My school’s great, it’s Detroit that’s failing – and other myths

Since 2009, Detroit students have posted worst-in-the-nation test scores among large urban school districts, drawing unwanted attention that still dogs the city today.

But if people in Michigan think bad test scores are confined to poor students in big cities, they’re wrong.

“We can’t afford to take our time getting back to good (academic) health...Every single day that a child isn’t learning in the most effective way is a day lost, and another day that chips away at that child’s eventual ability to contribute to the state.” Elizabeth Moje, associate dean for research and community engagement at the University of Michigan School of Education.

In fourth and eighth-grade reading and math – key barometers of student learning – Michigan students of different races and income levels have fallen behind their demographic peers in other states, and the gaps are widening. Over the past decade, Michigan has been lapped by states as liberal as Massachusetts, as conservative as Tennessee, and as close as Indiana, Ohio and Wisconsin.

“I think everyone thinks it’s fine in their own school district, but it’s not,” said Doug Rothwell, president and CEO of Business Leaders for Michigan, an advocacy group comprised of top executives from the state’s largest companies and universities working to improve the state’s economy. “It’s a statewide problem.”

Which is why Bridge is launching a year-long examination of Michigan’s declining educational fortunes and what steps lawmakers, schools and others can take to improve student performance, including the study and adoption of policies proven to work elsewhere. Inaction will only compound the crisis.

“It’s embarrassing to be so far behind the other states in the Midwest and the nation and the world,” said Gary Naeyaert, executive director of the Great Lakes Education Project, which advocates for public school academies and education choice in Michigan.

In a state with some of the nation’s best public universities, less than a third of fourth graders are proficient in reading, and less than a third of eighth graders are proficient in math, according to the 2013 National Assessment of Educational Progress, which compares student performance across the country. But the problem extends across a wide cross-section of the state’s demography. Consider:

- In fourth grade math, Michigan’s white students tied for seventh on the NAEP in 2003. Ten years later, they tied for 35th.

- African-American students in Michigan ranked 26th in 4th-grade math 2003. In 2013, they were tied for last in the nation among the 44 states with reported NAEP scores.

- In fourth-grade reading, Michigan students who are not from low-income families fell from a national rank of seventh in 2003 to 27th in 2013.

- Eighth-grade math students in the 75th percentile of academic performance in Michigan – in other words, those considered above-average -- were ranked 9th in 2003 when compared with above-average students in other states. A decade later they had fallen to 30th.

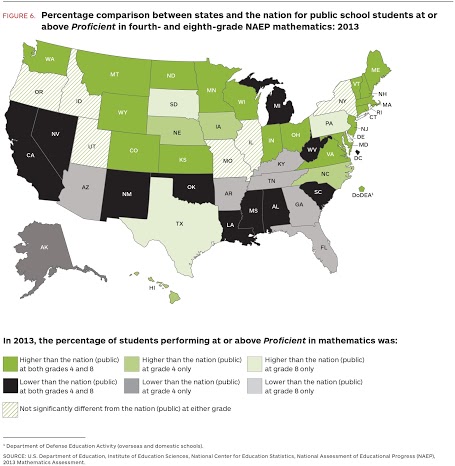

Michigan hasn’t always been near the bottom. A decade ago, Michigan’s fourth graders were bested by only 11 other states in math. By last year, Michigan was looking up at 35 states, statistically beating out only students in Alabama, New Mexico, Louisiana and Mississippi.

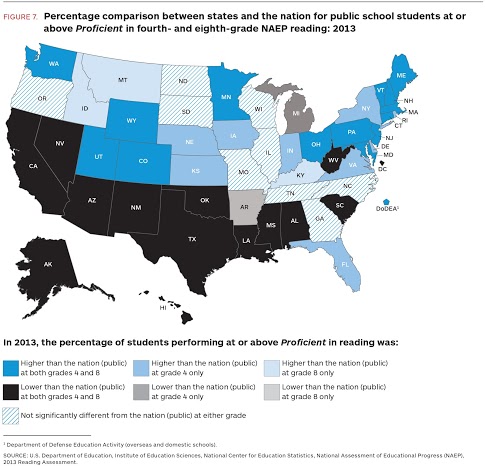

Michigan is now one of only two states (West Virginia is the other) north of the Mason-Dixon line whose students fell below the national average considered “proficient” in math for both fourth and eighth graders in 2013.

It’s the kind of news that can turn a room of business leaders in West Michigan numb.

“People gasp. There’s silence,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of the nonprofit Education Trust-Midwest, describing such a meeting where Michigan’s rankings were presented. “It was almost like being at a funeral.”

No one wants to bury the state just yet, and many in Lansing are working on a host of changes that could improve education in Michigan. But Arellano, Rothwell, Naeyaert and others said they are fearful what will happen if the state does not make changes like improving teacher quality, helping struggling students get help early, and ensuring Michigan students can compete with students across the nation and around the world.

