Michigan’s Tea Party battles for GOP's soul

It’s the second Saturday of August, as a group of political newcomers gathers in a classroom of a Baptist school near Lansing. They are plotting a political coup. Among their many goals, they want to dump Republican Lt. Gov. Brian Calley and replace him with one of their own. They’d like to repeal or at least weaken Obamacare. They don’t have much political experience. They don’t have much money. They don’t have a formal political machine structure. Yet they’ve quickly gathered stunning momentum in the state capitol. They’ve helped block Gov. Rick Snyder’s proposed gasoline tax hike for roads, stalled funding to implement Common Core education standards, and generally pushed the Republican Party to the right.

It’s the Tea Party Alliance, a little-known and loose confederation of about two dozen Tea Party groups from around the state that gather every month to share ideas, seek common ground and plot strategy.

“A lot of people thought our movement had gone away,” said Bob Murphy, head of the Lapeer County Tea Party Patriots and a member of the alliance. “We’re not standing out on the street with signs anymore. We’ve matured. It’s not all rage and hatred. We want people to listen to us.”

Many Republicans in the state legislature are listening. Some are reluctant not to, fearing they will be blacklisted or face more-conservative candidates in a primary election if they don’t toe the Tea Party’s line.

The power struggle inside Michigan’s capitol has shifted in the past three years. For generations, it was Democrat versus Republican. Now, it’s often Tea Party versus Republican. And the soul of the GOP is at stake in the 2014 statewide elections and beyond.

The leverage of fear

Many in the Tea Party feel they are entitled to be heard. They take credit for the Republican sweep of all statewide offices in 2010, including control of the House and the Senate. With Tea Party support, the legislature and Gov. Rick Snyder made Michigan a right-to-work state.

But that’s not nearly enough to satisfy Tea Party aspirations.

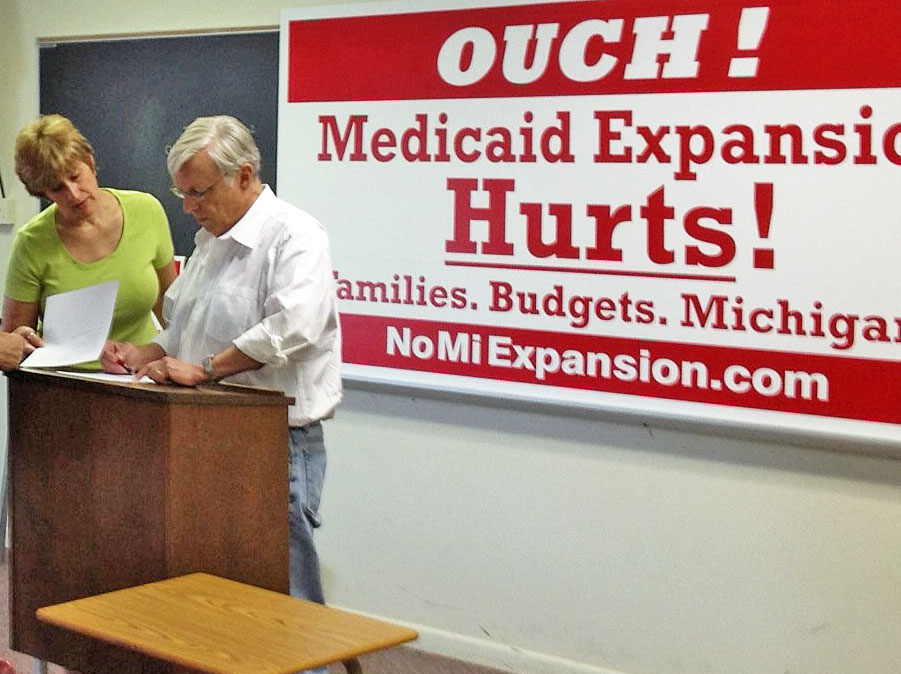

The Tea Party suffered its first major policy loss in late August when the Michigan Senate approved a bill expanding Medicaid under Obamacare. The Tea Party response was bellicose and portends more ideological fights to come.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” one Tea Party blogger responded to the Senate’s Medicaid vote, “it’s time to secure your pitchforks and torches.” Much of their anger is directed at Sen. Tom Casperson, R-Escanaba, who cast the deciding vote. “May you rot in a very hot place, you traitor,” a tea partier posted on Facebook. “…You’re supposed to be one of us.”

A variety of prominent Republicans, including solid conservatives, have faced Tea Party scorn in the past two years on numerous policy issues. Tea Party pressure frustrates key planks of Gov. Snyder’s agenda: The Medicaid expansion took most of this year – and full implementation may take until mid-2014. Road funding remains stalled. A noisy Common Core fight will continue this fall.

Lansing insiders say the Tea Party doesn’t hold legislative majorities, but has gained steam by being loud and threatening.

