Racial accusations embroil Michigan Medicaid reform debate

Update: Have an opinion on Michigan’s Medicaid work rules? Weigh in quickly.

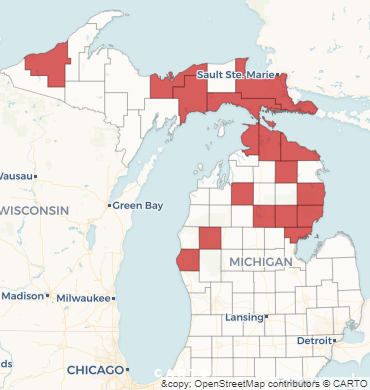

Are Michigan Republicans trying to shield hard-hit residents in GOP-leaning districts from proposed Medicaid work requirements, even as they seek to impose them on poor people living in Detroit and other Democratic-rich cities?

And, more provocatively, does the legislation, if passed, violate federal civil rights laws by disproportionately impacting African-American Medicaid recipients while giving rural, overwhelmingly white regions a pass?

Michigan’s unemployment divide

State legislators may require Medicaid recipients to work at least 29 hours a week, except in counties where unemployment rates exceed 8.5 percent. Six cities and townships, including Detroit, Flint and Saginaw, have similarly high unemployment rates but would not be exempt.

| Would be exempt | Would not be exempt |

|---|---|

|  |

|

|

- *Counties: Mackinac, Cheboygan, Presque Isle, Montmorency, Alger, Roscommon, Schoolcraft, Arenac, Ontonagon, Ogemaw, Chippewa, Emmet, Lake, Alcona, Iosco, Oceana and Kalkaska

- **Municipalities: Detroit, Flint, Saginaw, Muskegon, Highland Park, and Mount Morris Township

Republican backers of the legislation, which would require Medicaid enrollees to provide proof of work to keep their health benefits, find themselves playing defense as the measure moves through the Capitol. Gov. Rick Snyder, a fellow Republican, has already raised doubts about the bill, largely about its requirement that recipients work 29 hours per week.

Related: Four Michigan maps explain debate over Medicaid reform and race

And now arguments are pivoting to what critics contend are the bill’s stark racial and political impacts.

Senate Bill 897 would allow Medicaid recipients who live in counties with high unemployment — at least 8.5 percent — to count an active job search toward their work requirement. As the bill is written, that exemption wouldn’t apply to recipients who live in cities with high jobless rates, like Detroit and Flint, because their surrounding counties fall below the 8.5 percent threshold.

The result: Counties that would be exempt from work requirements — 17 in all, using the most recent March state data — are concentrated in northern Michigan. Their residents are predominantly white, rural and represented by Republicans in the state Senate. Conversely, most of the cities with high unemployment tend to be black and Democratic-leaning.

“There’s no question (in) my mind that the bill has a disproportionate racial impact,” said Nicholas Bagley, a law professor at the University of Michigan who specializes in health and administrative law. “The question that should worry Michigan’s legislators is whether that means the work requirements plan is legally infirm. And I think it is.”

Most Medicaid recipients subject to the rules typically would need to work, or receive education or training toward employment, to keep benefits.

Related stories on Michigan's controverisial Medicaid work requirement bills

Supporters say the idea recognizes that Michigan has different regions with different economic conditions, and prevents Lansing from imposing a one-size-fits-all solution.

The provision has attracted state and national attention, with much of the focus on the apparent racial and socioeconomic disparities between who would and would not qualify. And it could get even more attention, if some legal scholars turn out to be right and it runs afoul of federal civil rights laws.

What supporters say

Sen. Mike Shirkey, R-Clarklake, is sponsoring the bill — his district, which covers Jackson, Hillsdale and Branch counties in southern Michigan, is not exempt from the work rules.

Shirkey said he enlisted suggestions for exemptions to account for differing economic conditions across Michigan.

The Michigan Chamber of Commerce, in response to Shirkey’s request, suggested 8.5 percent as used in a 2014 state minimum wage law, said Wendy Block, senior director of health policy, human resources and business advocacy for the chamber.

Block said the chamber also reviewed U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics data that showed multiple Michigan counties are at or above that rate.

“It’s really not meant to reflect anything but a sign of weakening in the economy,” she said. “Consensus is it’s around that mark where jobs are harder to come by and it would be harder for people to comply with this provision, even able-bodied adults.”

So why not count big cities such as Detroit, whose unemployment rate is 9.5 percent?

Block said it’s easier to track 83 counties than roughly 1,500 municipalities — including cities, villages and townships — in part because the federal government doesn’t break out data for smaller locations.

In an economic downturn, densely populated urban counties could have jobless rates high enough to qualify, said Rich Studley, the president’s chamber and CEO.

“Race was simply not a factor,” he said.

Shirkey went further, telling Bridge that rural residents in northern Michigan deserve more leeway in finding a job than people in places like Detroit or Flint. People in rural counties, he argued, lack public transportation and have to travel farther for work.

“The lower the population, the fewer the jobs. And the lower the population, the greater the distances to the jobs,” he said. “I’ll say that the public transportation system in Southeast Michigan is not as good as it should be, but it’s basically nonexistent in the rest of the state.”

What opponents say

Shirkey’s reasoning fails to understand the transportation challenges facing poor, urban residents, said Bagley, the University of Michigan law professor.

Urban dwellers are less likely to own a car than people in rural areas, Bagley said. And city residents, particularly in Detroit, face steep auto insurance rates that deters car ownership, and a transit system that puts jobs in far-flung suburbs that often aren’t served by buses.

The 17 northern Michigan counties that would be exempt have about 303,000 people combined. That’s less than half the population of Detroit alone, using 2016 estimates.

Bagley said the unemployment exemption could violate a section of the 1964 federal Civil Rights Act, which stipulates that recipients of federal funds — like Medicaid — can’t be discriminated against based on race, color or national origin.

Under the law, it doesn’t matter if the bill was intended to treat minorities differently if the impact of the law does just that, he said.

Emily Schwarzkopf, a policy analyst for the Michigan League for Public Policy, which advocates on behalf of vulnerable Michigan residents, said the only way to improve the bill would be to kill it.

“It seems less about protecting people in struggling areas and more about protecting Republican legislative districts,” Schwarzkopf said. “The barriers to work are no different to someone in Flint, where unemployment is over 10 (percent), than they are to someone in Emmet County. They’re moving a bad bill, and trying to grease it by exempting their constituents. You can't exempt your way to a good policy.”

What’s the status of the bill?

After clearing the Senate last month, the House appropriations committee heard testimony on Shirkey’s bill last week. Gideon D’Assandro, a spokesman for House Speaker Tom Leonard, has said the committee could hear testimony again next week.

But until Republicans can get the governor on board, the House is not in a hurry to send legislation to his desk for his veto.

Shirkey said he continues to negotiate a compromise with Snyder and his staff.

Snyder spokesman Ari Adler told Bridge this week: “The county unemployment rate exemption is just one of a host of issues the governor will continue to work on with Sen. Shirkey as we continue our dialogue on the bill.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!