MLK’s dream not yet realized at college graduation – it’s not even close

Paulette Granberry Russell remembers walking on the sprawling campus of Michigan State University as a scared, under-prepared freshman.

“I was an African-American woman and first-generation (to attend college in her family),” she said. “I didn’t have the tools or the networks that would have made this an easier transition.”

Despite challenges, she earned a diploma, and eventually a job at MSU, where this week she can walk across campus and see minority students facing the same struggles she faced.

“I see myself in these students,” said Granberry Russell, director of the Office of Inclusion and Intercultural Initiatives at MSU. “I know what a difference it made for me to have access to higher education.”

Yet the diploma gap between black and white students is widening at MSU, as well as many campuses across Michigan.

At Michigan State University, a black-white gap that was a disheartening 18 percentage points in 2002 grew to 26 percentage points by 2011; Central Michigan’s gap more than tripled in a decade.

At Wayne State University, located in the nation’s largest African-American-majority city, white students are five times more likely to earn a bachelor’s degree than their black classmates. In 2010, one in 10 black students who’d enrolled at Wayne State six years earlier had earned a degree.

(See the black-white graduation gap for Michigan Universities)

A year later, the figure was one in 13 – one of the lowest African-American graduation rates in the nation.

Black college students aren’t the only ones hurt by the diploma gap. Granberry Russell calls it a “drain on the economy” for African-American students to not succeed in college. “We know there is untapped potential,” she said.

“Every major university is facing this challenge,” said Mark Jackson, director of the Upward Bound program at Eastern Michigan University, another school where the black-white graduation gap is higher than it was a decade ago. “It should be an indication of the magnitude of this problem.”

Moving more African-American students from freshman orientation to graduation ceremonies is a test Michigan can’t afford to fail. In a state that needs more college graduates to invigorate an increasingly high-tech economy, graduation rates — particularly for minorities — need to improve.

Yet the state, which makes overall graduation rates a performance funding measure for Michigan’s 15 public universities, doesn’t track the gap between white and minority degrees.

Brandy Johnson, executive director of Michigan College Access Network, thinks colleges need to pick up their game.

“Michigan has one of the highest college-enrollment rates among low-income students (in the U.S.),” Johnson said. “Bu they’re not completing college. It’s net positive. But we can’t use that as an excuse. We need to get them through (to a degree). We need to build the plane while we’re flying it.”

The racial graduation divide is stubbornly wide across the country. A gap that was 18 percentage points in 2006 (60 percent for whites compared to 42 percent for African-Americans) grew to 22 points in 2011 (62 percent to 40 percent).

Among the public universities with substantial minority enrollment, Wayne State had a 31 percentage point graduation gap; Oakland University, 26 points, and Central Michigan, 23 points. The University of Michigan made significant strides, narrowing the diploma gap in Ann Arbor from 22 percent in 2002 to 13 percent a decade later.

Among Michigan private colleges, Lawrence Tech had a troubling black-white graduation gap of 42 percent, with white students earning degrees at almost five times the rate of African-Americans. The rate is hard to statistically quantify on many private campuses because most of Michigan’s private universities don’t have substantial African-American enrollment.

Much of the challenge of closing the diploma gap starts long before students walk onto campus. On average, minority students tend to come from lower-income families and be less academically prepared for the rigors of universities. Nationally, a quarter of white high school graduates were considered fully academically prepared for college, according to the ACT’s annual report released in August; only five percent of black high school graduates were considered fully ready.

In 2005, the University of Michigan-Dearborn decided to try to attract valedictorians from high schools in surrounding counties. The result was a significantly higher African-American six-year graduation rate. The initiative was dropped the next year, and graduation rates slipped.

The point, made by Roma Heaney, director of institutional research at UM-Dearborn: graduation rates say more about who is coming in the door of the classroom, than they do about the classrooms themselves.

Johnson and her Michigan College Access Network understand the relationship between standardized test scores and college success. But keeping kids out of college who are at risk of dropping out is the wrong decision, even if lower graduation rates put universities in danger of losing state funds. A better response for the students, the schools, and the state, is to find ways to help those students stay in school, Johnson said.

UM-Dearborn offers scholarships to high-performing students in low-income communities to get kids on campus, then offers career counseling and African-American mentors from the faculty to keep them there.

Eastern Michigan University has a conditional enrollment program for academically iffy students, in which students are required to meet regularly with faculty and older students.

“Ultimately, you want to assist those black students to become good college students,” EMU’s Jackson said.

Some schools around the country have managed to erase the black-white graduation gap. A report by Education Trust points out that the University of North Carolina-Greensboro graduates African-American and white students at the same rate. That same report admonishes Michigan State University for having a black-white graduation gap of more than 15 percentage points every year for the past decade.

“There is a continuing trend of inequitable success outcomes at Michigan State University,” the report says.

While the gap is wide in East Lansing, Granberry Russell appropriately points out that MSU still graduates African-American students at a rate higher than the national average (55 percent earn a degree within six years, compared to 40 percent across the U.S.) “That’s not good enough,” said Granberry Russell. “We are continually assessing our efforts.”

MSU has a transition program for students entering college, and has moved some of its academic advisors to the residence halls. Some minority students “come out of high schools that have their own challenges,” Granberry Russell said. “But we believe they have the ability to succeed at Michigan State. When we admit a student to Michigan State, we have a responsibility to provide them with the support in able to persist, succeed and graduate.”

Looking at the statistics, Jackson knows there’s still a long way to go.

“If society is going to change,” he said, “it’s going to change with higher education.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

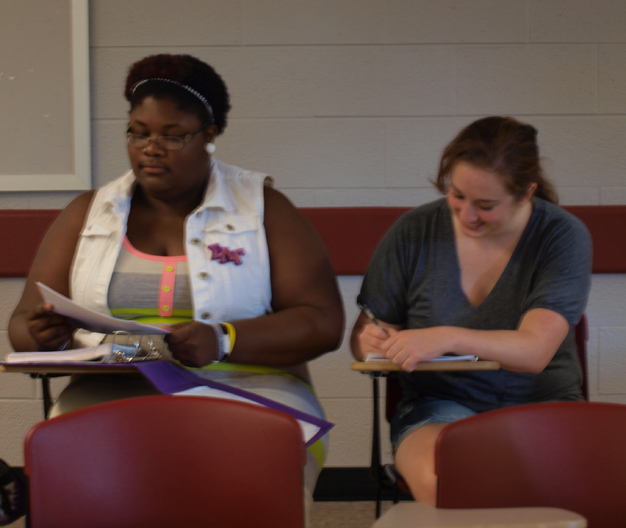

Why is one of these college students more likely to graduate than the other? Michigan colleges are struggling to figure it out. (Bridge photo by Monique Belser)

Why is one of these college students more likely to graduate than the other? Michigan colleges are struggling to figure it out. (Bridge photo by Monique Belser)