“There are not a lot of Tea Party true believers in the legislature,” said Ken Sikkema, the former GOP Senate Majority Leader who was term-limited in 2006 after a 20-year legislative career. “But the majority of the Republican caucuses in both the House and the Senate are paralyzed by Tea Party threats of primary challenges next year. These are largely empty threats except in some isolated districts. But having a primary is the worst thing in a legislator’s mind. Having someone challenge you from within your own party is a major sign of weakness – as if you’re not a smart or strong enough politician to avoid a primary.”

Avoiding that kind of worst-case image plays out daily in the capitol. The minute a sitting legislator is clearly vulnerable to a primary, they can begin to lose leverage and bargaining power in the daily negotiations within their committees and caucuses.

“What’s fascinating here is that this is a bluish-purple state, or at least it’s not a blood-red state,” said Charley Ballard, a MSU economist generally seen as left-leaning. “And yet we have a legislature that on many issues is deep red, so red that the business community has only been able to get a modest part of what it wants, despite having a Republican governor and legislature. The business community wants good roads, good schools and Medicaid expansion, and the Tea Party has so far succeeded in preventing these things.”

Once friends, now foes?

Perhaps a testament to the Tea Party’s influence on the GOP is the large number of Republican leaders and their supporters who declined to be interviewed on the record for this story. Snyder’s office did not respond to requests for him or a member of his administration to comment. Numerous Republican lawmakers and business leaders declined to speak on the record.

“You have a politically unruly coalition coming together and having influence,” said Saul Anuzis, a former Republican state party chairman, who was ousted as a GOP national committeeman last year, by a wide margin, by Dave Agema, the Tea Party’s preferred candidate. “They’re active, they’re loud, and they’re involved. The issue is whether it becomes an intolerant and strident organization that’s incapable of working in the system.”

Many in the Tea Party say the system is the problem, and it needs to be reformed, if not replaced.

“When they say, ‘work within the system,’ that means different things to different people,” said Wes Nakagiri, the founder of a Livingston County Tea Party group called RetakeOurGov. “If it means giving up our principles, we wouldn’t fit well into that system.”

In late August, Nakagiri announced he will seek the Republican nomination for lieutenant governor against Calley, a move intended to send a strong message to Michigan’s Republican establishment. If he wins, Nakagiri vowed to vote a conservative, anti-tax line, no matter what his presumed running mate and boss, Snyder, wants.

State Republican Party Chairman Bobby Schostak, who nearly lost his chairmanship earlier this year to a Tea Party-backed candidate, treads lightly when he talks about the Tea Party. “We will do all that we can to protect Brian Calley,” he said, yet he praised Tea Party members for their engagement in the political process, adding that “they’re more than welcome” in the Republican Party.

Replacing Calley “defies logic,” House Speaker Jase Bolger, R-Marshall, said. “The reason I say that is Lt. Gov. Calley is very conservative, and he works closely with the governor. To dump him for someone else is to give up that influence.”

Bolger is not a Tea Party favorite, particularly because he voted to expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act. Voting ‘no’ would have meant turning down the 100 percent federal funding for the expansion the first three years and 90 percent in subsequent years.

“There are some in the Tea Party who believe we should do nothing,” Bolger said. “For me, I had to come to the realization that to do nothing is not an answer. I understand their opposition to Medicaid expansion. I do not support Obamacare, yet, as a legislature, we have to play with the cards we’re dealt.”

Critics accuse Tea Party members of not understanding the difference between politics and governing, and they fault it for using threats and intimidation to get its way.

“They (Tea Party members) don’t know how to play with others and get things done,” complained state Rep. Joe Haveman, R-Holland. “I still believe I’m a conservative, but I try to reach across the aisle and work with the Democrats. Part of the problem with the Tea Party is they’ve never done it. They’re so pure, but there’s a difference between what they want and what they can get.”

Haveman conceded he was reluctant to speak publicly about the Tea Party. He is among dozens of Republican state legislators listed on a “wall of shame” by an Ingham County Tea Party group called Grassroots in Michigan for voting to set up health insurance exchanges or expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act.

Haveman called such tactics “politics at its worst. Do they really believe my door is open to them when they use those kinds of tactics? If they think this is how to work, getting down in the dirt and calling names, then shame on them. I wish the Tea Party would be as nasty and arrogant with the Democrats as they are with the Republicans.”

Looking ahead to 2014

In Michigan, the Tea Party largely ignores the Democrats as beyond hope, directing their pressure, and frequent ire, at Republicans. And Democrats, in the minority in both legislative chambers, have not often moved toward policy compromises that might in some ways marginalize the Tea Party’s far-right influence. Instead, some Democratic leaders seek to leverage Tea Party momentum to paint the larger GOP with an extremist brush in hopes of picking up traction and seats in the 2014 elections.

