In Flint, questions about Legionnaires’ death toll

Short of breath, and suffering from chest pains, Bertie Marble was heading back to the hospital last year. “I don’t know what’s wrong,” she told her oldest daughter on her way to McLaren Regional Medical Center in Flint.

It would be the second trip to McLaren in a week for the 68-year-old dialysis patient. Two days later, on March 11, Marble developed a fever and was placed on antibiotics to fight an undetermined infection. Days after that, another diagnosis: “healthcare associated pneumonia.”

During this second hospital stay, which lasted 11 days, Marble’s heart stopped. Twice.

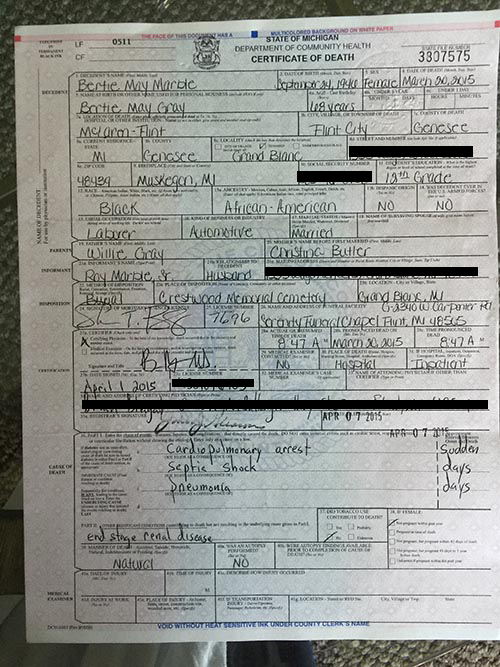

Marble, the mother and grandmother to two legendary Flint-area basketball stars, died on March 20, 2015. Her death certificate lists cardiac arrest brought on by septic shock due to pneumonia.

However, deep in her medical file, twice-mentioned is a word that never appears on her death certificate. It’s a word that, much like lead, has come to haunt Flint.

“Legionella.”

The quietest of outbreaks

At the time of Marble’s hospital visits, McLaren officials had known since the previous August ‒ a period of roughly seven months ‒ that legionella bacteria, which can cause a more severe form of pneumonia, had found its way into the hospital’s water system.

See the complete Legionnaires’ disease timeline

Months before that, in spring 2014, McLaren had recorded an uptick in Legionnaires’ patients, which experts say was likely caused by the city’s disastrous switch to Flint River water.

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention urges hospitals where the legionella bacteria is found to test patients who are most vulnerable to the disease, such as the elderly, particularly those with weakened immune systems from conditions such as diabetes or kidney disease; patients like Marble, in other words.

But Marble’s medical records, which the family shared with Bridge, indicate that staff did not attempt a test her for Legionnaires’ until well into her second admission, days before she died, at which point Marble was unable to provide urine.

In the course of both stays in March 2015, neither Marble nor the adult children who doted on her were informed the hospital was dealing with Legionnaires’ disease, family members told Bridge. Had they known, they say, they would have steered their medically frail mother to another hospital. Had they known, they would have wanted her tested early for Legionnaires’ instead of when she was near death.

“Why didn’t they tell us they had legionella in their hospital and they were testing her for it?” said Jeron Marble, youngest son of Bertie Marble. “It’s more than 12 people who died from this, without a doubt. How many other people are out there? Nobody wants to touch that. And it hurts me because I know my mother is one of them.”

As it happened, Bertie Marble’s death dovetailed with a trio of health woes that were pummeling Genesee County in early 2015, though nobody in government thought to let residents know at the time: There was the lead entering Flint’s drinking water, silently exposing thousands of children to the toxin. There was a Legionnaires’ outbreak that would kill at least 12 people and sicken scores of others. And, we now know, there was a recent 60 percent rise in county deaths attributed to pneumonia or the flu.

More than a year later, Marble’s treatment raises questions about McLaren’s handling of the legionella outbreak and the hospital’s transparency with patients and their families. Her story also raises broader questions about whether other patients, at McLaren or elsewhere, may have fallen ill or died from Legionnaires’ without being diagnosed. Experts say it’s possible that the spike in recorded pneumonia and flu deaths may have also included some victims of Legionnaires’.

A lawyer for the family and independant healthcare experts said it’s unclear how many other people fell ill or died from Legionnaires’ ‒ whose symptoms mimic more common forms of pneumonia ‒ because neither McLaren nor government health officials alerted the general public to the disease outbreak for more than a year.

