The Big Flush: $180 billion vanishes from Michigan

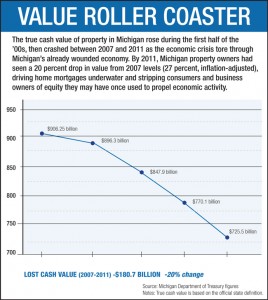

Michigan home- and business owners have lost an astounding $180 billion from the value of their properties over the past four years -- the result of auto company bankruptcies, a severe national recession and the worst state economy in more than 70 years -- according to an analysis of state data by Bridge Magazine.

Adjusted for inflation, property values have plunged 27 percent since 2007. In other words, Michigan homeowners and businesses have lost about $1 in every $4 of property value they once possessed.

The $180 billion loss in value is an amount five times larger than General Motors' market capitalization. It represents an average loss of $18,200 for every Michigan resident.

Experts say the real estate collapse could slow Michigan’s economic recovery for years as residential, commercial and industrial properties reset at much lower values.

“That may be the biggest story as far as Michigan’s economy is concerned,” said Michigan State University economist Charles Ballard.

Booming home prices and the easy availability of home equity loans in Michigan once allowed big-spending homeowners to use their property as virtual ATM machines. They pulled out hundreds of millions of dollars in equity to buy cars, big screen televisions and other purchases that kept the economy humming.

Not anymore. The crash in the value of Michigan’s homes and other property shut off the lights at this party.

(MORE FROM BRIDGE: Nest eggs go bad in Oakland County)

The total value of Michigan’s property has plunged 20 percent since topping out at $906 billion in 2007. Today, Michigan’s real estate is worth $726 billion, according to Bridge's review of Treasury Department data.

That has resulted in a variety of negative impacts for the state’s economy, schools and local governments.

Homeowners no longer have equity available to finance big-ticket purchases or to remodel their homes.

Unemployed homeowners or those with better job opportunities can’t go after jobs in other locations because they can’t sell their houses for as much as they need to pay off mortgages. And the high rate of foreclosures is pushing values down further.

Kelly Sweeney, chief executive of Coldwell Banker Weir Manuel, said the number of sales and prices of owner-occupied homes in Oakland County has started to rise as Michigan has added about 70,000 jobs this year.

But bank-owned foreclosures are offsetting those gains. He said about 50 percent of homes for sale in the county are owned by banks or government-owned lenders Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

How the government acts to dispose of those properties will determine how quickly residential values will recover, Sweeney added.

“Everybody’s worried about Freddie and Fannie,” he said.

Statewide, the average price of a home in August was $116,272, down 24 percent from the average price of $152,854 at the end of 2006, according to the Michigan Association of Realtors.

Meanwhile, school districts and local governments, heavily dependent on property taxes, are struggling to provide core services as property values have plunged.

Since their peak in 2007, home values have dropped in 70 of Michigan’s 83 counties. About 1,300 communities saw residential values decline in that period.

(BRIDGE CHARTS: Michigan's plunge in property value)

“Now you’re looking at communities that have gutted the numbers of public safety officers on the street,” said Paul Tait, executive director of the Southeast Michigan Council of Governments, a seven-county regional planning agency. “That is something that we’ve never seen before.”

Lower property taxes have put a few more dollars in homeowners' pockets. But much of that money likely is being spent by strapped consumers on necessities, such as nontaxable food and prescription drugs that don’t aid government coffers, said University of Michigan economist Don Grimes.

“It’s sort of a double whammy,” Grimes said. “The housing bubble really messed things up. It’s put us behind the eight ball in ways we hadn’t really thought about.”

“It’s sort of a double whammy,” Grimes said. “The housing bubble really messed things up. It’s put us behind the eight ball in ways we hadn’t really thought about.”

State and local governments will collect at least $1.2 billion less in property taxes this year than they did in 2007 because of declining property values and exemptions from the tax, according to a Treasury Department estimate.

School education tax revenues are estimated to have fallen $230 million in the past four years because of declining property values.