“I do think the Tea Party has stifled the Republicans, really paralyzed them in some important ways,” said Senate Minority Leader Gretchen Whitmer, D-East Lansing. “When right-to-work was being debated, threats were being made: ‘If you don’t vote for this, we will take you out.’ I know for a fact I have (Republican) colleagues who are scared of being primaried. Unfortunately, there are members who put their own personal interest above getting things done.”

Tea Party leaders concede the threat of a primary election challenge is among their most powerful weapons. Some Republican lawmakers fear a primary opponent more than they do any candidate the Democrats can put up against them in a general election. That’s because legislative redistricting has carved out a range of seats generally deemed safe for Republicans.

“Gerrymandering makes it easier, in my view, for us to run in a primary,” Nakagiri said. “We fight a guerrilla war if you think about it. We don’t have a standing army or the artillery of deep pockets. I would say on the issues that are important to us, we have strong views, and we’re not shy about making our views known. I don’t see that as bullying.”

Sen. Rick Jones, R-Grand Ledge, a self-described Reagan conservative, is among those on the Tea Party’s wall of shame for supporting a statewide health insurance exchange. He’s heard rumors he could face a primary challenger next year.

“When I hear a self-declared Tea Party member say, ‘you better do this or else,’ I say, ‘Bring it on,’” he said. “I guess there may be some members who fear that. I don’t. I don’t know that they have as much influence as the media portrays.”

One reason, he said, is the Tea Party lacks a strong, statewide organization, and is instead fragmented into scores of independent groups scattered throughout the state. Some consist of a few people gathered over coffee. Some are virtual tea parties meeting only through Facebook. Others attract hundreds to their meetings. Most don’t have formal membership rolls, so it’s impossible to say how many Tea Party members are in Michigan. Most have not formally created nonprofit corporations. Many operate without a formal hierarchy of officers.

“The people who generally do this are type A’s,” Bob Murphy, the Lapeer Tea Party head, said, motioning to two dozen men and women gathering for the Tea Party Alliance meeting in August. “They don’t want a lot of organization. It’s like herding cats. I think the alliance thing is the closest we can get.”

Real momentum? Or just noise?

Tea Party critics maintain the noisy tensions between the Tea Party and the GOP are just that – noise. Yes, critics acknowledge, the Tea Party has slowed Gov. Snyder’s business agenda. But, they add, the Tea Party is so self-marginalized at the extreme right of state politics, these idealists have no hope of actually acquiring true legislative majorities or higher offices in statewide elections.

“What has the Tea Party actually won?” asks prominent Lansing public relations executive Roger Martin, whose firm faced down the Tea Party last year on Proposal 5. Martin and company fought back that proposed constitutional amendment that would have required legislative super majorities for any form of state tax increase.

“Proposal 5 was the Tea Party’s big chance and they got completely trounced,” Martin said. “They can’t win at the statewide level because they are out of step with the mainstream.”

Ideological split from within

The Tea Party Alliance exercises no control over its member groups. Each is fiercely independent. That independent streak results in fragmentation even within the Tea Party.

Several of Michigan’s Tea Party groups have not joined the Tea Party Alliance, but align with another loose coalition that is so informal it doesn’t have a name. Representatives of those groups meet three or four times a year and include social as well as fiscal issues on their agendas, said Cindy Gamrat, founder of the Plainwell Patriots.

Last year, some Tea Party Alliance members supported Bobby Schostak for Republican Party chair, while members of the unnamed coalition generally backed challenger Todd Courser, said Gamrat, who was Courser’s vice-chair running mate. They nearly unseated Schostak at the GOP state convention.

“We nearly took over the (Republican) party,” she said, adding that “there’s a general feeling that the Alliance groups tend to be more moderate.”

That is hardly a word most Tea Party Alliance members would use to describe themselves. For their monthly meeting, they came from Ann Arbor, Manistee, Mount Pleasant, Troy, Grand Rapids, Brighton, Ionia, Plymouth, Lansing, Lapeer, Port Huron and Howell and took their seats in the classroom. Most are middle-aged or older.

“I have grandkids, and I want them to know the America I grew up with,” one woman said.

They fear America is sliding toward socialism, and they believe the survival of the nation is at stake. Their distrust of the left and Barack Obama is visceral. They are for strict fiscal discipline, free markets and smaller government, including unyielding opposition to Obamacare and Medicaid expansion.

“It’s a deal breaker,” said Bill Gavette, representing the Lapeer County Tea Party Patriots. “For a lot of us, this could be a deal breaker with the Republican Party.”

That threat could carry significant weight among Republican leaders, including some who once encouraged the rise of the Tea Party and now are wondering whether it is an ally or an enemy.

“It seems to be a contest to see who can move farther to the right,” said longtime political observer Rich Robinson, executive director of the Michigan Campaign Finance Network, a nonpartisan organization that tracks campaign spending. “I think the monster has gotten off the table and is chasing Dr. Frankenstein around the lab.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!