Colleges' ROI more complicated than simple math

Philip Swanson, fresh from earning his degree in civil engineering from Wayne State University, already is among a fortunate minority. While more than 50 percent of college grads under age 25 are either jobless or under-employed, Swanson has secured a full-time job in his field of study.

And, because he earned a baseball scholarship and worked summers, he has no student debt at a time when 60 percent of college grads in Michigan have student loans, and when the average student loan debt in 2010 was $25,675.

That combination means, for the 23–year-old Detroit resident, college was quite a good return on investment.

The same is not true for some students on Michigan's college campuses, according to a controversial study by PayScale.com, a consulting firm specializing in nationwide employee compensation issues.

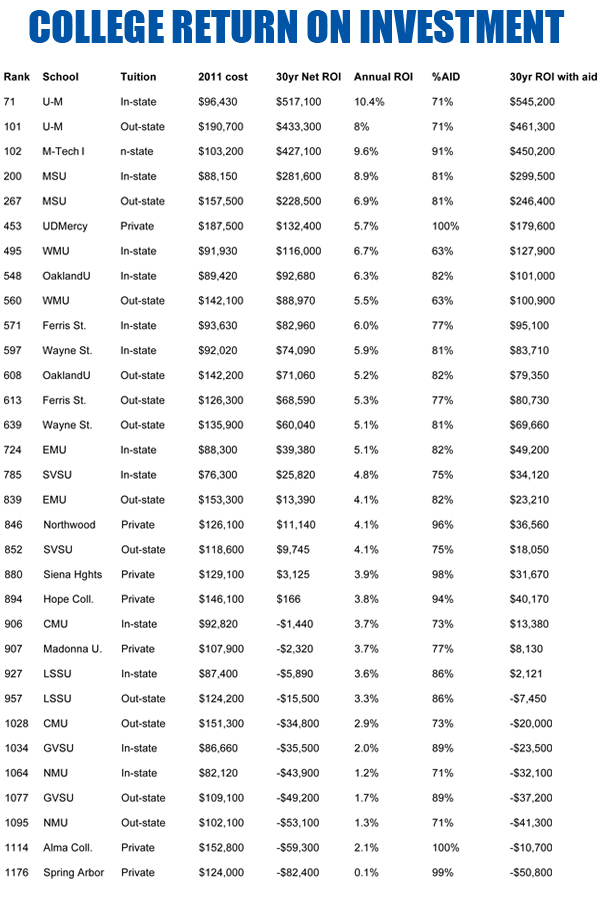

The survey ranked the return on investment over a 30-year period of 853 universities with at least 1,000 undergraduates and found that college may -- or may not -- be a good use of money.

Of the 13 Michigan public universities reviewed by PayScale, four -- Central Michigan University, Grand Valley State University, Lake Superior State University and Northern Michigan University -- were deemed to have a negative "return on investment" in comparing the costs of obtaining a degree vs. the future earnings, based on in-state tuition, and without accounting for financial aid programs. Two private Michigan schools -- Alma College and Spring Arbor University -- had the worst ROI among all Michigan schools reviewed.

“College is not the investment it’s cracked up to be,” said PayScale’s head economist, Katie Bardaro. “There’s been a lot of research done that claims college is a $1 million return. The problem is the way this research has been done in the past is looking at aggregated data and not taking into account different cost structures, or different lengths of time to graduate, or the cost you lose out in wages by going to school rather than working.”

When those variables were considered, PayScale found that only nine schools on the entire list offer $1 million or more return on investment, and the return on investment falls off quickly after that.

“And in a lot of cases, it goes negative,” said Bardaro.

Michigan schools in PayScale.com survey

At Grand Valley, one of the "negative" cases for PayScale, the website's methods came under a negative review of their own.

"We do not believe that Payscale.com's methodology produces an accurate analysis of ROI at Grand Valley State University," said spokesman Matt McLogan.* "Payscale's own fine print makes clear why this is so:

"'We are effectively assuming the (wage inflation adjusted) earnings 30 years from now for a 2011 graduate are the same as the current earnings of a 1982 graduate. If the character of a school's graduates has changed substantially in the last 30 years, this measure may be inaccurate.' Payscale's last sentence describes Grand Valleyto a T. Grand Valley today differs greatly from the Grand Valley of 1982. The high-paying professions being pursued by many of today's Grand Valley graduates weren't offered at Grand Valley 30 years ago."

