Michigan rivers polluted by human, animal waste more than double previous estimates

Pathogen pollution in Michigan’s lakes and rivers – caused by human and animal waste draining into surface waters – is far more widespread than previously documented, according to new state data.

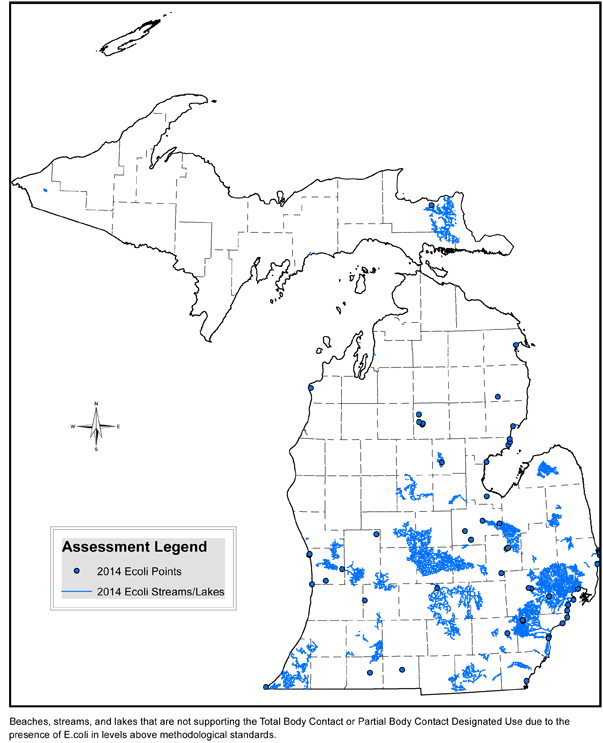

The identification of rivers impaired by potentially harmful pathogens has more than doubled in recent years – from 3,359 miles in 2008 to 7,232 miles in 2012, according to a draft of the Michigan Department of Environmental Quality’s 2014 impaired waters report obtained by Bridge.

Kevin Goodwin, a DEQ senior aquatic biologist, attributed the increase in pathogen pollution to local and state agencies testing more rivers for fecal matter.

“The changes we are seeing reflect better monitoring by the department, not a big change in water quality,” Goodwin said. “The more you look, the more you find.”

Pathogens in surface water can cause a variety of health problems in people who come in contact with contaminated water: stomach ailments, rashes and, in extreme cases, organ failure or death.

Most of the rivers impaired by pathogen pollution are in southern lower Michigan, where there is a greater concentration of people, sewers, leaky septic tanks and farms, according to the report and DEQ officials.

The DEQ report is a biennial inventory of lakes and rivers that have been degraded by chemical or biological pollutants, excessive sedimentation or man-made alterations.

Overall, the report concluded, water quality is good to excellent in most of Michigan’s 872,109 acres of inland lakes, 76,425 miles of rivers and the 41,267 square miles of Great Lakes waters within the state’s borders.

But pathogen pollution has become more widespread. And a lingering problem – airborne mercury and PCBs from sources around the world raining down on surface waters and contaminating some species of fish – continues to haunt most of the state’s lakes and rivers, the report said. A statewide advisory urging people to limit consumption of certain fish, due to widespread mercury contamination, has been in place for years.

“When you look at the whole state, (water quality) looks pretty bleak, but things look better when you remove the mercury and PCB listings,” said Goodwin, who managed the state’s impaired waters report.

Man-made causes

State officials said many sources contribute to pathogens in surface waters: Municipal sewer overflows, polluted stormwater runoff, leaky septic tanks and manure draining off farm fields.

James Clift, policy director for the Michigan Environmental Council, said the Legislature should use some of the current budget surplus to better protect lakes and rivers that are pillars of the state’s $17-billion tourism industry.

“We should invest some of this money into protecting Pure Michigan and maintaining our edge in the tourism industry – and that requires keeping our lakes and rivers clean,” Clift said. “If the product we are selling is Pure Michigan, what are we doing to protect the product?”

Reducing pathogen pollution in surface waters will require reductions in municipal sewer overflow, cracking down on leaky septic tanks across the state and reducing manure runoff from farm fields, according to state officials and environmental groups.

Once the state report is finalized, it will guide state efforts to clean up and restore damaged rivers and lakes, said Shannon Briggs, a DEQ toxicologist. There is much work ahead.

According to the report:

Of the 7,733 river miles assessed for pathogen pollution, 98.4 percent were deemed periodically unfit for swimming. Local health departments are responsible for posting advisories at polluted lakes and rivers, but most agencies only have funds to routinely monitor water quality at the most popular beaches.

The DEQ added 11 Great Lakes beaches to the list of impaired waters. Each of those beaches – scattered across lakes Michigan, Huron and Superior – had potentially unsafe levels of pathogens in the water on multiple occasions in 2011-2012. In each case, health officials posted multiple advisories urging swimmers to stay out of the water when bacteria levels spiked. Because it takes roughly 24 hours to analyze water samples, health officials have said that some people end up swimming in polluted waters before the tests results come back and health advisories are posted.

95 percent of rivers assessed also failed to meet water-quality standards for PCBs or mercury in fish.

84 percent of inland lakes and reservoirs that were assessed failed to meet water quality standards for PCBS or mercury in fish.

