Michigan 'weak' in lobbying oversight

Two relatively narrow economic interests come to Michigan's Legislature seeking movement on issues that have tied the place up in knots for years.

The primary argument of both lobbying efforts to a House and Senate dominated by Republicans is that consumers deserve choice from among the options free and open markets can provide. Other interests with lobbying forces of their own fight back with warnings of economic damage.

The one effort, a big expansion in virtual K-12 learning by private companies, is succeeding, so far. The other, allowing motorists to buy less-than-unlimited medical coverage in their auto policies, is not. But since just about anyone with a stake in the outcome of what goes on in the Capitol has a lobbyist, grabbing wins and taking losses are all part of how the game is played.

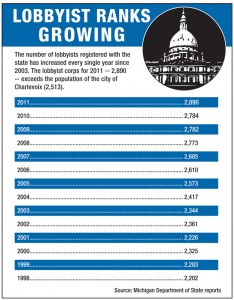

Lobbying has been going on in the Capitol’s hallways forever -- and business is flourishing. Reported lobbying expenditures in 2011 totaled $35.3 million, according to Michigan Secretary of State summations. That's up 86 percent from 2001. The 2,890 business, association, labor and multi-client lobbyists that registered with the state are up 30 percent in number compared to a decade ago.

Beyond those basic details, how much was specifically spent on that lobbying, who was lobbied by whom and for what purpose remains opaque thanks to Michigan's minimal reporting requirements.

If voters had a more accurate idea of just how much effort is put into lobbying, they might have an even dimmer view of their representative government in Lansing. This could be one reason why The Lobby Act of 1978 has undergone so little revision over the years.

Though registered lobbyists are required to report their expenditures, among them individual food and beverage costs that exceed $55 in a given month or $350 in a given year, there is no requirement in the law to specifically report how much they paid either in in-house salaries or multi-client contract fees.

A new survey of state lobbying laws by Washington, D.C.-based Center for Public Integrity labeled Michigan’s reporting requirements to be “weak,” meaning they are “so incomplete or overly general as to render them useless in understanding a lobbyist's expenditures.”

“Strong” reporting, the center said, records which interest groups are lobbying which side of a particular issue, salaries earned the amount of contracts signed. Texas, which requires such detail for example, is considered a "strong" state.

Michigan did high marks from CPI for making the reporting that is required readily available to the public. But it earned poor marks for failing to verify through auditing whether the records filed with the state are even accurate.

Michigan did high marks from CPI for making the reporting that is required readily available to the public. But it earned poor marks for failing to verify through auditing whether the records filed with the state are even accurate.

Process in practice: cyberschools

There are two essential aims to most lobbying. Pass legislation that is in your economic interest. Defeat legislation that isn’t. It helps if the cause being pushed matches the ideology of leader's office.

That’s why after persistent effort and backing from the Snyder administration, for-profit, online education firms are on the brink of a huge victory. Senate Bill 619 lifts existing enrollment caps and expands the number of firm eligible for $7,100 in per-student aid from two to 15. If just 1 percent of the state’s school-age population enrolls -- about 16,000 students -- full-time virtual education will be a $100 million business in Michigan.

Herndon Va.-based K-12 Inc. and Connections Academy out of Baltimore, which, under current law, are limited to a maximum of 1,000 students each, have their own in-house lobbyists and multi-client firms working the bill. If the Senate-passed measure wins House approval, Gov. Rick Snyder will sign it into law.

Also pushing final passage are the half-dozen public universities in the business of authorizing charter schools as well as their umbrella organization, the Michigan Council of Charter School Authorizers.

“Every (Republican lawmaker) is getting hit four or five times with four or five different arguments from four or five multi-clients they have relationships with,” said Robert LeFevre, director of education policy at Macomb Intermediate School District. “That’s not to say we don’t have lobbyists, but we don’t have those kinds of resources."

Charter school advocates scoff at that because public schools employ dozens of lobbyists to advocate on a wide variety of issues such as teacher tenure, employee benefits, retirement costs and funding.

So, on this issue, a lawmaker can vote against the wishes of the Michigan Association of School Boards knowing he'll be voting to support local schools down the road on some other issue involving, say, employee relations or the school foundation allowance. For those groups and individuals pushing choice, among them strong backers of the Republican Party, the cyber bill and companion measure that lifts the cap on brick-and-mortar charter schools represent the No. 1 issue on their education agenda.

The top issue for Michigan hospitals and physicians this year is blocking amendments to a no-fault insurance law that has provided unlimited lifetime medical benefits to accident victims for three decades.

Insurers aren’t waving the white flag just yet, but a proposal that replaces unlimited care with choices of coverage that top out at $5 million has been sitting on the House floor for four months now and has limited prospects in the Senate. Minimum coverage would be capped at $500,000.

House Bill 4936 would also impose a fee schedule on health care providers similar to the one in place for workers injured on the job. Auto insurers complain that surgery charges are three times higher for a shoulder injured in car than on a construction site.

Warnings of billing losses from local doctors and hospitals combined with visits from accident victims in wheel chairs is proving to be potent in ways school opposition to cyber schools is not. Parents aren’t marching on the Capitol to protest a potential $100 million diversion from a $12 billion budget of state aid for K-12.

“We’ve got health care delivery that no other state has and an (unlimited) no-fault mechanism to support it, said Peter Kuhnmuench of the Insurance Institute of Michigan. “I’m taking on folks that have providing these services for 30 years and they don’t like it when I ask them to take on a fee schedule.”

Peter Luke was a Lansing correspondent for Booth Newspapers for nearly 25 years, writing a weekly column for most of that time with a concentration on budget, tax and economic development policy issues. He is a graduate of Central Michigan University.

Editor's note: The Center for Michigan, Bridge Magazine's parent organization, is registered as a lobbyist with the state of Michigan. but does not lobby on individual bills before the Legislature. CFM lobbying expenses reflected in this state report consist of a retainer for a multi-client lobbying firm that helps coordinate educational meetings with lawmakers of both parties on such topics as the Bipartisan Caucus, early childhood funding, corrections spending (via the Corrections Reform Coalition) and the Center's public engagement campaign. The Center has not made contributions to political candidates or parties.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!