profile in Washington, or serve as a platform for a post-government career.

“I wouldn’t doubt that some people get in the race just to be a player so they get mentioned, they get their agenda out there,” Truscott said.

But, he added, “I don’t think he would ever admit (it).”

Building a national profile

A former executive with computer company Gateway Inc., Snyder has a background in business, not politics. But he has proven an ability to tackle tough political problems, notably Detroit’s bankruptcy, Fournier said.

“Snyder might be somebody that would make sense to have on a ticket,” a Republican from a blue state, Fournier said. “If a Republican wins, he’d certainly be somebody who’d be mentioned as, and even on the short list for, a Cabinet post.”

That depends, he said, on two big “ifs” — whether Snyder can continue momentum on rebuilding Michigan and Detroit, including reforming the city’s troubled public schools, and whether he can raise his national profile.

Raising Snyder’s profile is the mission of a nonprofit entity led by Snyder supporters, including former Michigan Republican Party Chairman Bobby Schostak. The group recently created a 501(c)(4) nonprofit called Making Government Accountable to fund Snyder’s national trips. It’s not an official campaign fundraising arm but helps pay for his travel.

The travel effort is “a trial balloon,” Ballenger said. “They’re going to try and help him do what he wants to do for as long as he feels it’s something that looks acceptable.”

The national circuit includes a range of influencers; Snyder spoke April 27 on a panel discussion on Detroit’s bankruptcy at the Milken Institute’s Global Conference, and, according to The AP, had a packed schedule in New York late last week. He met with site selectors who help companies choose where to locate and hosted a reception at Detroit watch company Shinola’s flagship store in New York City, AP reported.

Schostak could not be reached for comment on this story. The resident agent on the nonprofit formed March 23 is Peter Ellsworth, a Lansing-based attorney with Dickinson Wright PLLC.

In the immediate term, Snyder’s main focus likely will be on roads.

He can recover politically, long-term, from Proposal 1’s rejection, Truscott said, adding that it took Engler multiple tries in the 1990s to pass Proposal A, which restructured property taxes and funding for K-12 schools.

To succeed, Snyder will need to pull House and Senate leaders aside to work through alternative proposals and lobby for votes, Truscott said. The Legislature won’t be able to raise the amount Proposal 1 would have without either a tax hike or significant budget cuts elsewhere in state government.

“When you have an accomplishment after a failure, the failure pretty quickly gets wiped away,” Truscott said. “The measure of a good deal is not everybody’s happy.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder has hit the road in recent weeks

Michigan Gov. Rick Snyder has hit the road in recent weeks