Deer have Michigan on the run

Michigan’s 2010 firearm deer season was in its first week when a bizarre car-deer accident in suburban Grand Rapids killed a 17-year-old girl.

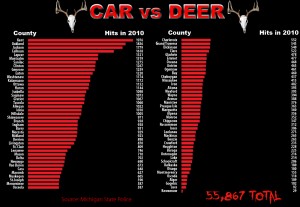

Barbara June Barnick, of Ionia, was driving toward Grand Rapids when an approaching vehicle hit a deer and catapulted the animal into Barnick’s minivan. Stunned by the violent collision, the teen veered off the road and struck a tree, according to police reports. Barnick was one of 11 Michigan motorists killed in the 55,867 car-deer accidents reported in the state last year; another 1,277 people were injured, according to state data.

All were victims of two ominous, divergent trends that endanger motorists and affect many aspects of the state’s environment and economy: Michiganhas too many deer and too few hunters or natural predators to keep the herd in check.

“We’re in a world of hurt,” said Russ Mason, wildlife chief for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources. “We’re losing 2 percent to 3 percent of our hunters every year and we’ve lost 50 percent of our small game hunters over the past 12 years.”

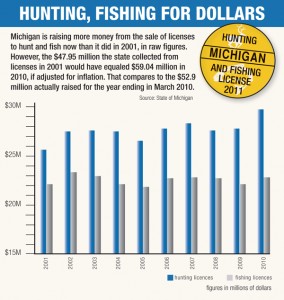

The number of hunters in Michigan has been shrinking since the 1960s, according to state data. Hunting license sales have decreased 15 percent over the past 15 years, from 934,430 in 1995 to 786,880 last year.

The ranks of hunters are shrinking nationwide. But the effects of that trend are especially prevalent in Michigan, where deer dominate vast areas of the landscape, hunters are the primary method for keeping the herd in check and revenue from the sale of hunting licenses funds many of the state’s wildlife management programs.

Fewer hunters mean: Less money for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources to manage wildlife; less money to maintain forests, marshes and other areas where birds and mammals reside; less money for conservation officers who keep poachers in check; and less money for small businesses that count hunters among their best customers.

It also means more deer.

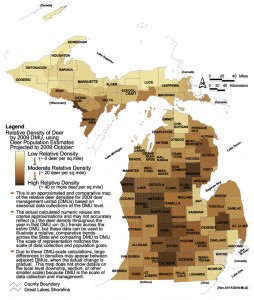

Michigan now has about 1.7 million deer, according to DNR estimates. That’s slightly above the state’s current population goal of 1,567,000 deer; and it’s 51 percent larger than in 1937, when the DNR’s first deer biologist began to talk about the “deer problem,” according to state records.

Dennis Fijalkowski, executive director of the Michigan Wildlife Conservancy, said the massive deer herd has enormous influence over the health of forests and woodlots, which support a vast array of wildlife.

(BRIDGE CHARTS: Michigan's fauna, fish and fowl)

“If you care about birds and like watching birds, what happens with deer affects the birds that you love so much,” Fijalkowski said. “It’s an integrated web of life and it’s out of balance; deer are one of the few species that has the ability to destroy its own environment.”

Hordes of majestic deer are wreaking havoc in numerous areas of Michigan by stripping the undergrowth from forests and eating residential gardens.

Motorists also are in the crosshairs: Deer smashed into Michigan vehicles an average of 153 times each day in 2010. Those accidents caused $130 million in property damage and killed nearly as many people in Michigan as tuberculosis, according to state data.

Wild turkeys also are becoming a nuisance in parts of Southern Michigan. Turkeys were once eliminated from Michigan, but the state has re-established the population over the past three decades.

There are now about 200,000 wild turkeys inMichigan. The birds have become a nuisance in some cities and agricultural areas, prompting the DNR to relocate some of them to the northern parts of the Lower Peninsula.

On the flip side of the issue, business owners who rely on hunting for their livelihood aren’t complaining about the fact of too many deer; they fret about the decreasing number of hunters to go after them.

