Trump’s tax audit and his bid for a Detroit casino

In recent visits to Michigan, Donald Trump has vowed to restore Detroit’s economy and tirelessly work to provide jobs for young, unemployed African-American residents of Detroit, while also cutting taxes.

“I will produce for inner cities and I will produce for the African Americans,” Trump said at one event, blaming Detroit’s long decline on decades of Democratic rule. “What do you have to lose by trying something new like Trump?”

Possibly a lot, if the reality behind similarly brash promises he made in Detroit 20 years ago are an indicator.

Back in 1997, Donald Trump’s New York-based company, Trump Hotels and Casino Resorts Inc., was one of 11 groups that sought a casino license after Michigan voters approved a proposal a year earlier that allowed for as many as three casinos in Detroit.

Then, as in his presidential campaign, Trump made ambitious claims about what his business acumen and financial investments could do for Detroit -- promising hundreds of jobs for Detroiters, a showstopping hotel and casino, and millions of dollars to tear down vacant buildings.

But Trump’s casino pitch was ultimately brought down by some of the same issues that critics say hinder his presidential campaign today: a lack of tangible evidence to support his bold plans and, as Bridge learned, Trump’s reluctance to produce tax returns.

‘A magnificent casino’

“We look forward to doing a really spectacular job in Detroit,” Trump vowed in June 1997 as he entered the fray for a casino license. “We think it’s going to be a terrific place, a magnificent casino and, if we’re chosen, we will not disappoint.”

Trump proposed an 800-room casino hotel and related amenities employing 6,500 people, the most jobs of any bidders. He also signed an agreement to fund a large expansion of the Motown Museum and said he would spend $14 million to tear down abandoned buildings. Both offers were contingent on Trump getting a casino license.

His development plan was highly popular with Detroit residents, who saw Trump as a larger-than-life celebrity who could bring some glamour to a drab city. Detroiters favored Trump’s casino plan over all others in a November 1997 EPIC/MRA poll of 1,000 city residents, the Detroit Free Press reported at the time.

Trump’s bid was among the seven finalists, but he ultimately failed to win a license. Records reviewed by Bridge show he was undone, in large part, because his casino company was on the brink of financial collapse, according to a Las Vegas accounting firm hired by the city of Detroit to evaluate the finalists’ proposals.

A November 1997 analysis by Nelson Malley & Thorne found Trump’s company had $1.7 billion in long-term debt, was “significantly over-leveraged”-- meaning it was having trouble making interest payments on its debt -- and losing tens of millions of dollars a year.

“The company’s ability to continue to operate under its current capital structure is questionable,” the accounting firm wrote, and Trump’s sources of capital for his required 20 percent equity contribution “not readily identifiable from the proposal.” Financing for the proposed $542 million Detroit casino was dependent on a successful $400-million, junk-bond offering.

The accounting firm concluded that plan by Trump and another bidder, Detroit businessman Don Barden, were the weakest financially of the seven.

Nelson Malley & Thorne’s analysis was buttressed by the views of a financial expert who testified against Trump in a legal dispute involving Trump’s bid to build another casino in Florida at roughly the same time Trump was seeking a casino license in Detroit.

John Finnerty, a finance professor at Fordham University, said in a 2010 affidavit obtained by Bridge that Trump’s casino development company was “financially incapable of serving as the developer and manager” of the proposed Florida project back in 1996.

And Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts Holdings, the company that operated Trump casinos in Atlantic City, N.J. and Gary, Ind. on behalf of Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts Inc., faced a high likelihood of declaring bankruptcy by 2000, Finnerty concluded, due to the weakened state of the parent company.

Trump filed six bankruptcies in his former hotel-and-casino empire, including a 2004 filing by Trump Hotels & Casino Resorts, which owned the Atlantic City and Gary casinos.

Checks and tax returns

Bob Berg, a Detroit public relations executive who represented Trump in his bid for a Detroit casino, said he doesn’t recall financial problems being much of an issue as Trump dazzled Detroiters with his plans to help revitalize the struggling city.

During Trump’s presidential campaign, there have been numerous reports of Trump not paying his contractors and suppliers. But Berg said he was always paid for his public relations work by Trump’s organization.