Fewer home sales in the sluggish housing market have nearly halved state real estate transfer taxes by $112 million since 2007.

And although Michigan has seen an uptick in jobs and economic growth this year, property values likely have not hit bottom.

A new SEMCOG projection shows that property values will continue to fall through at least 2014 in Southeast Michigan, although at a much slower rate.

The SEMCOG region accounts for about half of all economic activity in the state. It covers Livingston, Macomb, Monroe, Oakland, St. Clair, Washtenaw and Wayne counties.

Since 2007, five of its seven member counties have led the state in the decline of state equalized value, which is 50 percent of true cash value and traditionally was used in calculating property taxes.

But Proposal A, passed by voters in 1994, capped annual increases in state equalized value to 5 percent or the rate of inflation, whichever was less.

Schools and local governments now collect taxes based on Proposal A’s “taxable value” of property, which last year was about $48 billion less than state equalized value.

“Lower property taxes have put so much pressure on funding schools and local governments at a time when state revenues have declined,” Ballard said.

Oakland County saw the biggest drop in state equalized value, falling 32 percent since 2007. The other top losers were Macomb (-30 percent), Wayne, (-30 percent), Genesee (-30 percent), Lapeer (-28 percent), St. Clair (-27 percent) and Livingston (-27 percent).

“Devastating” is the word Hazel Park City Manager Edward Klobucher uses repeatedly to describe the impact plunging property values has had on his Oakland County community and others.

Hazel Park, a working-class community with a population of about 16,400, saw its state equalized value drop from $465 million in 2007 to just $233 million this year, a staggering 50 percent drop.

That was the second-biggest property valuation decline of any community in Michigan during the past four years. Pontiac, also in Oakland County, experienced the largest drop, losing 51 percent of its property value in the period.

Hazel Park also lost 13.4 percent of its population -- some 2,500 residents -- over the past decade as the state’s economy plummeted.

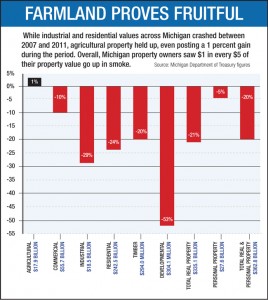

Statewide, industrial property experienced the largest decline in value, falling 29 percent, as hundreds of factories ranging from auto assembly plants to family-owned tooling shops closed their doors in the Great Recession.

The only sector that grew in value over the past four years was agricultural property, which posted a slight 1 percent increase from 2007 to $17.9 billion this year.

Commercial property values fell 10 percent since 2007 to $55.7 billion this year. Some experts say commercial and industrial values could fall more because of a sluggish economy and a large number of property owners who are appealing tax assessments.

And the figures could change. The Michigan Tax Tribunal, a state administrative tax court that decides assessment disputes, has 14,326 pending cases. The number of pending appeals has more than doubled from 6,146 cases in 2000.

And the figures could change. The Michigan Tax Tribunal, a state administrative tax court that decides assessment disputes, has 14,326 pending cases. The number of pending appeals has more than doubled from 6,146 cases in 2000.

Among those backlogged cases are appeals from some of the largest taxpayers in Michigan, including General Motors and Ford.

If there’s a bright side to lower property values, experts say it might be that cheap property could attract new businesses looking for lower real estate costs.

Michigan has had some of the largest home foreclosure rates in the nation. And the 2009 bankruptcies of General Motors and Chrysler wiped out hundreds of small suppliers, leaving their buildings vacant.

Could Michigan become a value play over the next decade for businesses, especially manufacturing companies looking for lower property costs and skilled workers?

“Absolutely,” Tait of SEMCOG said. “Property values went down in most state, but we went down more than others.”

Michigan could be particularly attractive to corporate CEOs -- the investment decision-makers -- because of the relatively low cost of high-end homes and other amenities, according to Tait.

“When you look at economic attracters for us in long run, affordability housing, abundance of fresh water and work force skills, I’m very optimistic,” he said.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!