Let the river run: Dam removal accelerates in Michigan

Michigan may be the Great Lakes State, but its 36,000 miles of rivers are becoming popular commodities for cities looking to revitalize downtowns, attract visitors and lure new businesses.

A growing number of communities across the state — large and small, urban and rural — are removing obsolete dams, restoring fisheries and developing riverside parks and trails.

“The Riverwalk is one of the main attraction tools we use in recruiting new visitors, businesses, and families to Big Rapids,” said Darcy Salinas, executive director of the Big Rapids Downtown Business Association. “Overall, the Riverwalk is one of Big Rapids' major points of pride.”

The city of Big Rapids built its 2.6-mile-long Riverwalk trail along the Muskegon River after remnants of the Big Rapids Dam were removed in 2001. The dam disrupted the river and was a safety hazard: Several people drowned while trying to canoe through unnatural rapids the dam created.

Other cities, such as Detroit and Lansing, have capitalized on water quality improvements in long-abused rivers by developing riverfront parks and trails.

But in a growing number of communities — including Mt. Pleasant, Watervliet, Nashville and Dimondale — the removal of obsolete dams spurred projects that restored fisheries, increased public access to waterways and created new recreational opportunities in and along rivers, such as kayaking and biking.

Experts say Michigan could be on the cusp of an unprecedented era of dam removals and river restoration projects.

“There has been more interest in river restoration and dam removals in the past five years than there was in the previous 10 to 15 years,” said Jim Hegarty, a civil engineer and dam removal expert for the Grand Rapids-based engineering firm Prein & Newhof.

Gov. Rick Snyder’s 2013 budget included $2.5 million for dam removals or repairs. The state Department of Natural Resources recently announced $2.35 million in grants to support dam removals or major repairs in six communities. Four of the grants will help fund dam removals in: Traverse City (Boardman River); Lyons (Grand River); Shiawassee (Shiawassee River); and Vassar (Cass River). (See detailed project descriptions here.)

Federal agencies and private foundations also have provided more money for dam removals in recent years. Michigan’s Great Lakes Fishery Trust and the federal Great Lakes Restoration Initiative funded several dam removal projects in recent years.

But there isn’t anywhere near enough public or private money to address what one study called Michigan’s looming dam crisis.

Michigan’s a dam state, too

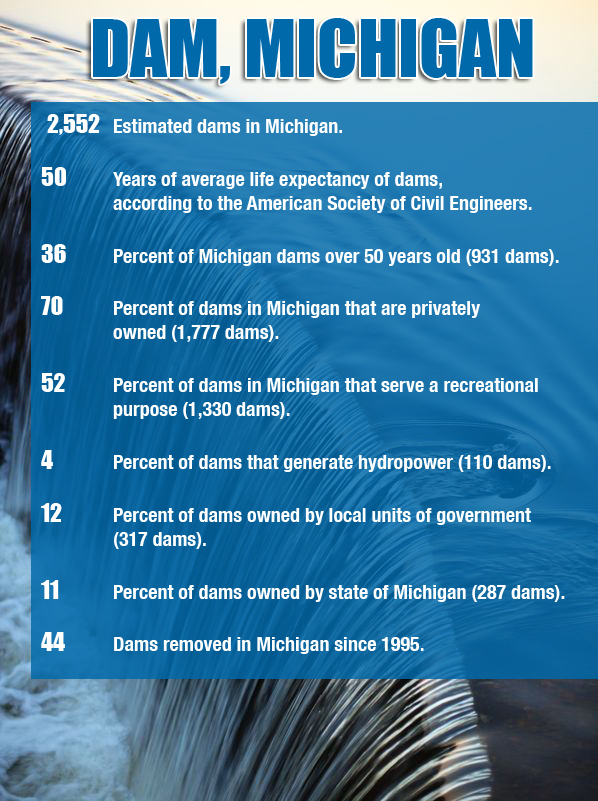

Michigan has 2,552 dams and many will need to be removed or undergo major repairs in the near future, according to a 2007 study by Prein & Newhof and Public Sector Consultants in Lansing. The average lifespan of a dam is 50 years, and 36 percent of Michigan’s dams are at least 50 years old, according to the study.

