Legislature + lobbyists is a match made with money

Willie Sutton reputedly said he robbed banks because that’s where the money was.

Freshmen lawmakers new to the ways and means of Lansing find the same principle applies when replenishing their campaign accounts mere weeks after taking the oath.

Where the money is for that purpose can be a quick step across the street from the committee rooms where legislation is drafted, or the House and Senate chambers where the bills are voted on. Writing the $150 checks (or more) are the same lobbyists who on those same days testified in those committees or pressed their positions in the Capitol hallways during session.

Six-dozen House freshmen elected on a 2010 wave of voter disgust over the conduct of politics collected more than $500,000 last year in such fashion. On average, Lansing fundraising generated about a third of all the money they received in 2011. For some lawmakers, it was more than 70 percent.

The checks were collected at breakfasts in the Mutual Building next door to the Anderson House Office Building, at lunches at the Beer and Wine Wholesalers Association headquarters, and after-session functions at the lobbying firm Karoub Associates.

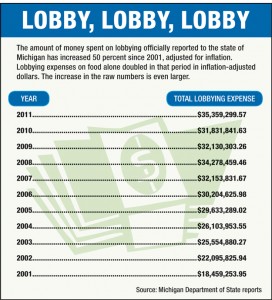

Who pays the price of admission at these Tuesday, Wednesday and Thursday gatherings? Just about any lobbyist or association executive with access to political action committee accounts that assembled $1 million a month in first nine months of 2011.

While the practice of Lansing fundraising is hardly new, its current prevalence suggests that those who ran against the “broken” culture of Lansing don’t yet feel obligated to reform it.

During the term-limits equivalent of the cretaceous period two decades ago, some lawmakers suggested banning the daily juxtaposition of taking money from lobbyists being paid to tilt legislation this way or that. One solution offered: Close the fundraising window for legislators, or at least the acceptance of PAC checks, until after the filing deadline for office closed in the spring. (This year's filing deadline is May 15.)

The idea never went anywhere in Michigan, even though such restrictions on fundraising during legislative session days are in place in 29 states, including some with full-time legislatures like Michigan's.

Such laws don’t preclude a legislator from ever receiving a campaign contribution from a special interest. But they do seek to limit the transactional appearance of lawmaker-lobbyist relationships that have contributed to public cynicism with the process.

Such laws don’t preclude a legislator from ever receiving a campaign contribution from a special interest. But they do seek to limit the transactional appearance of lawmaker-lobbyist relationships that have contributed to public cynicism with the process.

That appearance, of course, leads to the assumption that the PACs and the lobbyists that control them are getting something of value beyond a cup of coffee or a cocktail with a lawmaker.

Not so, says Sterling Corp.’s Steve Linder, a Republican fundraiser.

“The act itself of raising money is not a bad thing,” he said. “The Legislature has great sway over broad swaths of the private and public sectors. (Interest groups) quite frankly have a right to champion those (legislators) who are going to champion their issues.”

“The inference that there’s some direct relationship between money and votes is sheer nonsense,” Linder said.

Rep. George Darany, a Dearborn Democrat, said he was surprised to learn there was no state law barring the distribution of campaign checks in legislative office buildings or other state property. Instead, it’s prohibited by internal House and Senate rules. So he introduced legislation that codifies the ban in statute. He also had a Lansing fundraising event last year.

Darany, in his first term in the House, said the events give newcomers like himself a chance to meet 50 or 60 lobbyists in one location that he’ll be working with over the course of his first term. Such “relationship building” is part of being a legislator.

With dozens of new lawmakers coming in every two years because of term limits, “the fundraiser gives you the chance to match the name with the face,” said one lobbyist. “It’s chit chat, getting your face in front of the legislator every once in a while. Most of the time it’s ‘thanks for coming and eat some food.’ ”

It’s not so much that lawmakers view their access as something to be sold. Or that lobbyists see access as something to be bought. Think of the Lansing fundraising culture as club membership with rewards.

