Do charters skim profit, or spend smarter?

When Vickie Markavitch discusses the finances of traditional public schools vs. charter schools, she starts with a table of expenses, taking care to note the figures her analysis uses come from the state Senate Fiscal Agency, a reliable, nonpartisan source.

Then the superintendent of the Oakland Intermediate School District starts her rundown. The per-pupil state funding allowance is an average of what schools spend, she says, “and third grade doesn’t cost as much, high school needs more.” It’s also comprehensive for all programs, i.e., education plus co-curricular activities like band, athletics, etc., “which don’t come cheap.”

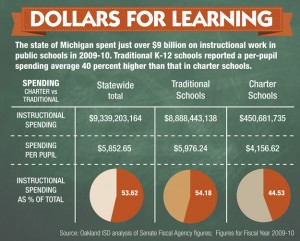

Most charter schools in Michigan are K-8, where costs are lower. They tend to be small, cater to niches and don’t offer comprehensive education, Markavitch says. They serve fewer students with special needs, and the ones they serve tend to have less serious hurdles to overcome. It all adds up, Markavitch claims, to charters spending, on average, $1,300 less per pupil than traditional schools. This is money that districts like the ones in Oakland County desperately need, she argues.

When Bob Lombardi discusses the same topic, he tells a different story. When the Flagstaff, Ariz., school he runs, Northland Prep, was expanding, they built a new building with 14 classrooms. The school’s board authorized Lombardi to spend $80,000 to outfit it. He spent $298, $2 short of the size of his petty-cash fund. He did it by shopping surplus sales at nearby Northern Arizona University, going through desks being discarded in refurbishments, cherry-picking the best and hauling them away himself on a rented flatbed. All-in, he estimates his final cost at 50 cents per desk.

For his teachers, he bought a trailer-load of discarded Steelcase desks, disassembled them and put them back together -- using undamaged legs from one, drawers from another -- and sent the discarded parts to a recycling center as scrap metal (for which he was paid). He figures each one cost $4.50.

For his teachers, he bought a trailer-load of discarded Steelcase desks, disassembled them and put them back together -- using undamaged legs from one, drawers from another -- and sent the discarded parts to a recycling center as scrap metal (for which he was paid). He figures each one cost $4.50.

He did the same with chairs, filing cabinets and bookcases, rolling up his sleeves to take damaged arms off otherwise perfectly acceptable office furniture, giving it new life. With the money he saved, he was able to buy overhead-mounted projection systems for classrooms, retrofit his building's lighting and -- most important -- give his teachers 3 percent raises and even a Christmas bonus.

The two anecdotes illustrate the best and worst of charter-school finances. To Markavitch, charters are like health-insurance companies that will only insure young, healthy people who don’t require much care. To Lombardi, they are a place where personal initiative, nimbleness and adaptability can flourish, bypassing stodgy bureaucracies and putting resources where they’re most needed.

To some extent, both are correct.

It's pronounced 'mip-sers'

Markavitch, in running down her numbers, says repeatedly that she doesn’t dislike charters. But as an administrator in a publicly funded district, she thinks they need to play by some new rules -- for the good of the entire system, both charters and traditional schools (which she prefers to call “community-governed”).

Markavitch, in running down her numbers, says repeatedly that she doesn’t dislike charters. But as an administrator in a publicly funded district, she thinks they need to play by some new rules -- for the good of the entire system, both charters and traditional schools (which she prefers to call “community-governed”).

With recent reforms in the Michigan Public School Employees Retirement System -- MPSERS -- she said it’s high time for charters, which have been exempt from paying into the system, to start. With every pupil who leaves his local public school for a charter, the burden on the former is increased, as fewer teachers pay into the system.

MPSERS provides pension and health-care benefits for retired employees, supported by contributions made by current employees and by individual school districts. The amount districts pay has risen sharply in recent years as health-care costs and unfunded pension liabilities have risen. Recent reforms now require new school employees to contribute to a hybrid defined-benefit/contribution plan, but the vast majority of members still are in defined-benefit plans.

