Agriculture's growth real, but not the stuff of myth

Late last winter, Gov. Rick Snyder officially dubbed March 17, 2011, as Michigan Agriculture Day.

The proclamation lauds the industry as “the source of virtually everything we eat each day,” and says it plays a “key role in the growth and reinvention of Michigan’s economy.”

It’s one of the ways that Snyder has singled out the agricultural sector for extra attention since taking office -- despite campaigning in part on an economic strategy that eschews targeted aid to industries.

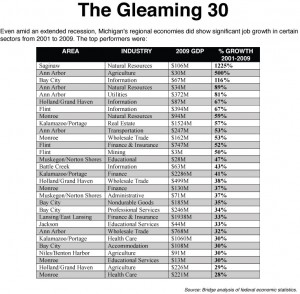

To be clear, there's good news on the farming front. Economic output of agriculture in Michigan grew by 59 percent over the past decade. That makes agriculture the runaway winner -- the fastest-growing sector of the past 10 years -- according to a Bridge Magazine analysis of federal gross domestic product data.

Some proponents even make the claim, repeated in Snyder's March 17 proclamation, that agriculture is the state’s second-largest industry. They add a highly questionable suggestion that agriculture deserves some credit for a quarter of Michigan’s jobs.

Some proponents even make the claim, repeated in Snyder's March 17 proclamation, that agriculture is the state’s second-largest industry. They add a highly questionable suggestion that agriculture deserves some credit for a quarter of Michigan’s jobs.

Critics, however, say this is a flawed belief based on an oft-cited Michigan State University review that pegs the state’s agri-food/agri-energy business at $71.3 billion a year and states that a quarter of the 4 million paying jobs in Michigan is somehow tied to the agriculture sector.

Agriculture has potent political myth

Google “Michigan agriculture $71.3 billion” and more than 6,100 hits pop up.

The claim is hogwash, state some economists. Only by the greatest stretch – including grocery stores, for example, or the trucks that haul produce as “agriculture” businesses – can the economic reach of Michigan’s farming community be deemed so pervasive. Yet the numbers have been repeated so often that they’ve taken on a life of their own.

“It’s absurd,” said Mitch Bean, former director of the House Fiscal Agency and now a partner in Eaton Rapids-based Great Lakes Economic Consulting LLC. “It attributes all sorts of things to the agricultural sector that shouldn’t be attributed there. And it way overinflates and the impact and influence of the ag sector on the economy.” (The Governor's Office did not respond to repeated requests from Bridge for comment on the use or validity of the MSU figures.)

“It’s absurd,” said Mitch Bean, former director of the House Fiscal Agency and now a partner in Eaton Rapids-based Great Lakes Economic Consulting LLC. “It attributes all sorts of things to the agricultural sector that shouldn’t be attributed there. And it way overinflates and the impact and influence of the ag sector on the economy.” (The Governor's Office did not respond to repeated requests from Bridge for comment on the use or validity of the MSU figures.)

Federal statistics reflect a more modest contribution of jobs, revenue and growth by the ag sector:

*According to the federal Bureau of Economic Analysis, agriculture including private crop and animal production, fishing, forestry and hunting in Michigan generated inflation-adjusted GDP of $2.73 billion in 2010. GDP measures the total market value of all final goods and services produced. That's up $1 billion from 2000, but that still moved the industry to only 0.8 percent of the state's GDP in 2010 (up from 0.5 percent in 2000). By contrast, $58.7 billion was generated by the manufacturing sector and $40 billion from the real estate sector. In fact, the arts and recreation sector in Michigan – which includes museums, performing arts and gambling -- is about on par with agriculture at $2.71 billion in 2010.

* Of the 16 major non-governmental sectors tracked by the BEA, agriculture in Michigan actually ranked 14th in GDP in 2010.

* According to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s 2007 census (the most recent data available) the Michigan acreage devoted to farming was roughly stable, though the number of farms increased from 53,315 in 2002 to 56,014 in 2007.

* A Bridge analysis of federal jobs data found about 70,000 farmers, managers, and field workers directly employed in agriculture statewide. But those jobs are projected to shrink by 2 percen by 2018 – and the average hourly wages are about $13 – or one-third less than the average for all jobs.

Snyder lavishes attention on ag

Still, Snyder already has singled out agriculture for extra attention. He’s appointed an agriculture expert to the executive committee of the Michigan Economic Development Corp. and renamed the state’s agriculture department the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, for starters.

Snyder also has expanded the 21st Century Jobs Fund to make some agricultural firms eligible for capital investment through the program which uses tobacco settlement money to “create and retain good jobs and a high quality of life.”

And as the governor’s press office wrote in March, “Governor Snyder’s first bill signings show commitment to agriculture, environment.” Snyder enacted the Michigan Agriculture Environmental Assurance Program, which protects farmers from fines and penalties for water pollution if they agree to follow certain environmental practices.