“The family was kept in the dark by the hospital, which had much more information and knowledge,” said William Goodman, a civil rights lawyer, who said he is preparing a lawsuit on behalf of the Marble family.

Numbers in question

McLaren already faces litigation from others said to have contracted Legionnaires’ while in the hospital’s care, including one who died. That suit, brought by personal injury lawyer Geoffrey Fieger against the hospital, the state and others, argues that McLaren failed in its legal duty to inform patients of the threat posed by Legionnaires’.

One patient in the lawsuit, Connie Taylor, who nearly died of kidney failure after falling ill, told the New York Times she left the hospital without ever being told she had Legionnaires’. She only found out, she said, this past January after she requested a copy of her medical records after Gov. Rick Snyder belatedly announced the existence of a Legionnaires’ disease outbreak.

Officially, 91 people contracted Legionnaires’ in Genesee County in 2014 and 2015, including the 12 who died, according to state and county health records. The diagnoses began to flow in shortly after the state ordered Flint to switch its source of drinking water from the Detroit system to the Flint River without properly treating the water in April 2014. Though it cannot be definitively proven, water and health officials generally agree the water switch also spawned the Legionnaires’ outbreak.

How many others, like Marble, may have contracted Legionnaires’ without ever being diagnosed? There is likely no way to know for sure.

What is known, however, is that in 2014 Genesee County recorded a 64-percent spike in deaths attributed to pneumonia or flu over the previous year. The 92 deaths in 2014 were far higher than the 56 identified in 2013.

Experts say without aggressive testing of patients at higher risk of Legionnaires’, it would be easy to mistake Legionnaires’ cases for ordinary pneumonia, and that likely happened in Flint.

“When studies have been done of community-acquired Legionnaires’ disease, the conclusion is only a small proportion are actually diagnosed,” said microbiologist Janet Stout, a pioneer in Legionnaires’ research who McLaren hired after detecting legionella in its water.

“By extension, it’s logical to assume there are some cases that may have been missed. It’s certainly possible there were more cases” in Flint.

McLaren officials declined to be interviewed about the Legionnaires’ outbreak, despite repeated requests from Bridge. Nor would they discuss Bertie Marble’s treatment or her medical records, citing patient privacy laws.

In January, it was the state, not McLaren, that revealed the hospital found legionella bacteria in its water system in 2014. Only then did McLaren publicly acknowledge that exposure, while emphasizing the safety of its water. What has not been reported, until now, is that a state health report released this spring indicates that McLaren also found environmental samples in August 2015 that “tested positive for Legionella.”

Without discussing specifics, Laurie Prochazka, a McLaren spokesperson, told Bridge in an email the hospital “has consistently followed all statutory regulations and notification requirements. I would also like to stress that McLaren Flint is diligent in our water quality monitoring, and regular testing shows the water at McLaren Flint meets safety and quality standards.”

Despite requests from Bridge, county and state health officials have provided few details about the spike in recorded pneumonia and flu deaths in Genesee County in 2014, a period that overlapped with the Legionnaires’ outbreak.

They would not release records on pneumonia and flu deaths in Genesee County for 2015, saying that data is not yet compiled. Nor would officials provide a breakdown of how many of the 2014 deaths were attributed to pneumonia versus the flu. Finally, officials would not disclose how many of the 12 confirmed Legionnaires’ deaths in Genesee County since 2014 could be traced to patients at McLaren.

A vulnerable patient

Because Legionnaires’ had been found in McLaren’s water system only months earlier, Bertie Marble, elderly and medically frail, appeared to fit the CDC’s profile of the type of patient most at risk of acquiring Legionnaires’ disease, and thus a prime candidate for testing.

Early detection of Legionnaires’ improves chances of recovery and means the patient can be treated with a class of antibiotics that may differ from than the ones used to treat more common forms of pneumonia.

Bertie Marble’s children say they wish the hospital would have tested their mother early for the disease, and say they feel betrayed by the hospital’s silence.

“We deserve to know what happened,” said LaShema Marble, the youngest daughter.

According to Goodman, the family’s attorney, McLaren was too slow to screen Marble for Legionnaires when she was still healthy enough to supply a urine sample. More provocatively, he intimates that hospital officials may have been driven by a reluctance to know whether Marble acquired the disease at McLaren.

