Grading teachers proves harder than thought

An annual performance review -- in which duties, accomplishments and expectations are weighed against a set of standards -- is a rite of passage for most Michiganians. And it's easy to do for, say, a car salesman. How many cars you sell? How much money did you make?

But for Michigan teachers, assessing performance and outcomes is proving anything but easy.

The Michigan Council for Educator Effectiveness, established in 2011, is charged with establishing “a fair, transparent, and feasible evaluation system for teachers and school administrators,” according to their vision statement, a system “based on rigorous standards of professional practice and of measurement.”

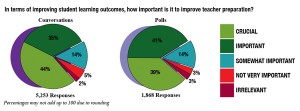

The public, in large part, agrees.

According to survey results in a new report, “The Public’s Agenda on Public Education,” released this week by the nonprofit Center for Michigan*, large majorities of more than 7,000 Michigan residents consulted via townhall meetings and scientific opinion polls said they want to increase accountability for teachers, while giving them greater professional support and training.

As a participant in a CFM community conversation in the Lansing suburb of Haslett put it, “Accountability is crucial because there is no profession where people are not held accountable. If you don’t hit the objectives then a closer look can be taken to see what is going on. Without accountability then the oldest teacher wins and the new good teachers get pigeonholed.”

All of which sounds simple. It’s coming up with that fair, transparent and feasible evaluation system that gets complicated.

“From our very first meetings, we’ve been trying not to be naive about this,” said Mark Reckase, a professor of education at Michigan State University serving on the MCEE. “We knew it wouldn’t be simple.”

The MCEE expects to make its recommendations by this summer, more than a year past its original deadline.

Groups involved in the same work in other states are having equal difficulty. A pilot teacher-evaluation program in Georgia produced results with less than 1 percent of teachers rated as ineffective, a black eye for a project that has educators and administrators alike struggling with how to get it right. And last year, the first in which Michigan ranked all its educators, the effort came up with similarly lopsided results.

“You’re dealing with people,” said Martha Ann Todd, associate superintendent for teacher and leader effectiveness in the Georgia Department of Education. “It’s part art and part science. But there’s a strong research base that tell us there are specific things we can do to improve outcomes.”

Most teacher-evaluation models are broken into two parts. One is based on observation by a senior administrator, who will sit in a class and watch a teacher at work, ideally on more than one occasion, and grade their performance on a variety of metrics – classroom management, explanation of material, planning and preparation. etc. Several systems are already in use in many school districts, and the MCEE is evaluating them for effectiveness.

The other half is student achievement – how well students progress through the term under a given teacher. And as subjective as observation by one educator of another can be, student-achievement progress is even thornier. Students progress at different rates, and are influenced by myriad factors outside a teacher’s control, from nutrition to home environment to how well he or she may have slept the night before a test.

Will such a system be unfair to those who teach disadvantaged students? How to judge student progress in areas ranging from art to music to mathematics to social studies?

Add to that the fact that this sort of measurement of teachers is relatively new, and the delays and difficulties come into focus.

“The reason there are a lot (of methodologies) is, people are trying to make adjustments for the group of students assigned to a teacher. It’s far from random,” Reckase said. “There are all kinds of influences on how students achieve, and no one really knows the best way to do this,” said Reckase.

Traditionally, teachers are rewarded for seniority and education; more master’s degrees are awarded in education than any other field, and teachers with graduate degrees will watch their salaries rise with each one. But Deborah Loewenberg Ball, dean of the University of Michigan’s School of Education and chair of the MCEE, says there’s no real link between a teacher’s level of education and better teaching.

“What the data show is that the current (degree) offerings increase knowledge and perspective (among teachers), but not necessarily student achievement,” Ball said.

What makes better teachers, Ball said, is training and feedback for improvement, and that’s what the new measurement models are trying to put in place.

The aim, Todd said, is not necessarily to identify incompetent teachers, but to help those with the potential to improve to do so.

“We’re behind on our timetable, too,” Todd said of the Georgia program. “This is huge, challenging work in so many ways, but it’s such worthwhile work. There’s no question in my mind that working on this is the right thing to do.”

Reckase suggested the American culture surrounding education could use an adjustment, too. Teachers – and teacher unions – make easy targets for critics of American schools, but in other countries, attitudes toward educators are quite different.

“In Taiwan, teachers and school administrators go to residential professional development every summer, for a number of weeks,” to compare theory and practice and share experience,” Reckase said.

“But that’s hard to bottle and transport.”

*The Center for Michigan is the parent organization of Bridge Magazine.

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!