Economy needs prepared students

Michigan’s political and business leaders have long warned that the low-skilled factory jobs of years past are vanishing, and high school graduates need some kind of education – either post-secondary training or a two- or four-year college degree – to fill the more demanding, higher-tech jobs of the future.

But national and state data show many of Michigan’s students may be unprepared.

“Michigan now ranks well below the national public average on every grade and subject and for virtually every subgroup across all four tests of national assessment,” said Sarah Lenhoff, director of policy and research for Ed Trust-Midwest, which published its latest report, “Stalled to Soaring: Michigan’s Path to Educational Recovery,” today.

In addition to pointing out the problems – Michigan was, for instance, one of only six states to post lower scores in 2013 than a decade earlier in fourth-grade reading – Ed Trust-Midwest’s report looks to Massachusetts and Tennessee for potential solutions.

In Massachusetts, once known as much for its textile plants as its clam chowder, the state has spent the past 20 years adopting tougher academic standards, increasing teacher training, targeting funding to poor schools and creating a high-quality charter school system, according to Ed Trust-Midwest.

Tennessee invested early in higher academic standards and a more comprehensive system for evaluating teachers, and implemented Common Core curriculum standards in phases.

Results in both states have been impressive.

In fourth-grade math, Massachusetts students, already among the top performers in 2003, saw its score rise from 242 to 253 in 2013. Over the same decade, Tennessee went from 228 to 240. By contrast, Michigan inched from 236 to 237, a statistical standstill, over that same period.

Tennessee recorded some of the biggest NAEP gains in the country in 2013 and its African-American students, once on par with Michigan’s, are now substantially ahead. Ed Trust-Midwest estimates that African-American fourth-grade math students in Tennessee are now half a year ahead of African-American students in Michigan.

A challenge for Lansing

Among those most concerned about Michigan student performance are educators who worry what could happen in the state if it doesn’t solve its education woes.

“We can’t afford to take our time getting back to good (academic) health,” said Elizabeth Moje, associate dean for research and community engagement at the University of Michigan School of Education. “These children are our future. And every single day that a child isn’t learning in the most effective way is a day lost, and another day that chips away at that child’s eventual ability to contribute to the state.”

Which puts the burden back on Lansing, which has passed myriad education reforms over the past three years, many of them controversial, including measures that lifted a cap on charter schools in the state and tied teacher tenure and evaluation to student test scores. Lawmakers are now considering changes in the way public schools are funded, and how to best implement a statewide teacher evaluation system and the Common Core, rigorous curriculum standards that have been adopted by 44 states.

Rothwell said it’s imperative that Michigan’s leaders implement Common Core and tests that are aligned to the new standards, which would allow parents across Michigan to compare how their children and schools perform compare with students and schools across the country. But adopting the last stages of Common Core have hit a roadblock, with a growing chorus of critics saying the standards will take away local control.

Though many agree the state’s education system is in crisis, finding the appropriate solution continues to be difficult. Michigan lawmakers, educators and interest groups continue to clash over everything from school funding formulas to graduation standards, charter school expansion and how to best close the state’s yawning achievement gap that leaves low-income students and children of color far behind their white, more affluent classmates.

And finding a solution that requires more spending may prove difficult in a state that’s just coming out of the Great Recession and has cut billions of dollars from state and local budgets.

"I think there's a crisis of performance and lack of growth,” said John Austin, president of the state Board of Education. “There's also a crisis of schools being able to deliver good education and run programs,” he said, pointing out nearly four dozen districts are running deficits and two-thirds of districts and a third of public charter schools face declining enrollment.

"The whole system is under stress and not performing. We need to get our heads around what's broke and how do we fix it."

Naeyaert, of GLEP, recognizes that lawmakers may lack the “stomach” to raise taxes. But he said that’s not necessarily the solution anyway. His organization has called for changes in how the state allocates funding. He said school choice must remain in Michigan and that the state should reward programs that succeed -- and punish those that don’t.

While GLEP may be at odds with Austin and others on funding strategies, Naeyaert said there is agreement that state residents should pay as much attention to poor test scores as they are now paying to poor roads. “I think the start of any conversation has to start with what’s happening in the classroom.” he said.

Business and political leaders have contended for nearly a decade that education is the salve to the state’s unprecedented decline in income To get there, everyone will have to support education policies that are proven to help students, not only in individual communities but across Michigan, experts say. Bridge will highlight many of those initiatives, some in Michigan, some elsewhere, in future reports.

“Does it matter to me that the kids in the county next to me are doing well? It should,” said Karen McPhee, superintendent of the Ottawa Intermediate School District. “We all live in an economic reality larger than ourselves. We have to be in the business of educating the whole state.”

Senior Bridge staff writer Ron French contributed.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!