“Public school academies get state money, they want to be called state schools, then they should be in the MPSERS program,” she said. “Either get rid of MPSERS entirely or require them to get in. If they were paying their share, we wouldn’t be paying $900 (per pupil). You don’t get the average unless you spend the average.”

According to the Michigan Association of Public School Academies, there are about 5,000 teachers in charter schools. Of those, about 1,150 are part of the MPSERS program. Some charters pay into MPSERS, "usually for employees hired who already have time in the system and want to continue to earn retirement under the system." Other charters offer portable 401(k) plans for their employees.

Lombardi, out in Flagstaff, doesn’t have much to say about retirement accounts. (In Arizona, both charter and traditional-school teachers pay into the state’s retirement system.) But as a veteran of traditional K-12 education, he remembers what it would have taken him to outfit his school under a former employer – competitive bids, approved vendors, and at least $50,000, he said.

“It wouldn’t allow me to do it this way,” he said, chuckling over his school full of bargains. “In the public-school system, we spent so much money, and some ended up wasted. It’s a joy to have rules that allow me to operate not only as a school, but as a small business.”

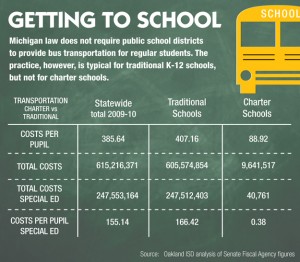

In some ways, this is an apples-oranges comparison. But it neatly encapsulates the argument over charter finances. Markavitch claims charters are getting too much of a free ride in the name of promoting innovation in education. Very few provide transportation and most don’t take the most challenged special-ed students, she says. In Oakland County, special ed costs $15,478 per services-receiving pupil; charters spent $5,282, Markavitch said.

Quisenberry counters the difference in special-ed students isn't as great, pointing to 2008 figures from the Michigan Department of Education that found "virtually no differences in proportions of students with different disability types between charters and traditionals." In the 2009-10 school year, state data shows just over 9 percent of charter students received some kind of special-ed services; in traditional schools, the figure was 14.4 percent.

Lombardi says that, free from the layers of bureaucracy and oversight, he is able to give his students and teachers the benefit of his bargain-hunting in the things that matter less in a quality education. His desks and chairs were put together like Frankenstein and are in '70s colors, but they’re clean and sturdy. Why can’t public schools be that smart about it?

“It’s fun to do this, because everything you save, you put into the kids,” said Lombardi.

Markavitch would settle for more transparency in spending.

“This is a movement to privatize public education,” she said. “I’m a capitalist, but not with public tax dollars. I’m not opposed to charter schools. But we need to make sure they're high quality before they open their doors. Parents should want our state to vet these schools well. The parents don't have time to do that.”

Professor on profit: $1,000 per student

Experts also say the profit factor is too murky for public dollars. Gary Miron, a Western Michigan University professor who has spent years studying charters, singles out National Heritage Academies as a company that has been enormously successful. With 44 schools in Michigan, more than any other state, they are making $1,000 in profit per student, per year, Miron said.

“As a private company, NHA does not disclose financial information,” said Joe DiBenedetto, spokesman for the company. “Given the structure of our management agreements with the school boards that have hired us and the multi-million upfront investment NHA makes with each school, we do not expect to make a profit over the term of the initial five-year charter the schools receive. For our average school, it will take up to 10 years to recoup that investment.”

Charter schools, like traditional public schools, receive a set "foundation grant" from the state to operate for each student they enroll. The amount matches the grant to the traditional public school district in which the charter operates or $7,110, whichever is lower.

To Dan Quisenberry, president of MAPSA, the arguments about supporting the state’s burdensome retirement program for teachers don’t carry much weight.

“State funding is really about educating kids, not sustaining our systems in Michigan,” he said.

He and Markavitch know one another, and both acknowledge respect for the other. They both agree that education in Michigan needs to improve.

“We can’t say we need to do the same things better, through the same systems. I'd argue that's impossible," Quisenberry said. "The only way you change things is to introduce dramatic differences, and that’s what charters are.

“I’m a believer in the invisible hand of the market. The more opportunities that are out there, inevitably we will improve things.”

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!