None of the 42,167 square miles of Great Lakes waters within Michigan’s boundaries met water quality standards for persistent toxic chemicals in fish.

There were, however, some bright spots in the 2014 report:

More than 85 percent of all beaches on inland lakes and reservoirs that were assessed were safe for swimming.

The vast majority of rivers had healthy populations of macroinvertebrates, an indicator of biological health.

PCB concentrations in fish have decreased in some rivers.

Farms, septic tanks under the spotlight

Previous studies showed leaky septic tanks are polluting Michigan rivers and that farm runoff contributes to a resurgence of algae blooms in western Lake Erie. The algae blooms, which are large enough to be photographed from space, have prompted calls for tighter regulations on farms.

The International Joint Commission, a U.S.-Canada panel that monitors Great Lakes issues, recently urged all Great Lakes states to ban winter application of manure and municipal sewer sludge on frozen fields.

Farmers who spread manure on frozen and snow-covered fields say the practice fertilizes the soil. But manure spread on frozen fields can drain into nearby waterways during rain showers and when soils thaw.

New York already bans manure application on frozen ground and Indiana only allows it in emergencies. Michigan, Ohio and Pennsylvania allow winter manure applications under certain conditions, the IJC noted.

Jamie Clover Adams, director of the Michigan Department of Agriculture, said Michigan opposes a ban on winter manure application because the practice is tightly regulated in the state.

She said the largest livestock farms – so-called CAFOs (Concentrated Animal Feeding Operations, which house thousands of animals) – rarely spread manure in the winter because their operating permits require six months capacity in manure storage lagoons. “CAFOs aren’t spreading manure in the winter because they’ve got enough storage to hold it until the spring comes,” Clover Adams said.

But Lynn Henning, a Lenawee County farmer and anti-CAFO activist who has documented what she portrays as numerous environmental violations by the massive livestock operations, said CAFOs routinely spread liquid manure on frozen and snow-covered fields.

“I had people calling me (in early January) saying that CAFO operators in Clinton County were spreading manure on snow covered fields, at night,” Henning said. “It’s widespread in Michigan and all across the country.”

Clover Adams said it’s unfair to single out agriculture as a major source of water pollution in Michigan.

“We’re not perfect and I would never say we’re not part of the problem,” she said of farmers. “But everyone is contributing – septic systems, municipal sewer overflows and things like that.”

Septic tanks failing, polluting

Michigan has about 1.3 million septic tanks that serve nearly one-third of all homes. On an average day, state residents and businesses flush 264 million gallons of wastewater into septic tanks, according to government data.

At any given time, about 10 percent of septic tanks in Michigan – 130,000 in all – fail and cause pollution, according to state estimates. An unknown quantity of raw sewage from those failed septic systems ends up in lakes, streams and underground aquifers that supply drinking water wells.

Studies show leaky septic tanks are polluting rivers, but little has been done to address the problem because Michigan’s septic tank regulations have gaping holes, according to industry and government officials.

Michigan is the only state without a uniform septic code governing the design, installation and maintenance of the devices. Unlike many states, Michigan doesn’t require septic tank inspections after they are installed.

Eleven Michigan counties have taken the initiative to require septic tank inspections when properties change hands. County officials said the programs have identified thousands of failed septic tanks and kept more than 100 million gallons of raw sewage from seeping into surface waters.

Legislative efforts to strengthen Michigan’s septic tank regulations have repeatedly failed. The Legislature has considered six proposals since 2004 to enact a statewide septic system code, but all died in committee.

Groups representing local units of government, real estate agents and the septic tank industry have all expressed support for a statewide septic code. But concerns about turning real estate agents into septic tank police, or interfering with the authority of local governments to control land use has derailed legislative attempts to address the issue statewide.

“We’ve known about this issue of failing septic tanks for a decade,” said Clift, of the Michigan Environmental Council, “but the Legislature refuses to do anything about it.”

While Michigan lacks a statewide code, local governments cannot ignore leaky septic tanks threatening water quality. In a 2012 case that pitted the DEQ against Worth Township in Sanilac County, the Michigan Supreme Court ruled that municipalities are obliged to address sewage spills that cause water pollution.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Sign warns swimmers of pathogen pollution at a northern Michigan beach.

Sign warns swimmers of pathogen pollution at a northern Michigan beach. Aerial photo shows winter application of livestock manure on a snow-covered farm field in Lenawee County. Farmers spread manure on frozen and snow-covered fields to fertilize soil. Critics say the practice threatens nearby surface waters. State officials say it’s safe when done properly. (Photo courtesy of Lighthawk)

Aerial photo shows winter application of livestock manure on a snow-covered farm field in Lenawee County. Farmers spread manure on frozen and snow-covered fields to fertilize soil. Critics say the practice threatens nearby surface waters. State officials say it’s safe when done properly. (Photo courtesy of Lighthawk) Map of Michigan rivers with high levels of pathogen pollution in 2012, the most recent data available. Farm manure, sewer overflow and leaking septic tanks are blamed for fecal waste in state waters. Most water tested for high waste levels is in southern lower Michigan.

Map of Michigan rivers with high levels of pathogen pollution in 2012, the most recent data available. Farm manure, sewer overflow and leaking septic tanks are blamed for fecal waste in state waters. Most water tested for high waste levels is in southern lower Michigan.