“Their checks always cleared,” he said, chuckling.

Most of the those seeking a casino license enlisted well-known local businesspeople as partners in an attempt win favor with the city. Trump teamed up with Mel Farr, a former Detroit Lions star who later became one of the largest African-American auto dealers in the country.

Farr, who had a 5 percent ownership interest in Trump’s casino proposal, saw his auto dealership empire collapse after defaulting on $50 million in debt owed to Ford Motor Credit Co. in the early 2000s, according to Automotive News. He died in 2015.

The Nelson Malley & Thorne analysis said neither Farr nor his entertainment company had “any experience or exposure relevant to the (Detroit) casino project,” suggesting Farr’s role was minimal.

C. Beth DunCombe, who chaired Detroit’s casino advisory committee at the time of Trump’s casino pitch, said Trump’s problems went beyond company debt.

Trump, she said, was the only bidder who refused to release tax returns, which the city required. She said he claimed he couldn’t release them because they were being audited -- the same reason he has given for not releasing them now as a candidate for president.

“That really stood out,” DunCombe said. She couldn’t remember if the city had asked for his personal or his corporate tax returns, but said his failure to release them was a major reason Trump’s bid was not among those recommended to then-Detroit Mayor Dennis Archer, DunCombe’s brother-in-law.

Mayor Archer picked the winners, subject to approval by state gaming regulators. The winning bids, announced in November 1997, came from Atwater Casino Group (which later became Motor City Casino), Greektown Casino Group and MGM Grand.

Seen better days

DunCombe said her team learned a lot about the bidders as committee members traveled around the country investigated their properties.

They first stayed at Trump’s Taj Mahal casino hotel in Atlantic City. DunCombe said the property was so shabby she wondered if the city had made a mistake in embracing the casino industry. The carpets were worn and there were cigarette burns in the furniture.

“It looked like it really needed to be spruced up,” she said. “There was a lot of deferred maintenance. I was really discouraged that we were going to have gaming here. It didn’t feel good.”

In 1991, Trump had declared bankruptcy for the Taj Mahal, which he once called “the eighth wonder of the world.” He later sold the property and, as it happens, the casino was finally closed by its owners this month.

It’s impossible to know if a Trump casino would have succeeded in Detroit had he been granted one of the three licenses. Berg said he thinks he would have, saying the city’s three casinos “are still going strong. I can’t think of any reason why he wouldn’t have been successful.”

And Trump clearly believes today that once in the White House, he can deliver economic improvement to African-American communities like Detroit. During an appearance in rural Dimondale, near Lansing, Trump bragged that he would become so popular with African Americans that, by the end of four years in office, he would capture 95 percent of their votes.

It is a bond the GOP nominee sought to strengthen in a much-publicized appearance at a Detroit church in early September, and through his pledges to expand school choice, cut taxes, make Detroit and other cities safe, and end racial and political devisiveness.

But Detroiters, once enamored of the celebrity businessman, have cooled considerably.

A statewide WDIV/Detroit News poll taken at the end of September found zero support for Trump in Detroit, although only 39 city voters were polled. That’s in line with an NBC News/Wall Street Journal/ Marist poll this past summer which found zero support for Trump among African American voters in Ohio and Pennsylvania as well.

DunCombe said Michigan developed one of the toughest casino regulatory structures in the country, which would have forced Trump or any other bidder to perform or lose their license. A Trump casino failure would have jeopardized thousands of jobs, 66 percent of which he had said would go to Detroiters.

“If he had been granted a license, he would have done things right,” she said. “If he had done things wrong, he wouldn’t have had a casino.”

Business Watch

Covering the intersection of business and policy, and informing Michigan employers and workers on the long road back from coronavirus.

- About Business Watch

- Subscribe

- Share tips and questions with Bridge Business Editor Paula Gardner

Thanks to our Business Watch sponsors.