“They were trying to conceal the spike in Legionnaires’ and pneumonia,” he told Bridge.

Goodman also invoked a conclusion by a state-appointed task force investigating the Flint water crisis, which found that “environmental injustice” played a role in the state’s slow response to the complaints of a majority-African-American city.

So too, Goodman said, official silence about Legionnaires infringed on the civil rights of Genesee County residents like Marble. “It’s clearly racial discrimination against a community that’s predominantly African American,” he said.

Finding a link

Legionnaires’ disease is a severe form of pneumonia that typically develops from inhaling water droplets containing legionella bacteria. Low levels of legionella are not unusual in building water systems, but the bacteria can multiply and colonize when it is warmed in distribution systems of larger facilities, such as hotels or hospitals.

Legionnaires’ is fatal in about 10 percent of cases, according to the CDC. Fifty of the 91 people who contracted Legionnaires’ disease in Genesee County over a 17-month period in 2014 and 2015 had been at McLaren, according to state data. The 91 cases marked a huge increase for Genesee, which averaged fewer than 10 Legionnaires’ illnesses over the previous four years.

But state and county health officials say they are not prepared to say how many, if any, of the 2014 deaths classified broadly as pneumonia may have involved Legionnaires.

“Pneumonia can have many causes; these data do not tell us what caused the pneumonia for all of these deaths. There are likely to be many causes,” Jennifer Eisner, a spokesperson for MDHHS, wrote in an email. “In order to put this into context and provide a full, accurate picture, our epidemiologists need more time to review data going back several years.”

Asked whether Genesee County’s increase in 2014 pneumonia and flu-related deaths may be tied to the water crisis, Suzanne Cupal, public health supervisor for the county, said “there are many probable reasons including increased testing.”

“When you are specifically concerned about one type of pneumonia and are doing increased testing for pneumonia, you will find it,” she said in an email to Bridge. “Each year is different. Yes, it is a concern and yes we monitor it.”

Marble goes to McLaren

Bertie Marble, mother of four, grandmother of 11, lived with her husband, Roy Marble, Sr. in a stately colonial in Grand Blanc, about eight miles southeast of Flint. The Marbles moved to Grand Blanc after her son Roy, Jr. was drafted into the NBA and bought her a house in 1989. The home was not on the Flint water system.

She was, by all accounts, in poor health before her first trip to McLaren. In the years before her death, Marble struggled with renal failure and began dialysis treatment. In August 2014, the same month legionella was first detected in McLaren’s drinking water, Roy, Jr. was diagnosed with cancer. For a time, Bertie Marble moved her dialysis treatment to Iowa City, Iowa to be near her son.

Bertie Marble’s two youngest, LaShema and Jeron, were a match to donate a kidney to her, but doctors said her high blood pressure needed to improve before she could get the operation, her family said.

When Bertie Marble came down with shortness of breath and chest pains on March 2, 2015 it was LaShema who took her to McLaren. “She wouldn’t go anywhere else. She would stick to McLaren,” the daughter said.

Marble underwent a battery of tests, was given medications and discharged on March 6.

But three days after returning home, Jeron called to check on her and couldn’t make out what she was trying to say.

“Her conversation was all over the place. I say, ‘Ma, do you understand what I’m saying?’ And there’s long pauses. I say, ‘Hello? Are you there?’” Jeron recalled recently as he sat in his parents’ living room.

Confusion, according to Stout, the Legionnaires’ expert, can be a symptom of Legionnaires’ in older patients who typically do not exhibit a fever early on.

Theresa, Bertie’s oldest daughter, decided to take her mother to urgent care. Her mom didn’t want to return to the hospital, but relented. Even though she wasn’t feeling her best, Bertie Marble was not the type to be caught in public looking haggard. After getting dressed, she put on her favorite black wig and a leather coat.

Bertie Marble stumbled and fell before leaving the bedroom, daughter Theresa said.

The urgent care clinic determined Marble was too sick for their doctors. They called an ambulance to take her to McLaren’s emergency room.

It was March 9, 2015, and from the moment Bertie Marble arrived at McLaren she presented at least three of the seven health risk factors for Legionnaires’, according to the CDC. She had renal failure. At 68, she was well over 50 years old. And she had diabetes.

Marble was given a chest X-ray, which revealed a small amount of fluid around her left lung which, together with chest pains and shortness of breath, can be a symptom of pneumonia and, in its more virulent form, Legionnaires’.

