Tom Hayden, reflections on an old friend

My old friend, Tom Hayden, died last week.

You may never have heard of him until the protest era of the 1960s, when he became nationally famous as one of the Chicago Seven, and later as the husband, for a while, of Jane Fonda.

But Tom and I go back to the late 1950’s, when we were both staffers on the Michigan Daily, the student newspaper at the University of Michigan. Although he was a year younger and a year behind me, we worked closely together agitating to get rid of the Dean of Women Deborah Bacon, organize a student-led Conference on the University and start Students for a Democratic Society (SDS).

In fact, while I was sports editor of a newspaper in Fairbanks, Alaska and Tom was marching in civil rights demonstrations in the South, I drafted part of the preamble of the SDS founding document.

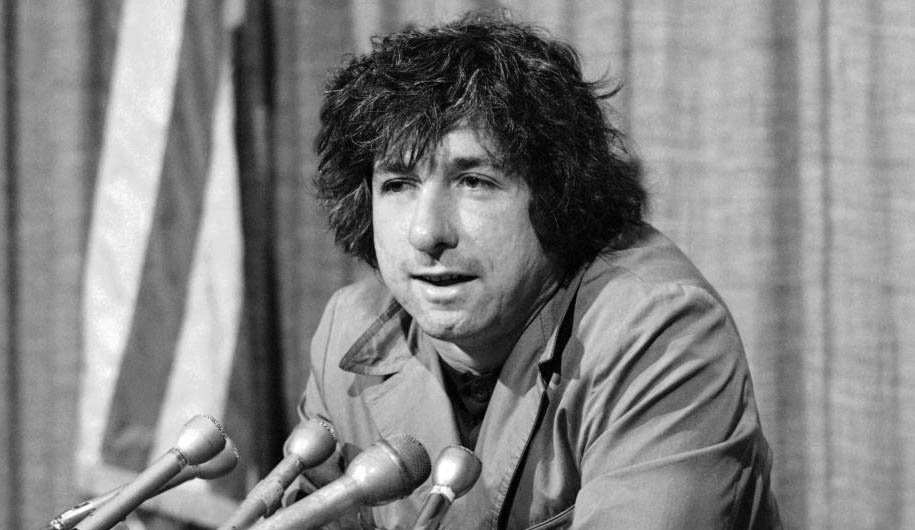

For somebody who became among the most famous of our generation, Tom was not physically prepossessing. Slim, with a nose slightly too large for his pockmarked face and a scramble of wiry hair that turned an early gray, he was hardly likely to be listed in his high school yearbook as most likely to succeed.

But he was very smart, compellingly articulate, and extraordinarily charismatic. Some of our colleagues resented his remarkable ability to bring people into the penumbra of his leadership influence. But to an extraordinary degree, he tapped into our generation’s unease at where the establishment was taking us.

Born in 1939, he grew up in the solidly middle-class town of Royal Oak, where his family was a member of Father Charles Coughlin’s Shrine of the Little Flower parish. Coughlin had been a nationally famous right-wing radio demagogue until silenced by the Vatican during World War II – and I always suspected Tom grew his early rebellious instincts from what he heard from the pulpit.

By the time he got to Ann Arbor, he was entirely ready to join in the The Daily’s distinctive mixture of slightly cynical yet naively hopeful brand of youthful progressive politics. He supported then-U-M President Robben Fleming’s decision to make bail for students who had been arrested demonstrating against the war in Vietnam.

Along with several faculty members, Tom had dreamed up the idea of holding anti-war teach-ins all across campus. He and I drove across the country together the summer of 1960, me to take a job harvesting wheat with migrants in Kansas and he the much more glamorous task of covering the Democratic National Convention in California, the one that nominated JFK, for The Daily.

By the time we got back to Ann Arbor, Tom had married Casey Cason, a beautiful young woman, making all of us slightly jealous. He threw himself into demonstrating against segregation in the South (where he was beaten and hospitalized) and pulling the sprawling student movement into the progressive (radical) SDS.

He went on to national fame as a leader of the Chicago Seven, arrested for fomenting the demonstrations at the Democratic National Convention in 1968 and, after his marriage to Jane Fonda, possibly the leading student activist against the war in Vietnam.

After that, I only saw him on his occasional visits to Ann Arbor, where – not surprisingly – he seemed preoccupied with more important things than his old friends.

But his death leads me to reflect on leadership and how it is expressed in and by various people. In Tom’s case, leadership at an early age was an essential component of his charismatic personality, as easy and as powerful as the rising sun. He didn’t dominate a room when he came in; he was too slight a physical presence for that.

But once he started talking, passionately and earnestly opening his heart and mind, he was a tremendous force.

Such people who come to leadership and fame so young and so easily often find it hard to recognize that times inevitably change and that the instincts that served one so well on the way up become slightly wrinkled and worn as one ages. To be sure, Tom had serious political ambitions once he moved to California: he ran for governor, senator and the mayor of Los Angeles, and was elected to the state legislature, both House and Senate.

But his career as an elected politician – which required him to work with others of differing persuasions but occupying the same positions of power – butted against his instinct to lead his crowd.

Others find longer, more aggregative or consensus-building routes to leadership. Michigan’s former governor, Bill Milliken, and his contemporary, Sen. Phil Hart, over the years grew as leaders through the thoughtful, gradual accumulation of experience, hard-earned judgment, and wise observation of their fellow men and women. They were never skyrockets, but they made a difference in other ways … mostly by just showing up, day after day, keeping at it.

Tom was a flaming Roman candle. He left earth early and suddenly on a spectacular flight that changed a nation’s political climate. He returned from the 60’s to find a slightly different world, one slightly less willing to follow his charisma but still filled with many who admired the once-young man from Royal Oak who could move hearts and minds as easily as the moon moves the tides.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Tom Hayden was an editor at The Michigan Daily and soon expanded his activism into a national campus anti-war and civil rights movement in the 1960s.

Tom Hayden was an editor at The Michigan Daily and soon expanded his activism into a national campus anti-war and civil rights movement in the 1960s.