Ron Lundberg, owner of the Rusty Rail near Escanaba, said business at his tavern has decreased significantly over the past decade.

“When I bought the business in 2000, business was much better; the weekends were always packed,” Lundberg said. “It’s not that we don’t get good crowds now, we just don’t get the crowds we used to get -- and it’s because there aren’t as many hunters as there used to be.”

“When I bought the business in 2000, business was much better; the weekends were always packed,” Lundberg said. “It’s not that we don’t get good crowds now, we just don’t get the crowds we used to get -- and it’s because there aren’t as many hunters as there used to be.”

Lundberg would know: His bar doubles as a state-sanctioned deer check station during the firearm deer season.

The state in recent years has enacted a number of programs to recruit a new generation of hunters and thin the massive deer herd in Southern Michigan. The Legislature in September passed a law that allows children as young as 10 to hunt deer, bear or elk with a firearm, provided an adult supervises them. Next year, the state will eliminate the minimum age requirements for hunting as part of the new Hunter Heritage Act.

The DNR allows hunters to kill more antlerless deer than in the past. And the agency pays farmers in Southern Michigan -- where the deer herd is most concentrated and public land for hunting is most scarce -- to allow hunters to shoot deer on their land.

“One of the major obstacles we face in Southern Michigan is that the vast majority of the land is privately owned,” DNR spokeswoman Mary Dettloff said. “There is a lack of public hunting land, especially in Southeast Michigan.”

The bite at the apple

Many conservationists blame the decline of fishing and hunting on youth sports, particularly soccer, and the soaring popularity of electronic devices -- including personal computers, cell phones, iPods and video games -- that have youngsters spending more time than ever indoors.

“It’s a change in our society,” said Tom Heritier, president of the Saginaw Field and Stream Club.

“I grew up hunting and fishing and being outdoors -- it seemed like the natural thing to do,” Heritier said. “Now you’ve got kids who want to hang out on a computer from the time they get home from school until they go to bed.”

Heritier said the Saginaw Field and Stream Club once attracted 250 children to its annual hunter safety class. “Now we get about 150 kids; that’s happened in just the past 10-15 years,” he said.

At the same time, state funding for the DNR and Department of Environmental Quality has been slashed by nearly 80 percent over the past decade. A recent Michigan State University study found that Michigan ranks 47th nationally in funding for conservation programs.

Mason said there is a simple solution for people concerned about the shrinking ranks of hunters in Michigan and the drop in revenue for conservation programs: Buy a hunting license -- even if you don’t hunt.

“All of those dollars (from license sales) go to the ground, for conservation and wildlife management,” Mason said. “Every dollar of license revenue leverages $3 in support from the federal government. What could be a better deal than that?”

Locals hire professional hunters

Faced with a growing deer herd and little assistance from the state, many Michigan communities and some nature centers are taking up the battle to thin the herd.

Meridian Township, near Lansing, and the Blandford Nature Center in Grand Rapids recently announced plans to shoot deer. The township joined the cities of Marshall, Jackson and Grand Haven and nature centers in Kalamazoo and Midland that now hunt deer to keep the herd in check.

Meridian Township, near Lansing, and the Blandford Nature Center in Grand Rapids recently announced plans to shoot deer. The township joined the cities of Marshall, Jackson and Grand Haven and nature centers in Kalamazoo and Midland that now hunt deer to keep the herd in check.

Efforts to thin urban deer herds have ignited controversy in Grand Haven and Rochester Hills. Critics contend there is no scientific justification for killing urban deer; they also claim there are more humane ways to solve the problem, by sterilizing or relocating nuisance deer.

(Michigan's deer management plan)

Meridian Township Manager Gerald Richards said residents in the community just east of East Lansing and MSU were concerned about car-deer accidents, the potential for deer spreading Lyme disease and the fact that the animals have wiped out countless gardens.

Richards said a former DNR director who lives in Meridian Township estimated there were 2,000 deer in the community, which encompasses 32 square miles.

“He told us we needed to shoot at least a thousand deer,” Richards said. “We’re taking it relatively slow; this year will be a pilot year.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!