Amid opioid crisis, few doctors use Michigan’s outdated drug monitoring tool

The case against Dr. Oscar Linares, once the busiest internist in Monroe, Mich., broke five years ago, but paging through the criminal complaint filed against him in 2011 reveals a parade of startling details that time hasn’t softened.

In just one five-month period in 2010, Linares, working out of his Monroe Pain Clinic, wrote prescriptions for more than 2.6 million legal pain-killing pills with abuse potential, including Oxycontin, Percocet, Vicodin, Opana, all well-known and highly prized by addicts. The complaint described lines of patients stretching from his standing-room-only waiting room (where patients took numbers, as though they were at a delicatessen) outside and down the block. The office had its own staffer to handle congestion in the parking lot. Linares would sometimes see patients via video link between his office and the exam rooms, asking a nurse to hold up the patient’s record to the camera and dispensing prescriptions to the room via vacuum tube.

Patients typically left with prescriptions for generous quantities of the most powerful opiate painkillers on the market; one FBI informant complaining of back pain was, after perfunctory testing, prescribed 60 80mg Oxycontin four months in a row, a maximum-strength dosage typically given only to patients in the most severe pain, or with already well-established drug resistance.

When an employee allegedly told Linares that clinic staff had seen patients selling and exchanging pills in the parking lot, the doctor is said to have replied, “There is nothing I can do; I am not the police.”

Of course, there was a great deal Linares could have done, and that others in the prescription pipeline did do – starting with local pharmacists who began refusing to fill his prescriptions. Not only did the sheer volume send up red flags, they could check his prescribing patterns in the state’s online database of pharmaceutical transactions for commonly abused drugs.

The Michigan Automated Prescription System, or MAPS, is intended to alert registered personnel (commonly prescribers and pharmacists) when a patient has gone to multiple doctors in search of medication, or when doctors like Linares are dispensing troubling amounts of narcotics.

Related: Northern Michigan counties vulnerable to HIV, hepatitis C outbreaks

MAPS went online in 2003, as the nation was awakening to the connection between abuse of legally prescribed opioids and the growing problem of heroin addiction. Helped along with grants from the U.S. Department of Justice, states established their own prescription drug monitoring programs, and today 49 are in place across the nation; only Missouri opts out.

But Michigan’s MAPS system hasn’t been significantly upgraded since 2003, and today the state has fallen behind its neighbors in tracking prescription drug abuse. Critics say the system is slow and frequently balky, so much so that many doctors simply don’t use it; one pharmacist said only 17 percent of prescribing doctors use it routinely, a figure that couldn’t be confirmed. Nationally, the figure is closer to 50 percent, according to one study.

The recently passed state budget provides $2.4 million to upgrade the system, but improvements won’t be functional for another year. Meanwhile, a Senate bill now in committee would require Michigan doctors to check MAPS before prescribing or dispensing one of the drugs it monitors, but only for new patients. By contrast, Ohio requires doctors to check that state’s drug monitoring system before giving opioids to any patient, a tough-love approach that Ohio officials say has made it harder for addicted patients to “doctor shop.”

If and until the less-restrictive Michigan Senate bill passes, use of MAPS remains voluntary for doctors who write prescriptions, according to the state. (Doctors still must report to MAPS drugs given directly to patients, such as by samples.)

The MAPS upgrade didn’t become a legislative priority until it was specifically requested by the Michigan Prescription Drug and Opioid Abuse Task Force, formed last year by Gov. Rick Snyder to research and make recommendations to address legal drug abuse in the state, which made improving MAPS one of its recommendations in its final report last fall.

Tracking prescription drugs is particularly important when patients see multiple prescribing doctors. The Center for Healthcare Research & Transformation at the University of Michigan called uncoordinated prescription opioid use a critical patient safety issue, as accidental overdoses, from both legally prescribed opioids and heroin, have climbed in the state, increasing sixfold, from 81 to 519, between 1999 and 2013. (In 2014, Michigan’s accidental overdose deaths ranked ninth in the nation.) Systems like MAPS provide multiple opportunities for healthcare professionals to raise alarms.

But MAPS has to be used to be effective, and in the 13 years since it came online, usage has dwindled, mainly over performance issues. The existing system is slow, prone to crashes and lacks the capacity to handle all the individuals authorized to use it.

“My colleagues have had a variety of experiences with it,” said Carrie Germain, a managed-care pharmacist with HealthPlus in Flint. “(Reports) come back immediately for some, but for others, there are long delays.” Performance varies according to time of day and demand on the system, which is not predictable by users. And with delays lasting as long as 15 minutes, some stop using it entirely.