Support Bridge's nonprofit civic journalism. Donate today.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

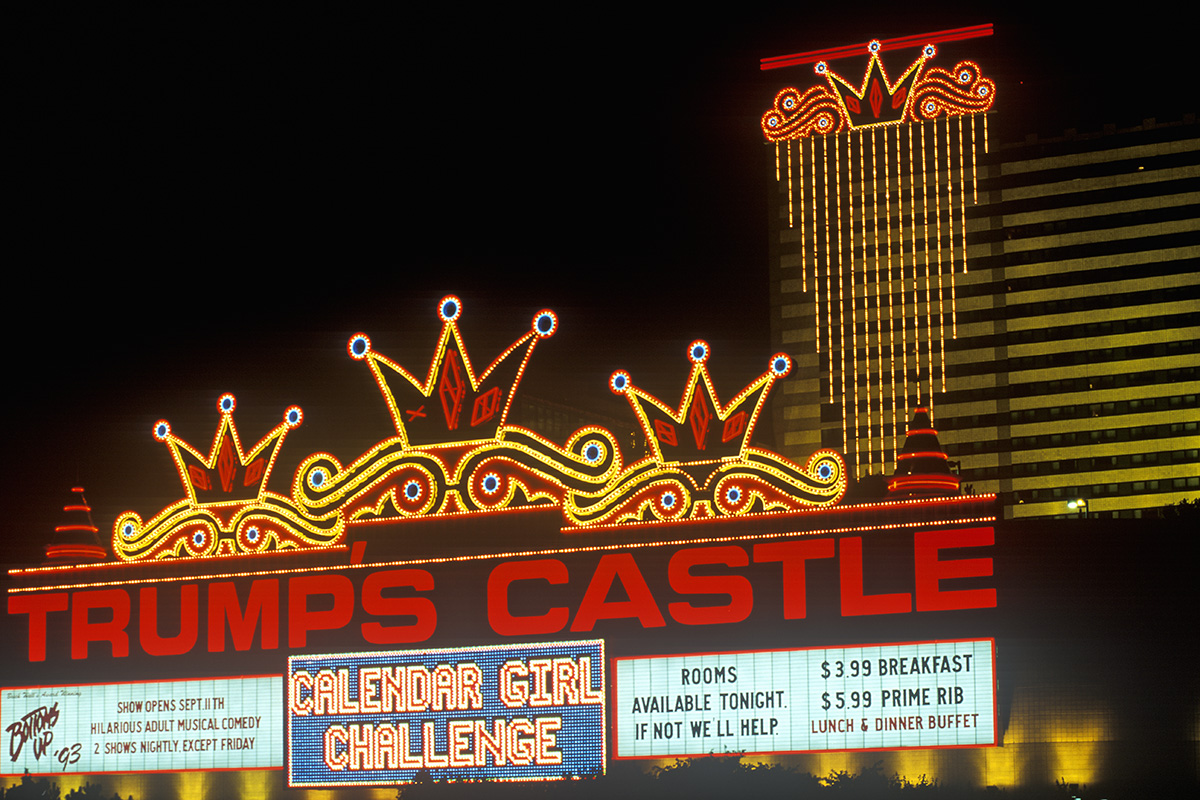

Donald Trump promised a glitzy casino hotel, an expansion of the Motown Museum and millions of dollars to demolish abandoned buildings if his 1997 bid for a Detroit casino was accepted. (courtesy photo)

Donald Trump promised a glitzy casino hotel, an expansion of the Motown Museum and millions of dollars to demolish abandoned buildings if his 1997 bid for a Detroit casino was accepted. (courtesy photo) Bob Berg, a veteran public relations specialists, represented Donald Trump’s company in its bid to win a casino license in Detroit. He said he didn’t recall that Trump’s finances were a problem for the businessman. (Courtesy photo)

Bob Berg, a veteran public relations specialists, represented Donald Trump’s company in its bid to win a casino license in Detroit. He said he didn’t recall that Trump’s finances were a problem for the businessman. (Courtesy photo) C. Beth DunCombe, who chaired Detroit’s casino advisory committee at the time of Trump’s casino pitch, recalled the developer’s aversion to sharing tax returns. (Courtesy photo)

C. Beth DunCombe, who chaired Detroit’s casino advisory committee at the time of Trump’s casino pitch, recalled the developer’s aversion to sharing tax returns. (Courtesy photo)