Michigan wants Lansing, schools to lead on college affordability

Michigan was known as the birthplace of the middle class, a place where anyone willing to work hard could not only get by, but prosper. A high-school diploma was enough to get a well-paying job in hundreds of blue-collar workplaces.

But the turn of the millennium brought a reckoning. Now, finishing high school is only the beginning. People seeking a solid career, even in manufacturing, need at least some advanced training beyond high school.

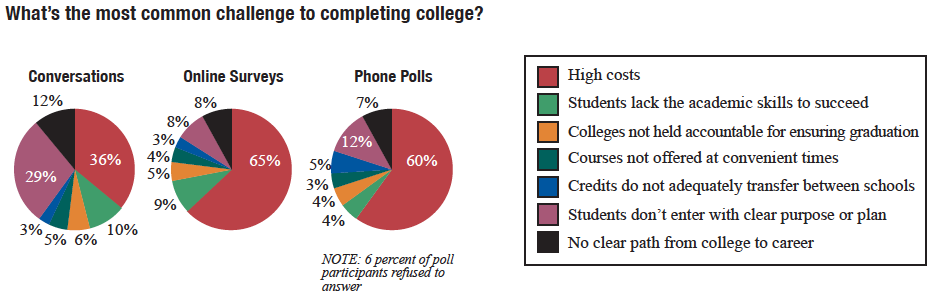

More than 80 percent of participants in The Center for Michigan’s Community Conversations this year said a college degree or other vocational training is important or very important to prosper in the modern economy.

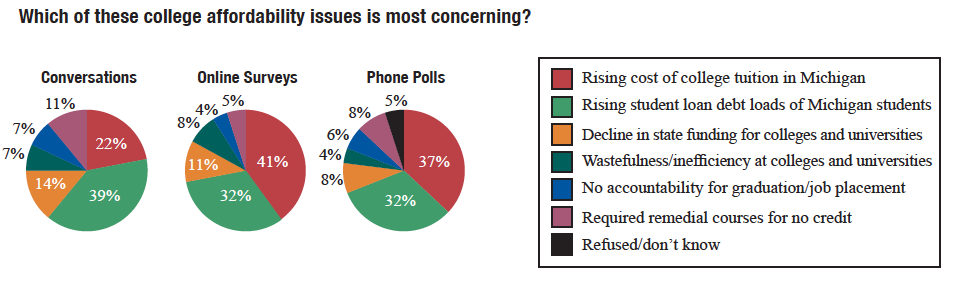

But the ever-climbing cost of college makes the majority of people surveyed – about 55 percent – question whether families can afford higher education, and even whether the expense is worth it. Participants said that both the Legislature and schools must share blame for the burden college costs place on Michigan families.

MORE COVERAGE: Residents like these programs to reduce college costs

Participants in the Center’s “Getting to Work: The public’s agenda for improving career navigation, college affordability, and upward mobility in Michigan,” campaign – more than 5,000 statewide, asked in live conversations and in phone and online panels and polling – wrestled with the conundrum over and over: Student-loan debt saddles young adults with a financial burden at the time in their careers when they could be saving money, while buying cars, houses and other big-ticket items that help drive the economy.

“We should allow them to hit the ground running,” one participant said of young graduates.

Student debt is “another kind of slavery,” said another.

As Bridge has reported, the cost of a traditional four-year degree has more than doubled in a generation, from an inflation-adjusted $7,938 a year in 1975 to $18,943 annually in 2014. But agreement on how to rein in ever-rising tuition and limiting loans is harder to come by.

More than 80 percent across all three of the Center's survey methods said state government should fund public colleges and universities at higher levels to make college more affordable. And more than 90 percent of poll and online survey participants said public universities need to become more cost efficient, a view held by 80 percent of Community Conversations participants.

When asked who was most responsible for improving college affordability, residents were split, with a slightly higher number putting the blame on Lansing. The most common response was state government (47 percent in polls and surveys and 52 percent in Community Conversations). The second most common response was colleges and universities themselves (44 percent in polls and surveys and 41 percent in Community Conversations).

In the 2001-02 academic year, Michigan public universities got about 48 percent of their budgets from state support. By 2013-14, that share had dropped to 21.5 percent, according to the state’s House Fiscal Agency. Other costs connected to higher ed have gone up, at the same time scholarships have dried up.

More than 80 percent of Michigan residents interviewed by the Center agreed that public colleges and universities could and should become more cost-efficient. A return on the steep investment college requires is, increasingly, an expectation of those surveyed. One parent put it this way: “When we visit college campuses, we always ask ‘What’s the job placement rate and how much do you have to do with that? Are you giving students internships?’ I’ll pay, but I don’t want the debt and no job for my kid.”

Requiring Lansing and the state’s colleges and universities to cooperate in lowering costs is complicated by their DNA; Michigan’s higher-ed institutions have constitutional autonomy from the legislature, at least in terms of how they are run. Lansing’s leverage is in controlling the amount of money in the state budget steered to schools. The legislature has made “tuition restraint” a string attached to portions of funding it has awarded for five years. Yet administrators at some schools, notably Wayne State in 2013 and Oakland University in 2015, have raised tuition well beyond Lansing-imposed limits, by 8.9 percent and 8.48 percent, respectively. (The caps were 3.75 percent and 3.2 percent in those years.) Both institutions forfeited state aid, but said the increased revenue from tuition increases was necessary after years of cuts in state appropriations.