There was another factor weighing in favor of testing Marble for Legionnaires’: Her previous admission at McLaren, a place where others were treated for Legionnaires’ and where the bacteria previously was found in the water.

The suggested test for Legionnaires’ is a combination of urine analysis and a lower respiratory tract culture, which are supposed to be given before a patient is put on antibiotics. Records indicate, however, that efforts to test for Legionnaires’ were not taken until well after Marble was given antibiotics and her condition had deteriorated.

On the third day of her second stint at McLaren, March 11, Bertie Marble developed a fever. By March 13, with the fever continuing, an infectious disease consultation was requested. Sepsis, a potentially life-threatening complication from infection, was suspected and she was placed on antibiotics, her medical file shows.

“The entire time, we asked what was wrong with our mom,” LaShema said. “Unknown infection, that’s what they called it. Unknown infection.”

Bertie Marble rallied a bit on March 15 and in a moment of alertness told her children she loved them. Soon after that she said, ‘Where my baby Bug at?’,” referring to Roy Jr., her son with cancer. Those would be her last words, her daughter Theresa said. By that evening, “health-care associated pneumonia” was written into her chart, a term that indicates a patient developed the infection after a recent hospital visit.

She was prescribed Levaquin, an antibiotic used to treat bacterial infections, including Legionnaires’ disease.

By then, Marble had most of the six symptoms the CDC says warrant testing for Legionnaires: Severe pneumonia, a weakened immune system, she was in a facility that had a connection with Legionnaires’, and she was suspected of having healthcare-associated pneumonia.

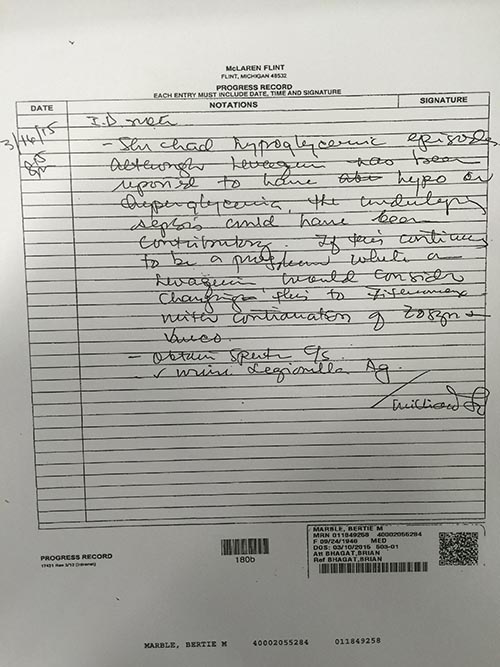

The next morning, March 16, Bertie Marble’s heart stopped twice. Medical staff revived her. That night, at 8:55 p.m., a doctor requested she be tested for legionella, her records show.

But it was too late. On March 17, medical records show Bertie Marble was unable to produce urine for an analysis. The records also reference a throat culture, or sputum test, shortly before Marble died. Those results do not mention legionella, but a negative or inconclusive sputum culture cannot rule out a Legionnaires’ diagnosis because the test is inadequate as a sole diagnostic test.

Legionnaires’ breaks out

Two months after Bertie Marble died, the Michigan Department of Health and Human Services determined that from June 6, 2014 to March 9, 2015, 45 people came down with Legionnaires’ disease in Genesee County, with seven dying. Prematurely, state health officials quietly pronounced, “The outbreak is over,” on May 29, 2015, records show.

The state was wrong.

In its latest report this past April, MDHHS said the Legionnaires’ disease investigation was “on-going” and updated the death toll to include people not previously counted.

Despite the presumed link between the April 2014 Flint water switch and the uptick in Legionnaires’ cases two months later, neither the state, nor independent experts, say they have definitive proof that the Legionnaires’ outbreak and deaths are related to the water crisis.

The Michigan Department of Health and Human Services “cannot conclude that the increase is related to the water switch in Flint nor can we rule out a possible association at this time,” according to the health department’s news release dated April 11.

Dr. Mona Hanna-Attisha, the pediatrician at Hurley Medical Center who led the research project that revealed dangerously elevated lead levels in Flint children, said as far as she knows there have not been any discussions about the spike in pneumonia-related deaths within the Flint Water Interagency Coordinating Committee the governor appointed her to.

But she told Bridge she sympathized with families like the Marbles.