There’s no doubt that Michigan has a rich agricultural heritage and the unique climate effects of being two Great Lakes peninsulas afford the state a range of growing conditions ripe for a diverse crop mix and year-round sale of products ranging from soybeans to asparagus to Christmas trees.

Animal products are a key part of the sector, too; according to the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s most recent agricultural census, dairy products were the state’s top commodity in 2009, at more than $1 billion in gross sales, followed by corn, soybeans, greenhouse and nursery products, cattle and calves.

One chicken farm in the state, Herbruck’s Poultry Ranch in Saranac, supplies McDonald’s Corp. with all of the eggs it uses east of the Mississippi, according to Agriculture Department officials, and Michigan apples soon will be packed in Happy Meals as part of the fast-food giant’s nutritious-food efforts.

Critics say that while farming is an important part of the state’s economy, it’s hardly the most fertile ground for developing high-wage jobs, high-tech companies and other elements Michigan needs to fashion a new, post-manufacturing economy.

“There are jobs being generated, but agriculture is not going to turn around the entire economy of the state all by itself,” said David Oppedahl, a business economist who researches the agricultural and rural development sectors for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

How to reconcile the 70,000 jobs reflected in federal stats with the million-jobs claims of the industry in Michigan? The problem likely stems from over-attributing the multiplier effect of agricultural output, said Mark Partridge, an urban/rural policy expert and professor at Ohio State University. Sure, there is a spin-off value to farm produce, he said, but “the best way to look at it is, what would happen if you took away agriculture?

“You’d still have truck-driving jobs, because they’d be hauling food in from Ohio. You’d still have grocery stores,” he said. “Best practice is not to use the multiplier – we prefer to discuss the direct numbers.”

Bean agrees.

“If you treated every industry like agriculture was treated in that study, it would look like we had 15 million jobs in Michigan,” he said. “Certainly there is a need for a strong agriculture component in Michigan, but you’ve got to use the data correctly.”

Bob Boehm of the Michigan Farm Bureau understands the controversy about the numbers – though he doesn’t agree with critics -- but says, bottom line, there is a ripple effect statewide in terms of jobs and business retention due to farmers’ ability to supply raw materials.

“We produce $5 billion to $6 billion at the farm gate, but that doesn’t take into account the people working at Kellogg and Gerber and canning cherries here because they have access to product,” said Boehm.

And with emerging markets overseas opening up as China and other nations become more prosperous, he feels there’s an opportunity to seize right now in terms of new customers and cultivating new products like cranberries. Indeed, a just-out USDA report says Michigan’s agricultural exports, led by soybeans, grew about 10 percent in 2010 over 2009 levels, to about $1.75 billion. Michigan already ranks seventh in the U.S. in agricultural exports, shipping out one-third of its crops each year, the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development said.

Much of the rest feeds the state’s food-processing industry; the MDARD says it’s a $25 billion business that employs 133,000 people and nearly 1,600 businesses.

Traditionally, agriculture gets support that few other industries or occupations receive. There’s no state department of manufacturing, for example, or IT or biomed that champions those businesses the way for-profit growers are aided by the state.

The farmland preservation tax credit, for example, cost the state about $40 million in foregone property taxes in 2009. The credit, authorized by Public Act 116, survived the chopping block in fiscal 2012 budget cuts that saw higher education funding and film-industry incentives slashed.

Public and private economists say it’s impossible to determine the exact level of state funding of the agriculture industry because of the myriad agencies, services and processes involved – from publicly funded food-safety inspections to pest-control research at Michigan State University to regulatory and tax considerations

Some contend agriculture is a special industry that deserves extra resources and support from government. It’s tied to the very geography of the state, for one thing, and controls vital food sources. And, historically, it’s part of many Midwestern states’ very reason for existence, points out Partridge, harking back to when the region was settled for its farm potential.

“The agriculture industry just can’t pick up and move to China,” he said. “And while we need a lot fewer farmers than we used to, because they are so much more productive, this is a very prosperous time for the agriculture industry. Much of the jobs growth, for example, might be on the research side.”

Interestingly, the value of farming’s most basic ingredient -- land -- is rising, too. In a recent story, the Associated Press reported that investors nationwide are snapping up agricultural fields in response to increasing global demand for food and rising commodity costs -- and as a haven from securities with disappointing returns.

In Michigan, the average value per acre of farm land doubled from $1,704 in 1997 to $3,409 in 2007, according to U.S. Department of Agriculture statistics. That’s about in line with many current property listings, but the buyer in the AP story paid $9,300 apiece for 430 acres, and some current sellers are asking in the five-figure range.

Other growing agriculture careers might spin off education, technology and regulation, Partridge said.

“Rather than look at the average economic contribution of the industry, it might be better to see what individual projects and companies accomplish,” he said. “It’s not all about huge numbers ... we can find niches – organic, wine, local and so on – that can be very profitable.”

Editor's note: Mitch Bean is a member of the Bridge Board of Advisers.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!