Taming costs

Community Conversation participants have their own list of suggestions for reducing college costs (See accompanying article), some of which are shared by policymakers and administrators:

Reform the student-loan industry. Lower interest rates for education loans. (“My kids have an 8.5 percent interest rate on their loans. You can buy a car at a lower rate,” said one resident.) Take the banks out of the picture. (“The banking industry is a huge lobbying power that serves as a huge roadblock to student loan debt reform,” said another.)

Let students earn more college credit in high school. Advanced Placement classes, middle-college/dual-enrollment programs (which allow students to earn college credit while still enrolled in high school) and other initiatives help students bank early credits, free of charge, before they write their first check to a college bursar. “If you increase dual enrollment, it makes their post-high school opportunities cheaper, but you also have actual college experience. How you prepare for classes (and learn) what is it going to be like it puts you far ahead,” said a participant.

Increase enrollment at community colleges. These schools provide a low-cost entry into a four-year plan for those who eventually want to earn a bachelor’s degree, as well as those seeking a two-year or vocational degree. Cost per credit hour is lower at community colleges, making them attractive for students looking to take lower-level courses at a bargain price, despite some concern over whether all credits will transfer. “I went to community college and it gets your life going faster and earning more. I know that it works. I came out with no debt,” one said resident.

Rep. Joel Johnson, R-Clare, said “expanding our definition of ‘college’” will go a long way toward making post-secondary education easier to swallow. Certification programs for many careers don’t require four years, and some not even two. But they prepare students for skilled careers at very reasonable prices.

Johnson, chairman of the House Workforce and Talent Development Committee, said he also supports apprenticeship and internship programs, so-called “earn while you learn” opportunities. And better counseling while students are still in high school can guide them to career programs with good track records and solid prospects for employment.

The Purdue experiment

Many in higher education are watching Purdue University, in West Lafayette, Ind., as a model of how a large, four-year institution can cut costs without compromising academics. Led by former Indiana Gov. Mitch Daniels, hired by the university in 2013 after his second term ended, Daniels immediately imposed a tuition freeze that was recently extended through the 2016-17 academic year. Room and board costs have fallen by 5 percent, through “imposing efficiencies on food services,” said William Sullivan, treasurer and chief financial officer of the university. Flat tuition and falling room and board make for an overall decline in costs, a fact the university has boasted about nationwide.

By contrast, Michigan’s universities saw tuition rise an average of 3.62 percent just in the last year.

Purdue is also looking for a way to cut four-year degrees down to three, and Daniels has dangled a $500,000 bonus to the first department that comes up with one. It’s also opening a charter high school in Indianapolis to better prepare students for the rigor of college work in STEM fields. All of this is happening while state subsidies continue to fall. Sullivan said the administration is “looking under every doormat and behind every door, trying to think of ways to get more efficient,” as well as exploring corporate-style cost-sharing. A on-campus joint venture with Amazon, with what the university says is the online seller’s first brick-and-mortar store, gives students a discount on books, while returning royalties to the university.

“No nugget is too small,” Sullivan said. “If you go after enough (small cost cuts), pretty soon it adds up to a pretty big number.”

Purdue is a selective school, but even the selective ones shouldn’t be free of the mandate to control costs, said Dewayne Matthews, vice president of strategy development for the Lumina Foundation, an Indianapolis-based nonprofit working to increase higher-education attainment.

“It’s getting harder and harder, if not impossible, to simply pass on a fixed-cost framework to tuition-paying students,” said Matthews.

Lumina has been studying the cost question, and in August rolled out its Affordability Benchmark for Higher Education, seeking to define what is a reasonable investment by students.

Lumina wanted to know whether “it is actually possible to define or determine how much people can afford to pay for college,” Matthews said. The formula researchers came up with is that costs should be capped at 10-10-10: A family should save 10 percent of discretionary income, over 10 years, with students contributing by working 10 hours a week while enrolled. (Working more than 10 hours a week impedes academic progress, Matthews said.)

Obviously, that’s a different number for every family that calculates it, but Matthews notes this is the start of the discussion. The next job is to take it to policymakers and administrators, and compare how current institutions’ costs compare with, say, a median number.

At Purdue, Daniels has nudged the school toward a more business-oriented conversation, with emphasis on creating jobs, responding to workplace needs and return on investment for students. Such discussion can lead to philosophical questions of what the purpose of higher education is – mind-expander or trade school? Community Conversation gave this question considerable thought.

“What’s the point of college?” asked one. “Is the point of college exclusively to get a job, or is there a value at some level of having an informed citizenry with a well-rounded liberal arts education. I’m not suggesting one way or the other, there needs to be a balance of both. To know things other than your job is important.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Post-secondary education is as necessary to middle-class employment as high school was to previous generations. But many residents are now asking if the degree is worth the pricetag. (Photo by Light Brigading via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license)

Post-secondary education is as necessary to middle-class employment as high school was to previous generations. But many residents are now asking if the degree is worth the pricetag. (Photo by Light Brigading via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license) Graduating with a smile? Students with heavy loan debt may find the celebration short-lived. Participants in The Center for Michigan's Community Conversations say higher education is a must to join the middle class, but affordability is a real concern. (Photo by Bill Couch via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license)

Graduating with a smile? Students with heavy loan debt may find the celebration short-lived. Participants in The Center for Michigan's Community Conversations say higher education is a must to join the middle class, but affordability is a real concern. (Photo by Bill Couch via Flickr; used under Creative Commons license) click to enlarge

click to enlarge click to enlarge

click to enlarge