Twenty-nine states require prescribers and/or dispensers to check their state drug databases under at least some circumstances, but Michigan is not one of them. Ohio is, as are states in regions hardest-hit by the opioid epidemic, including Kentucky, West Virginia and Tennessee, according to data compiled by the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws.

Rep. Bill LaVoy, D-Monroe, said the Linares case was a wakeup call for his district, and he’s taken an interest in drug-control policy ever since. He has advocated for mandatory MAPS use by prescribers, but said that when he did so, a local doctor “contacted me and told me, ‘If you’re going to mandate this system, you have to see how (badly) it works.’” It was a sobering assessment.

Old problem, new era

The generally accepted narrative of the opioid crisis in the U.S., documented in books and more ephemeral journalism, goes like this: Sometime in the late 20th century, there was a cultural shift in attitudes surrounding pain.

Jack Kevorkian was helping people kill themselves, some of whom complained of chronic pain and saw death as the only possible relief. Doctors began treating pain as the “fifth vital sign,” not just a symptom of an illness or injury, but as a condition to be assessed (and treated) along with temperature and pulse. Even the pain of laboring in childbirth, an experience as old as humanity itself, was no longer required; the use of epidurals tripled between 1981 and 2001, with women asking for it at the hospital admissions desk.

Into this shift stepped a number of pharmaceutical companies, offering powerful new opiate-based painkillers, telling doctors that these drugs were far less addictive than they may have been taught in medical school. Under a doctor’s care, opiates could be safely taken by those suffering from pain with very little risk of addiction -- or so the drugs’ marketers said.

Soon these drugs, which -- spoiler alert -- turned out to be just as addictive as they’ve been since the opium poppy was first cultivated for pain relief and mood alteration thousands of years ago, were being handed out for not just chronic severe pain but other conditions for which less severe medications had always been thought adequate – dental surgery, broken bones, arthritis. Many patients did indeed become addicted, and when they couldn’t get pills anymore, turned to cheap, abundant heroin.

Public health policy has tried to keep up ever since.

In Michigan, along with the MAPS upgrade has come the question of how to get more physicians eligible to use it to register and do so. State laws around prescribing practices and database use vary widely around the country, and Michigan’s monitoring procedures are generally good, said Sherry Green, the incoming president of the National Alliance for Model State Drug Laws, who has made the study of prescription-monitoring programs a focus. But it could be better. LaVoy, the House Democrat from Monroe, sees SB 0769, sponsored by Sen. Tonya Schuitmaker, R-Lawton, as a compromise that was probably necessary, as doctors have resisted mandates in the past, in part because of the MAPS system’s problems.

“MAPS has always been designed to be a clinical tool, used at the discretion of the physician,” said Colin Ford, senior director of state and federal government relations for the Michigan State Medical Society. Responsible doctors already use MAPS, even with its problems, Ford said, and improving it will bring in more, making mandates unnecessary.

“Get a good system on board and see what it does for implementation,” he said. “The crucial step is to get MAPS (working better), then fill in the gaps.”

Concern for chronic-pain sufferers

Ford said health-care professionals are also concerned that after years of warnings about overprescribing by doctors like Linares, policy will swing too far in the opposite direction, making them too cautious in prescribing.

He cited Proposal B of 1999, the Michigan assisted-suicide ballot initiative that failed, which came about over concerns that doctors were unwilling or unable to prescribe adequate pain relief, “even in hospice,” Ford said. Those concerns contributed to the push to offer pain relief far more widely, but as the pendulum swings back toward more caution, “(doctors fear) a chilling effect for those who have a legitimate medical need for an opiate.”

“I speak with a lot of doctors,” Ford said. “The ones I talk to who treat pain with opiates or other therapy are using (MAPS) all the time. Routinely.”

Other states have been more proactive about mandating physician use. Ohio’s monitoring system, known as OARRS, requires all prescribers or distributors of opioids and another oft-abused drug class known as benzodiazepines to use the system. The OARRS system, cited by LaVoy as a model for Michigan, is credited with that state’s decrease in both prescriptions and reports of doctor-shopping (going to multiple doctors to seek drugs) in the past three years.

Use of the Ohio system has grown, as well, from 910,000 queries in 2010 to 15.5 million in 2015, said Cameron McNamee, director of policy and communications for the Ohio State Board of Pharmacy, which administers OARRS. The next upgrade will make it possible to integrate OARRS reports into electronic health records, so that they flow seamlessly into patient charts.