Thanks to term limits (no more than three terms in the House -- six years total -- and two terms in the Senate -- eight years total), there are more new members every two years. And as soon as they get to Lansing, they are deluged with unfamiliar issues and peppered by leadership officials with advice to pay off their old campaign debts and prepare for the campaign ahead, to ensure both a newcomer's re-election and boost their party's prospects for power.

“They come in here and they don’t know anything, so they’re dependent on lobbyists for both the policy perspective and the money,” said Rich Robinson, executive director of the watchdog group Michigan Campaign Finance Network.

What has been a long been lack of concern with appearances -- as evidenced by the appetite for PAC checks when the Legislature's in session and the reticence to require their disclosure on a timely basis -- can lead the Legislature’s reputation into the deeper waters of the perceived quid pro quo.

Two governors, one bridge

When former Gov. Jennifer Granholm was proposing to build a new bridge over the Detroit River, Republicans who had taken tens of thousands in contributions from Manuel "Matty" Moroun and his family, which owns the Detroit International Bridge Co. and the Ambassador Bridge, could base their opposition on distrust of a Democratic administration.

When they presented the fiscal 2013 budget on Feb. 9, Gov. Rick Snyder and Lt. Gov. Brian Calley reiterated their support for what's now known as the New International Trade Crossing, which was shelved last year by their Republican allies who control the House and Senate. The administration's restatement came on the heels of campaign finance reports that the Moroun family had donated about $250,000 to various candidates and political party committees in 2011.

The Legislature’s refusal to advance a project backed by a GOP governor and most of the state’s business community could lead a citizen to the logical conclusion that money, not partisan hostility, was stalling an up-or-down vote on the bridge all along.

Now the easiest way to demonstrate that the Moroun contributions haven’t been an influence would be to schedule floor votes on the bridge concept once and for all. For their part, NITC backers believe bipartisan majorities could be cobbled together.

But here is where the landscape really has changed in Lansing -- changes that mix the existing money culture with a healthy dose of simple fear.

If the Morouns can spend millions on TV ads in legislative districts warning lawmakers not to support a bridge that competes with their own, they can certainly spend $100,000 backing someone in the August primary or the November general to threaten the re-election of incumbents and a Republican majority in the House.

Huge sums of outside, largely undisclosed money could be a deciding financial factor in which House members come back for another two-year term and which party will control the chamber in 2013. And the impact of such "outside" spending is not a hypothetical matter; it's template can be found in the rancorous statewide campaigns for the Michigan Supreme Court, including a 2008 campaign that defeated incumbent Chief Justice Clifford Taylor. The 2010 Supreme Court campaign consumed more than $11 million, a majority of it spent on independent advertising with dollars that didn’t have to be reported thanks to Michigan’s lax disclosure standards. An interest group can run an issue ad thoroughly trashing a candidate, but absent the “express advocacy” of her defeat, the money that paid for the ad can remain secret under Michigan law.

According to campaign finance statements filed by the Jan. 31, 2012, deadline, the average House member had $30,000 cash on hand -- and $20,000 in debt. Take the two main caucus PACs for Democrats and Republicans, double their combined balances of $1 million, and that represents just $160,000 for the dozen or so competitive seats that will determine if the GOP keeps the House or Democrats regain control.

Democratic strategists say gaining the 10 seats required to flip the House could cost as much as $10 million worth of radio, cable, broadcast TV, mail and, yes, robocalls. Republicans and their backers say they’ll be prepared to spend that much to keep it.

“Citizens want transparency, but that’s not what the interest groups want,” Robinson said. “That’s the dilemma. And the interest groups are winning.”

Peter Luke was a Lansing correspondent for Booth Newspapers for nearly 25 years, writing a weekly column for most of that time with a concentration on budget, tax and economic development policy issues. He is a graduate of Central Michigan University.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!