One man’s appetite for snacks leads to growing Northern Michigan firm

Ed Girrbach likes potato chips.

So much so, he’s put money, determination and business acumen toward a made-in-Michigan venture that is frying 20,000 pounds of raw potatoes a week in the hills outside of Traverse City.

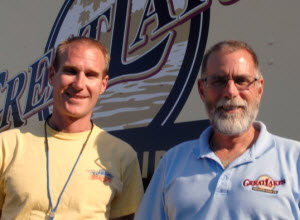

The Great Lakes Potato Chip Co., co-owned by Ed, 63, and son Chris, 33, has gone from a conversation between two pizza restaurant owners to a new entrant to Michigan snack food shelves – a move aided by consumer appetite for locally made products and retailer interest in feeding that demand.

“If it wasn’t for buy local, made in Michigan, we wouldn’t be here talking today,” said President Ed Girrbach during an interview at the company’s plant, housed in a nondescript building tucked off M-72. “There’s no way we ever would have gotten into Kroger, Spartan, Meijer, Wal-mart, if we weren’t made in Michigan. It’s been amazing how many doors that has opened up, and how strong that drive is.”

At first, potato-chip manufacturing was just an idea that emerged in looking at opportunities beyond the family-owned Pangea’s Pizza Pub in downtown Traverse City. Ideas like franchising Pangea’s and manufacturing frozen pizza were explored first and discarded. At one point during the brainstorming, Girrbach said, his son asked: “‘Dad, what do you like?’ I said, ‘Besides pizza, I really like potato chips.’ I said, Let’s do potato chips.’”

They made contact with equipment companies that make fryers, packers and other necessary elements; met with food brokers to discuss distribution; and traveled to other states to talk to owners of potato-chip plants and tour facilities.

“So we kind of had a good idea of what it would take financially, and manpower-wise, to get it going,” Girrbach said.

He said the duo saw market opportunity for a Northern Michigan chip manufacturer, and knew that buy-local interest was big, from attending food shows and operating their restaurant.

Mike DiBernardo, economic development specialist at the Michigan Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, agreed that companies may find easier entry for their products because of buy Michigan/buy local interest.

“I do believe that’s an opportunity for those entrepreneurs,” he said.

A U.S. Small Business Administration loan and personal funds helped finance start-up costs. Within 10 months from concept, the venture produced its first chip, made from potatoes grown in Mecosta County.

Along the way, one contact Girrbach tapped was the Michigan State University Product Center.

Established in 2003 to improve opportunities in Michigan’s agriculture, food and bioeconomy sectors and help new and existing businesses access some of MSU’s expertise, the center assists entrepreneurs in developing and commercializing products and businesses.

“We really are a manager of the client, from start to finish,” said Matt Birbeck, project manager. “Being an entrepreneur is a cold, lonely world. And I think one of the things that we do, is we take clients seriously.”

Still, there have been challenges.

“If there’s one area that we probably didn’t do enough due diligence on, it’s distribution,” he said. “And it’s consumed more of our time than we initially thought. Because we basically had to create a sales team, which is us, and we’re spending a lot of our time on the road, working with distributors, working with stores, doing shows, things like that, just making sure the product is taken care of properly.”

In addition, the MSU Product Center’s Birbeck said potato chips are a “very difficult market to capture,” given the national brands that have far bigger supermarket aisle play and more marketing power and money.

Great Lakes recently had its chips authorized for sale and distribution in University of Michigan food service operations and on-campus convenience stores. That’s an example of “thinking outside the box,” Birbeck said, and “a very good move.”

From its May 2010 start with two part-time employees and Ed and Chris – with the father and son, among other things, loading a crate in the back of Chris’ pickup truck to drive to Mecosta and get in line with semis for potatoes -- the company has grown to nine full-timers, plus the co-owners.

In Michigan, the company’s chips are sold in about 100 corporate-owned Spartan stores, a little over 100 Kroger stores, 66 ACO Hardware stores, 10 Meijer stores and four Whole Foods Market stores. They been cleared for sale in Wal-mart’s Traverse City store, with other Wal-mart store approvals pending in the Detroit area.

Girrbach said sales were $225,000 in 2011, the company’s first full year of operation, and he expects this year to post $600,000 to $650,000 in sales and reach $1.2 million in 2013.

New products on the horizon include a family size bag of chips and a salsa that will augment the company’s tortilla chips on supermarket shelves. Pretzels are also a possibility.

And Girrbach’s advice to other entrepreneurs?

“Get your feet on the street,” he said. “It’s amazing how many people will help you.”

Amy Lane is a former reporter for Crain's Detroit Business, where she covered utilities, state government and state business for many years.

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!