“Families want truth. We’re very much going through a truth and reconciliation process in Flint,” she said. “Families want accountability. They want to know what happened, the who-what-when so they can start the hard process of healing.”

Marc Edwards, the Virginia Tech professor who helped confirm high lead levels in Flint’s drinking water, said he would not be surprised if the huge spike in 2014 pneumonia and flu deaths in Genesee included undiagnosed cases of Legionnaires’.

“Legionella certainly causes pneumonia, and underdiagnosis and under-reporting is a well-known issue, not just in Michigan but nationwide,” Edwards said in an email. “Also, because legionella is the only opportunistic premise plumbing pathogen disease that is reported, it is quite possible that other sicknesses occurred as a result of the lack of corrosion control” in Flint’s water supply.

Living with uncertainty

On March 20 of last year, McLaren medical staff called Bertie Marble’s family to her bedside. She was hooked up to a machine that offered continuous, 24-hour dialysis. She was on a ventilator.

“I had grabbed her hand and I had my own answers,” her husband Roy Marble, Sr., recalled. “She’d been gone.”

Bertie Marble was pronounced dead at 8:47 p.m.

Ten months would follow before Gov. Rick Snyder announced the Genesee County Legionnaires’ outbreak to a stunned and angry public.

“If we would’ve known there was an [Legionnaires’] outbreak in the area, in Flint, in McLaren, my mother could’ve been taken to Genesys (Health System in Grand Blanc) or University of Michigan in Ann Arbor,” said Jeron Marble, the youngest child. “She had four kids willing and able to get her to these place as needed.

“That’s what hurts so much,” he said. “We weren’t given a choice. That decision was made for us when they didn’t tell us what was going on. They chose their business over alerting the public.”

Stout, the expert, said lung tissue can be tested for the disease in an autopsy taken soon after someone dies. But she said exhuming someone’s body long after they die to test for the bacteria is not likely to yield results.

“At this late date,” researcher Marc Edwards added, “we can only build very strong circumstantial cases.”

After Bertie Marble’s death, Roy Marble, Jr., the former basketball star, also declined. It was as if someone pulled his legs from beneath him, his sister said. In a matter of a few months, the 6’6’’ Roy Jr. went from walking on a cane to using a walker to relying on a wheelchair. He died last September, six months after his mother.

The family says it recognizes that Bertie Marble had serious health issues prior to the Flint water crisis. Still, they say they wonder whether she, and others, would have lived longer had Flint’s water been kept safe.

With that in mind, the Marbles said they want health officials to investigate every death attributed to pneumonia during the water crisis for signs of Legionnaires’. To not do so, shows disregard for people who may have been exposed to a life threatening disease, Jeron Marble said.

“It’s unfair to other people’s loved ones. It’s not just about us,” he said. “They got some explaining to do.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Bertie Marble died March 20, 2015 during her second admission at McLaren Regional Medical Center in Flint. Her medical records list healthcare-associated pneumonia.

Bertie Marble died March 20, 2015 during her second admission at McLaren Regional Medical Center in Flint. Her medical records list healthcare-associated pneumonia. Bertie Marble’s death certificate says she died from cardiac arrest caused by septic shock due to pneumonia. Her medical files show she also had some symptoms that are also found in victims of Legionnaires’ disease

Bertie Marble’s death certificate says she died from cardiac arrest caused by septic shock due to pneumonia. Her medical files show she also had some symptoms that are also found in victims of Legionnaires’ disease Janet Stout, a pioneer in Legionnaires’ disease research and associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh, was hired as a consultant to assess the situation at McLaren hospital in Flint during the Legionnaires’ disease outbreak. She said the outbreak that killed 12 people is almost certainly connected to the Flint water crisis and that it is likely more people contracted the disease than the 91 confirmed cases.

Janet Stout, a pioneer in Legionnaires’ disease research and associate professor at the University of Pittsburgh, was hired as a consultant to assess the situation at McLaren hospital in Flint during the Legionnaires’ disease outbreak. She said the outbreak that killed 12 people is almost certainly connected to the Flint water crisis and that it is likely more people contracted the disease than the 91 confirmed cases. Bertie Marble’s medical file references legionella bacteria at least twice: on March 16, 2015 when a doctor requests a urine test for it and the next day when it is determined that she is no longer producing urine that is needed for the testing

Bertie Marble’s medical file references legionella bacteria at least twice: on March 16, 2015 when a doctor requests a urine test for it and the next day when it is determined that she is no longer producing urine that is needed for the testing