How much of Michigan should public own?

On a sunny June day, government officials joined conservation leaders on a Lake Michigan beach to dedicate the newest jewel of the state’s public lands program -- the 173-acre Saugatuck Harbor Natural Area.

On a sunny June day, government officials joined conservation leaders on a Lake Michigan beach to dedicate the newest jewel of the state’s public lands program -- the 173-acre Saugatuck Harbor Natural Area.

The spectacular sand dunes near the mouth of the Kalamazoo River were preserved rather than developed when the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund contributed $10.5 million to a $22 million campaign to acquire the scenic property.

Less than three weeks later, Gov. Rick Snyder signed Michigan’s first law capping the amount of land the state Department of Natural Resources could own.

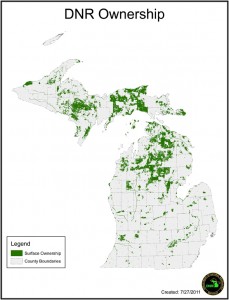

The law capped state land ownership at 4.626 million acres and prevented the DNR from exceeding that cap until the agency develops a land acquisition strategy that the Legislature approves. It also required the DNR to receive legislative approval before buying any more land north of Clare.

The DNR currently owns 4.59 million acres of land and is negotiating purchases on another 18,000 acres. That leaves the agency with an approximately 17,000-acre cushion before hitting the land cap, DNR officials said.

At the heart of the land cap debate was a fundamental, vexing policy question that dates back nearly 75 years: How much public land should Michigan own?

It’s a simple question with no readily apparent answer.

No consensus on ownership figure

"Talking about the number of acres of land the state owns is pointless," said Erin McDonough, executive director of the Michigan United Conservation Clubs. "What we care about is the utility of state land and how we can utilize that land to strengthen the economy."

None of the main players on either side of the land cap debate would provide a figure for how much land the state should own.

DNR critics -- including state Sen. Tom Casperson, an Escanaba Republican who introduced the land cap legislation -- want the agency to own less land. But they wouldn’t say how much less.

Several conservation leaders said the state should own more land, but none would specify how much more.

Steve Sutton, manager of the DNR’s real estate section, said state land acquisitions are driven by a detailed set of criteria, not acreage goals. The new law’s requirement that the DNR develop a land acquisition strategy may help answer the question of how much land Michigan should own, what types of land, and where.

But Casperson said the DNR should forget about acquiring more property in the U.P. or the northern Lower Peninsula.

"The northern part of the state and the U.P. are heavily inundated with government land," he said.

Land cap critics said the law would hamstring Michigan’s burgeoning efforts to use natural resources — clean lakes and rivers, healthy forests and scenic Great Lakes beaches — to bolster tourism and strengthen local and regional economies.

"To say that we’ve got too much public land is very ironic from my perspective, particularly when the state is marketing our recreational assets to the rest of the United States with the Pure Michigan campaign," said Glen Chown, executive director of the Grand Traverse Regional Land Conservancy. "Michigan is known for its recreational assets and we should take advantage of that."

Land numbers haven't changed much

Coming ThursdayPrivate land, public access Fresh off his success in enacting a cap on land purchases by the public Department of Natural Resources, Sen. Tom Casperson is now drafting legislation to make nonprofit, private land conservancies pay property taxes – unless they provide unlimited public access. Conservation groups say Casperson’s idea creates a “no-win” situation. Man with the plan State Sen. Tom Casperson, R-Escanaba, has moved to the forefront of land-use policies in Lansing. So what is his agenda? In a Bridge Q&A, Casperson, who was elected to the Senate in 2010, after previously serving in the Michigan House, discusses his philosophy and his desire to see the state DNR “excel.” |

So how much public land should Michigan own? It’s a question that dates back nearly a century.

The state began acquiring land in 1902, after a 60-year logging frenzy left much of the state a barren wasteland. By 1940, the state had amassed nearly 5 million acres of land — most of which was tax-reverted property in northern Michigan that logging firms abandoned after harvesting the virgin pine forests.

Concerns about excessive state land holdings prompted a 1938 study that included input from nearly 2,000 landowners. They faced one question: How much public land should the state own north of Saginaw?

Their collective answer: About 3.8 million acres, according to a 1945 Michigan State University study called, "The Land Nobody Wanted."

At the time, the predecessor to the Michigan Department of Natural Resources owned 4.6 million acres of land north of Saginaw.

Today, the DNR owns 4.59 million acres of land -- virtually the same amount as in 1940. About 85 percent of DNR land, 3.9 million acres, is located north of Clare, just like in 1940, according to state data.