Central Michigan University spokeswoman Sherry Knight says the Payscale study isn't reliable because it uses data submitted by individuals requesting insight into how their salaries compare to others' salaries, and therefore does not reflect a complete or random sample.

She said the fact that Payscale finds that some students actually lose money by attending some Michigan schools -- CMU not included -- proves her point.

"It's ridiculous for an organization to claim that students lose money earning a degree and would be better off never going to college. That defies logic and reality," she said.

Jeff Williams of Public Sector Consultants in Lansing, who studies educational data and statistics, noted that the PayScale study is based solely on the dollars returned, rather than on the return on investment percentage.

“There are universities (in the study) ranked above the University of Michigan simply because their dollar amount return on investment was higher,” he said. “But as a percent on what they spent, the return was lower … It’s a data point in a sea of data points.”

The PayScale study looked at overall income for graduates, and did not offer comparisons based on a graduate's choice of major.

“Definitely your major choice will play a role in the return you get, but this will at least give people an understanding of 'this is the typical return is of graduates from this school,’” said Bardaro. “Unless you go to one of the name-brand schools everyone’s familiar with, your major plays a much larger role than your actual school choice.”

For in-state students, the University of Michigan, Michigan State University and Michigan Tech rated most highly on return on investment, both on calculations considering financial aid support and without. In-state students at CMU faced a slightly negative ROI without financial aid, but a slightly positive one when financial aid was considered. (Editor's note: PayScale did not review the University of Michigan-Dearborn or U-M Flint.)

Richard Vedder, director of the Center for College Affordability & Productivity and a retired economics professor at Ohio University, said parents and students are poorly informed about the large numbers of students who drop out of college with lots of debt, or take six years to graduate, or fail to find a job with certain degrees. Nor do they know much about salaries one, five or 10 years after graduation.

"In order to calculate a return on investment, you have to know what the costs are, and what the benefits are," he said. "I'm a great believer in providing that information."

Vedder emphasized that additional learning, not necessarily college learning, is the proper course of action.

The high school valedictorian admitted to Harvard who will likely receive financial aid, graduate from college and get a good job is one thing, he explained.

"But we have more and more and more kids who won't graduate, or who'll get the janitor's job," he said. "I think most people need some kind of training after high school, but there's a big difference between spending six months at school learning how to drive an 18-wheel truck and spending four years in college."

Vedder says we’re in the midst of a higher education bubble. But, unlike the obvious and swift results of the housing bubble bust, this burst is disguised by heavy government subsidies to students.

"People can be sustained in college by student loans, Pell Grants and so forth for six years, even though the returns they're going to receive are dismal,” he said.

Tuition has skyrocketed in the past decade, and now 30 percent of adults have degrees (compared to 10 percent in 1970). That means fewer college graduates will find the traditional high-paying jobs that once went to those with degrees, Vedder said.

According to the Christian Science Monitor, 80,000 bartenders and 317,000 waiters and waitresses in the United States have college degrees, as do nearly a quarter of all retail salespersons. In all, 17 million Americans with college degrees are working at jobs that don’t require them.

Bridge archive: Michigan can't fit college grads into job slots

"We've reached a threshold now where the rate of return for many, many students has declined to the point where it is no longer automatically the right decision to go to college," Vedder said. "And that wasn't true 20 or 30 years ago."

PSC's Williams says, however, the averages show that college is a good deal.

"(N)ot all of us can be engineers; not all of us can be doctors,” he said. “Remember that the return is an average. Bill Gates dropped out of college. I completed college. Average us together and it still means you should go to college. There are a lot more of me than there are Bill Gates.”

Because any accreditation or degree after high school raises average lifetime earnings, Williams believes everyone should pursue some kind of higher education after high school.

“A college degree is as much about content as it is about process -- especially in this tough economy,” he said. “If you don’t come out of college with multiple skills, then you’re really in trouble in an economy that’s changing so fast, and is at a global level. You need to be flexible and able to adapt.”

Swanson, the Wayne State grad, believes a degree these days is “practically a necessity.”

“I know many who struggle to find jobs in all sorts of fields from education to engineering,” Swanson said. “They are very frustrated and understandably so, since they are probably thousands in debt.”

* Matt McLogan is a member of the Bridge Board of Advisers.

Jo Collins Mathis is a veteran journalist who has written for numerous publications in Washtenaw and Wayne counties. She was an award-winning reporter and columnist with the Ann Arbor News for 15 years, and a features page editor and columnist at the Ypsilanti Press.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!