Racial divide persists in Michigan's infant mortality rate

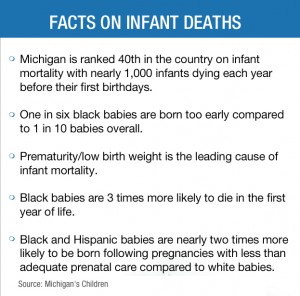

For nearly 30 years, Michigan has been reducing its infant mortality rate. Still, as of 2009, a black infant in Michigan is three times more likely to die than a white baby, according to the latest statistics from 2009.

In fact, the mortality rate for black infants in Michigan for 2009 (15.5 per 1,000 live births) is roughly the same today as for white infants in 1973 (15.2). In the last decade, infant mortality rates for white infants have decreased from 5.9 to 5.4.

“We’re glad that our infant mortality rates have gone down, but we are still ranked 40th in the nation, which is nothing to be proud of,” said Jack Kresnak, president and CEO of Michigan’s Children, a nonprofit advocacy group for children and families. “We have a serious issue here. Babies of color are not seeing their first birthdays."

Since 1973, the infant mortality rate for black infants in Michigan has been cut by about half. In the same period, infant mortality rates for whites have gone down by about two-thirds. The statewide infant death rate in 2009 was 7.5 deaths per 1,000 births. Michigan suffered 881 infant deaths out of 117,309 live births that year, according to figures from the Michigan Department of Community Health.

Michigan's rate was above the 2009 national average of 6.42 per 1,000 reported by the federal Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Michigan's racial disparity also was larger than found nationally, with the black infant death rate of 12.71 about 2.5 times as high as the national white rate of 5.32.

While the state of Michigan does not calculate rates in counties with fewer than six infant deaths, mortality rates varied a great deal across Michigan. The highest county rates were found in Lapeer (13.0), St. Joseph (11.9), Calhoun (11.7), Saginaw (10.7) and Wayne (10.1). (County-by-county mortality figures)

While the state of Michigan does not calculate rates in counties with fewer than six infant deaths, mortality rates varied a great deal across Michigan. The highest county rates were found in Lapeer (13.0), St. Joseph (11.9), Calhoun (11.7), Saginaw (10.7) and Wayne (10.1). (County-by-county mortality figures)

Overall infant mortality has decreased because of medical technology improvements, SIDS-prevention education, improving women’s health before they become pregnant, and increasing access to health care.

Premature births and low birth weight are the leading causes of infant mortality, and factors affecting low-income women are contributors to them.

When he raises the topic at the State Capitol, legislators often believe that the government should not be sticking its nose into the family's business, Kresnak explained.

“But women living in poverty face difficult choices considering the context of available resources within families, neighborhoods and communities,” he said. “Pregnant women and infants of all races often face issues of domestic violence, substance abuse, second-hand smoke, household pests that spread bacteria and disease, and contamination of air, water and ground.”

“There are a lot of things that can be done that with just a little bit of government help would make a big difference.”

The solution to the racial disparity will come only through investing in public health strategies, said Amy Zaagman, executive director of the Michigan Council for Maternal and Child Health.

Factors affecting the infant mortality rate, she said, include the availability of family planning resources, health status of women pre-conception, access to pre-natal care, stability of relationships and adequate support system for pregnant woman and their new babies, management of chronic health issues during pregnancy, environmental concerns, increasing prevalence of premature birth, proper support for complex medical needs of some newborns, access to good nutrition and promotion of breastfeeding, and education on how preventable accidents including assuring a safe sleep environment for infants.

“In theory, these are the issues you can impact,” she said. “We will never eliminate fatal birth defects or some amount of accidents.”

One reason for the racial discrepancy is the fact that the Medicaid reimbursement rate limits access for many impoverished women to general health care and specialty doctors, including obstetricians, gynecologists and pediatricians, Kresnak said.

Medicaid reimbursements are low enough to deter specialty doctors from taking Medicaid patients, Kresnak said, adding that physicians may already be at their limit of Medicaid patients and can’t afford to care for more.

“Hence we have many women giving birth who haven’t had consistent prenatal care,” he said. “They might find a clinic where you’ll have a general practice doctor, but statistics show so many women just don’t have access to health care.”

A majority (51 percent) of Michigan births were covered by Medicaid in 2010, so access to health care, including the prenatal care essential to reducing low birth weight and infant, saves significant taxpayer dollars.

Teenage pregnancies also are a factor in the discrepancy among races, as women of color are two to three times more likely to be teen moms, and their babies are more likely to be born too soon and too small, studies show.

Gov. Rick Snyder has identified infant mortality as one of 10 key health-care issues facing the state. In September, he called infant mortality a “critical indicator of the overall health and welfare of Michigan and the quality and accessibility of prenatal care for women."

“Infant mortality is deeply traumatic at a personal level,” said Zaagman, “but I’m hopeful that the governor’s focus on the issue will point to how Michigan’s rate speaks to a much larger issue: how we are missing the mark on a number of levels that cannot be addressed by focusing on one medical intervention or one point in the timeline of a pregnancy/infant’s life. We need a multi-faceted approach and it will not be a quick fix.”

Home visitation programs for at-risk families have been proven to help keep families together and the child healthy, safe and on his or her way to an active preschool growth and development, during which time his brain is developed and lifetime habits formed.

Over the next five years, Michigan will receive its share of $1.5 billion in federal funds for the Maternal, Infant and Early Childhood Home Visiting Program. The federal funds will mostly go to grow, enhance and expand current programs operating in Michigan.

The largest home visit program in Michigan is the Maternal Infant Health Program (MIHP), a state Medicaid service available to any pregnant woman or infant up to age 1 eligible for Medicaid.

Under a recent grant via the federal Affordable Care Act, Michigan will develop a system to ensure that all babies have a medical home for preventative and health care.

Kresnak said Michigan residents should hold the governor, his administration and our legislators accountable for reducing infant mortality in a state where nearly eight of 1,000 babies are dying before their first birthday and the health and wellness of black pregnant women and babies is decades behind. Policy-makers need to better understand how improved policies can reduce racial disparities, he added.

“We don’t want to just talk about it,” he said. “We want to see more improvement in the babies of parents of color.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!