“It’s had a cumulative effect,” McNamee said. “Doctors are finally getting the message that (patients) they thought they could ‘read’ (as drug-seeking abusers) are not the only problem. It’s no longer confined to inner cities, as so many more people have been exposed to these legal forms of heroin.”

Shortage here, abundance there

Another concern, for both doctors and pharmacists, is what happens if an updated, highly used MAPS system is a success, and addicts find it harder to get legal opiates. The heroin epidemic was an outgrowth of pill addiction; when addicts could no longer afford or acquire pills, they turned to the illicit equivalent, which is cheaper and available in both urban and rural Michigan. And Michigan is one state where the increase in fatal opioid overdoses between 2013-14 (13.2 percent) was called statistically significant by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

“Here’s what I’ve been told,” LaVoy said. “Sixty to 70 percent of heroin addicts started on opiate painkillers, many after a surgery or (another legitimate period of use). My fear is, if you stop the flow of pills, people turn to the needle.”

That was the case in Monroe, said April Demers, administrative director of the Monroe County Substance Abuse Coalition, formed to deal with the dragon fed by Linares. Demers said the community (and coalition) was an early advocate for the MAPS upgrade, and did grassroots work to persuade pharmacists and doctors alike to use the system. But she knows what happens when the supply is cut off, but the need remains.

“A community that is addicted (to opiates) with no doctor to prescribe them, that’s when the heroin use spiked,” said Demers. “We’re still reeling.”

And Michigan lacks the treatment capacity for the addicts it already has, said Judge Linda Davis, of Macomb County’s 41-B District Court. She has direct experience, having sent her own daughter, an opioid-turned-heroin addict, out of state for the long-term treatment Davis felt she needed.

Davis served on the Michigan Prescription Drug and Opioid Abuse Task Force, and has asked to serve on the commission of the same name that Gov. Rick Snyder created earlier this summer, to carry out the task force’s recommendations.

“I really think we need to have a more immediate approach to dealing with this,” Davis said. “Kids are dying, elderly are dying, the middle-age death rate is huge. And we’re not as alarmed as we were about ebola.”

We need to recognize, she added, that prescription drug abuse is as dangerous as heroin, and treat it as such, something Linares effectively admitted at his sentencing hearing in June, after pleading guilty to two felonies connected to his abundant prescribing practices.

“I contributed to the prescription drug problem,” Linares told the court as he was sentenced to 57 months in federal prison. “It was simply the lure of easy money. I basically acted like a drug dealer.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Dr. Oscar Linares operated a pill mill in Monroe that prescribed millions of doses opioid painkillers to patients who stood in line for hours to see him.

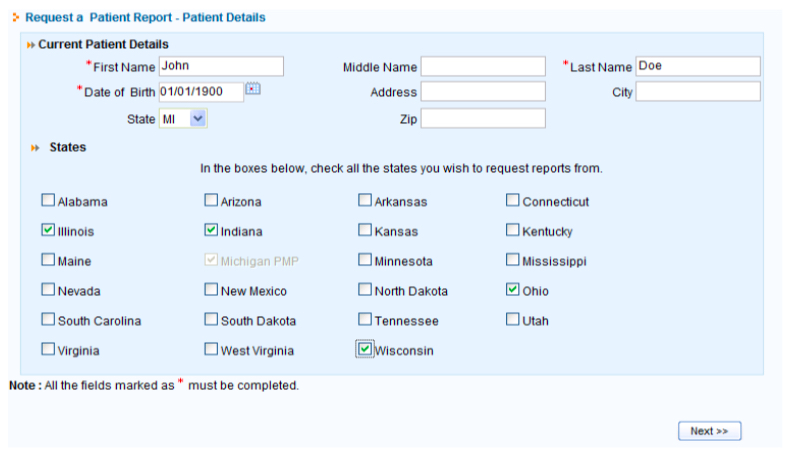

Dr. Oscar Linares operated a pill mill in Monroe that prescribed millions of doses opioid painkillers to patients who stood in line for hours to see him. Users of the Michigan Automated Prescription System can request reports of patients’ prescriptions, a feature meant to identify “doctor-shopping.”

Users of the Michigan Automated Prescription System can request reports of patients’ prescriptions, a feature meant to identify “doctor-shopping.” The Ohio State Medical Association requires doctors and pharmacists to use that state’s drug monitoring system when making prescription decisions.

The Ohio State Medical Association requires doctors and pharmacists to use that state’s drug monitoring system when making prescription decisions.