Most dams in the state are small structures that were built to power sawmills and grain mills, and to elevate water levels in lakes and waterfowl hunting areas; just 4 percent generate electricity, according to state data.

In most cases, removing an obsolete dam costs far less than repairing it, according to the Prein & Newhof study. It concluded that the number of Michigan dams that should be removed would increase steadily and dramatically over the next two decades.

Grand ambition on the Grand River

One of Michigan’s most ambitious and closely watched river restoration projects is unfolding in Grand Rapids. A proposal to remove all or part of the Sixth Street Dam in downtown Grand Rapids and restore naturally occurring rapids has morphed into a $27.5 million whitewater and river restoration project.

Supporters say the project, which won’t use city funds, would attract more visitors to Grand Rapids and pump more revenue into the city’s resurgent downtown.

“A natural asset like our river can be an economic tool for the recreation economy as well as for its shoreline development potential,” Grand Rapids Mayor George Heartwell said.

Heartwell added that the project would be an investment in the community’s future and an important link to the city’s past. “Generations of Grand Rapidians will thank us,” he said.

Critics, however, have argued that creating a whitewater kayak course by removing all or part of the Sixth Street Dam could ruin the popular salmon and steelhead fishery in downtown Grand Rapids.

Nevertheless, several Grand Rapids business leaders and influential philanthropists support the project. So does Snyder.

“Great cities have great waterfronts — that is true everywhere in the country,” DNR Keith Creagh said. He said the state is helping communities revitalize waterfronts.

“The Detroit Riverfront, where the state has made a significant investment, is a great example of those efforts. So is the Grand Rapids river restoration project,” Creagh said.

$100 million spent in Detroit

The Detroit Riverfront Conservancy has spent more than $100 million to develop the Detroit Riverwalk. The paved trail along the Detroit River hosts several festivals, attracts more than 1 million visitors annually and is home to Michigan’s first urban state park: William Milliken State Park.

Hegarty said the scope and location of the Grand Rapids river restoration project, in the heart of Michigan’s second-largest city, make it enormously significant.

“The Grand Rapids project is huge in capital letters,” Hegarty said. “The sheer cost and magnitude of the project are unprecedented in Michigan, but the most significant part of the project is that it has the potential to elevate Grand Rapids’ status as a tourist attraction.”

Dam controversies are common

The largest dam removal project in Michigan’s history is currently under way on the Boardman River in Traverse City. That $10 million project will remove three dams and restore natural conditions and improve the fishery in a large stretch of the popular river that flows through downtown Traverse City before entering Grand Traverse Bay.

The Boardman River project recently sparked public outrage when a dewatering structure at the Brown Bridge Dam failed, sending a torrent of water downstream that flooded several homes.

Dam removal projects in Michigan are often controversial because most dams targeted for removal are community fixtures. Residents often struggle to imagine how removing an historic dam would improve a river, said Chris Freiburger, supervisor of fisheries habitat management for the Michigan Department of Natural Resources.

“In almost every case, the community wants to keep its dam,” Freiburger said. “But wherever a dam has been removed, communities became very excited about the project a year or two after it was completed and vegetation had been restored along the river.”

Jeff Alexander is owner of J. Alexander Communications LLC and the author of "Pandora's Locks: The Opening of the Great Lakes - St. Lawrence Seaway." A former staff writer for the Muskegon Chronicle, Alexander writes a blog on the Great Lakes.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

THE GOAL: An artist’s rendering shows a section of the Grand River in downtown Grand Rapids after a nearly $28 million river improvement project is finished. (courtesy image)

THE GOAL: An artist’s rendering shows a section of the Grand River in downtown Grand Rapids after a nearly $28 million river improvement project is finished. (courtesy image) Demolition work on the Brown Bridge dam on the Boardman River is shown in this 2012 photo. Flooding earlier this year has prompted criticism of the Boardman dam removal efforts. (Bridge photo/John Russell)

Demolition work on the Brown Bridge dam on the Boardman River is shown in this 2012 photo. Flooding earlier this year has prompted criticism of the Boardman dam removal efforts. (Bridge photo/John Russell) Sources: Public Sector Consultants, Prein & Newhof, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality

Sources: Public Sector Consultants, Prein & Newhof, Michigan Department of Environmental Quality