Nationally, Michigan ranks 7th in state land ownership, according to a 1995 study by the National Wilderness Institute. That study was the most recent assessment of government land ownership in all 50 states.

Michigan’s land portfolio dwarfs those in most Great Lakes states, according to the Wilderness Institute study. In 1995, only New York (with 11 million acres) and Minnesota (with 5.4 million acres) owned more land.

Though the state’s total land holdings have changed little since 1940, festering resentment of the DNR’s land acquisition and land management practices climaxed this year with passage of the land cap law.

Critics fear the law could force the DNR to sell land in the U.P. in order to acquire new parcels in the Lower Peninsula.

Supporters said it would require the DNR to live within its means; the agency lacks the financial resources to properly manage all the land it already owns.

Need for land-use plan is point of agreement

The one part of the law that drew widespread praise was a provision that requires the DNR to develop a comprehensive plan for acquiring and disposing of state land.

"The Legislature has told the DNR to come back to them and do a better job of justifying your land purchases," said Rich Bowman, director of government relations for The Nature Conservancy’s Michigan chapter. "Frankly, I think that’s a good thing."

The DNR’s Sutton said the agency has done a good job of acquiring land, but has failed to convey the program’s economic and environmental value to the public.

"We need to really promote public land ownership and what a huge economic value it is," Sutton said.

Public land is a pillar of Michigan’s $17 billion tourism industry. The forests, beaches and surface waters the state owns or manages provide many of the backdrops for the Pure Michigan advertising campaign.

Conservation leaders said that public lands and natural resources could play a major role in the effort to reinvent Michigan’s economy. A recent MSU study highlighted the economic value of so-called "green assets." It found that the Rifle River Recreation Area in northern Michigan generates $1.8 million of economic activity annually and creates 38 jobs.

Grant resultsA few examples of projects that received grants from the Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund. * $12.5 million toward the purchase of 5.5 miles of Lake Superior shoreline and 6,275 acres of rugged forest on the tip of the Keweenaw Peninsula. |

"Considering the fact that the park is only 4,450 acres in size, the estimated annual economic impacts are quite significant," according to the study.

Trust fund undergirds land buys

The Michigan Natural Resources Trust Fund is the DNR’s primary funding mechanism for land acquisitions. Established in 1976, the fund uses royalties derived from oil and gas wells on state property to buy environmentally sensitive land and develop community facilities that enhance recreational opportunities.

The Trust Fund has provided $1 billion in grants to the DNR and local units of government since 1976, according to state data. The DNR has used Trust Fund grants to acquire 161,000 acres of land since 1976, according to state data.

Although Trust Fund grants have purchased just 3 percent of all state land, many of those acquisitions were significant to the state’s Pure Michigan brand. (info box)

Trust fund grants have: Expanded the Pigeon River Country State Forest and preserved rugged forests in the Keweenaw Peninsula; provided public access to coastal sand dunes, beaches and rivers; and supported upgrades at several marinas and municipal campgrounds. The trust fund also played a crucial role in developing Michigan’s first urban state park: William Milliken State Park in downtown Detroit.

Though widely praised, the Trust Fund was caught in the political crossfire over the land cap. Casperson led a successful effort to remove $4.3 million in Trust Fund grants for DNR land acquisitions in so-called "eco-regions" in the northern Lower Peninsula and the U.P.

The Legislature rejected those grants because the DNR didn’t identify specific parcels the agency hoped to acquire.

Sutton said eco-region grants were always vague, by design. He said the grants allow the DNR to consolidate land holdings in certain areas and act quickly when desirable land becomes available.

The Legislature’s rejection of the eco-region grants marked the first time state lawmakers have overruled the Trust Fund board’s recommendations for specific grants.

But it wasn’t the first time the vaunted Trust Fund has been scrutinized.

A 1988 study by Lansing-based Public Sector Consultants found that most Trust Fund grants went to projects in Northern Michigan, far from the state’s most populous regions. That trend continues to this day, according to state officials.

Sutton said the DNR is making a concerted effort to acquire more public land and provide more recreational opportunities in southern Michigan. The Trust Fund, for instance, poured $34 million into the Detroit Riverwalk project, which included Milliken State Park.

"It’s hard to acquire land in southern Michigan because the prices are higher and there aren’t many parcels of land that meet our criteria," Sutton said.

Ironically, the land cap could make it more difficult for the DNR to buy property where public lands are most scarce and most needed -- in the southern part of Michigan.

Jeff Alexander is owner of J. Alexander Communications LLC and the author of "Pandora's Locks: The Opening of the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Seaway." He’s a former staff writer for the Muskegon Chronicle.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

CLICK TO ENLARGE

CLICK TO ENLARGE