A decade of slipping: Michigan's students fall behind

Michigan is falling behind other states in preparing its teenagers for college, a trend that could hobble the state’s efforts to revitalize its economy.

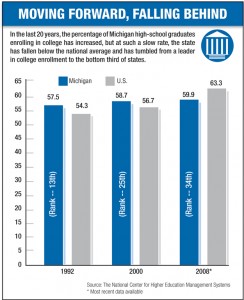

The percentage of Michigan high school graduates going to college has been inching upward, from 57.5 percent in 1992 to 59.4 percent in 2008, according to the National Center for Higher Education Management Systems. But many other states are increasing their college enrollment at a faster clip. Mississippi increased its college-going rate 16 percentage points; Minnesota shot up 15 percentage points; New Jersey, 11 percentage points.

Michigan dropped from having the 13th-highest rate of college enrollment in 1992, to 25th in 2000, to 34th in 2008, the most recent year available.

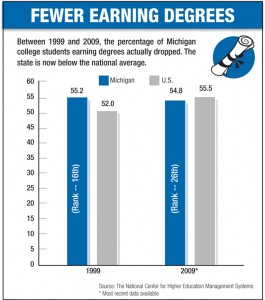

That lagging performance continues once Michigan kids get to college. The percentage of students who enroll in a public or private four-year university and earn a bachelor’s degree within six years (54.8 percent in 2009) is rising, but at a much slower pace than in most states. The state’s rank has fallen from 16th to 26th in a decade.

(Gov. Rick Snyder’s education dashboard shows a slightly higher six-year graduation rate, because the state data only includes graduation rates of Michigan’s 15 public universities.)

The story is even worse at Michigan’s community colleges. They rank 44th in the nation in the percentage of students earning an associate’s degree within three years. One in five Michigan students earned an associate’s degree in three years in 1999; A decade later, with more jobs requiring a degree, only one in six earned an associate’s.

At a time when a college education is practically a prerequisite to the middle class, the state-by-state data offers a sobering view of Michigan’s efforts to increase the percentage of residents holding a degree.

"If that trend sustains over time,” warns Larry Good, president of the Corporation for a Skilled Workforce, “we’ll continue on a path to becoming a poorer state.”

Experts: state must improve, or else

Michigan lost about 800,000 jobs in the past decade. A Bridge Magazine analysis projected that seven out of 10 jobs added to the Michigan economy between 2008 and 2018 will require some post-high school education. More than 37 percent will require a bachelor’s degree or more, compared to 29 percent today.

Yet the state has made bafflingly little progress increasing college readiness and attainment. The chances of a Michigan ninth-grader entering college by age 19 increased 1.5 percentage points between 1992 and 2008 -- one-quarter of the national rate of increase. By contrast, South Carolina increased 12 percentage points; Ohio, 9 percentage points; Indiana, 8 percentage points.

"There’s a tremendous economic loss in productivity and potential creation of jobs,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of Education Trust Midwest, an Ann Arbor-based research and advocacy group. “But there’s also a loss of human potential. We’ve got kids not realizing the full potential of their talent. It’s tragic when talented young people don’t get a chance to pursue their dreams.”

In 2008, about 42 percent of ninth-graders enrolled in college by age 19, ranking the state 34th in the nation (it was 22nd in 1992). The national leader was North Dakota, at 59 percent.

It’s as if Michigan is traveling on a freeway at 20 miles per hour, with other states zooming past at 70. And those other states are Michigan’s competition for new business and jobs, which tend to move to states with higher levels of education.

“There’s a direct correlation between educational attainment and good-paying jobs,” Good said. “If Michigan is moving slower, it puts us at a disadvantage.”

Lou Glazer, president of Michigan Future, says the rankings are indicative policy and culture. “We’ve gone through at least a decade in which policymakers have chosen tax cuts over education as a priority,” said Glazer, whose group pushes for a greater focus on higher education. “I don’t see the current Legislature making (education) a higher priority.

“Culture matters in this, too,” Glazer added. “Michigan is still one of the places having the hardest time embracing an understanding that economic success is increasingly driven by a college degree.”

Good believes it is more difficult to “move the needle” on college attainment today because many baby boomers with college degrees are nearing retirement. “Thirty years ago, most of the people who were retiring didn’t have a college degree,” Good said. “Now, (more) do. So you not only have to replace them, but you have to increase the number with college degrees. We can’t keep moving up the educational attainment rate unless we do something extraordinary.”

That can only happen with greater college readiness.

Compared to other states, Michigan schools have a less coordinated answer as to what being “college ready” means, and how to measure it, Arellano said.

Good agreed, pointing to states such as Illinois, Minnesota and Oklahoma, where leaders had made college readiness the centerpiece of economic programs.

“If I look at Midwestern states that are (increasing college attainment), in every state, there is a major commitment from the governor to the colleges,” Good said. “In Illinois, the lieutenant governor runs the effort. We’re behind the curve because we aren’t focusing on this as an economic imperative like other states.”

“We are definitely advocates of putting more money into things we know work,” Arellano said. “But it’s not always about money. It’s mostly a matter of policy and leadership.”

Arellano points to Massachusetts as a state where “They’ve made really wise decisions. Their kids really benefit.”

Massachusetts has among the highest standardized test scores in the nation, along with high college enrollment and degree attainment. But next-door neighbor Ohio also has made huge strides, passing Michigan in college enrollment and degree attainment in the past decade.

“Michigan has had just as many blue ribbon papers as any other state, but we haven’t seen the policy commitment,” Good said. “No one’s arguing it’s not important,” Good said, “but nobody is pulling it all together.”

“Just because it’s not happening here,” Arellano said, “doesn’t mean it can’t be done.”

Senior Writer Ron French joined Bridge in 2011 after having won more than 40 national and state journalism awards since he joined the Detroit News in 1995. French has a long track record of uncovering emerging issues and changing the public policy debate through his work. In 2006, he foretold the coming crisis in the auto industry in a special report detailing how worker health-care costs threatened to bankrupt General Motors.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!