One Dearborn school soars. Another stumbles. Why?

(Today’s stories are the first of two parts on gaps within school districts. Part 2 runs next week)

DEARBORN – There are few places more colorful and heartwarming than an elementary school that is clicking on all cylinders, and Geer Park Elementary in Dearborn is doing exactly that. On a recent visit before summer break, adorable children moved through the halls, many of the girls in hijabs, the most obvious visual clue that this is a school where two-thirds of students speak Arabic at home and English as a second language.

You wouldn’t know it from a glance at their most recent MEAP test scores. While many English language learners struggle in early grades, 67 percent of Geer Park third graders met or exceeded state standards in reading in the most recent state data, 6 points above the state average. What’s more, most of those students come from economically disadvantaged homes – 80 percent, making the achievement that much more impressive. Geer Park’s ability to overcome poverty and language gaps led to the school being ranked 6th out of 1,210 elementaries statewide in Bridge’s Academic State Champs analysis this year.

Across town, Lindbergh Elementary also shows every sign of thriving, and by many measures it is. Walls are plastered with student work and classrooms buzzed with activity in the last weeks of the school year. On the second floor, parent volunteers set up a refreshment station for third-graders taking the first day of state tests in English language arts.

According to everything we know about education statistics, they should outscore the students at Geer Park. Only about a third of the Lindbergh student body are economically disadvantaged, and about a quarter are classified as English language learners. But Lindbergh’s 2013-14 scores on third-grade reading tests were 13 points below Geer Park’s, and seven points below the state average.

The school is doing well in other areas; in third-grade math, its scores are above the state average. And in later grades, Lindbergh students perform well above both the state average and those students at Geer Park. But at a time when state policymakers are considering making third-grade reading scores a critical measure of early literacy, schools can ill afford a disappointing showing, even if their students are performing well otherwise, as are the students at Lindbergh.

Jill Chochol, associate superintendent for elementary education in Dearborn Public Schools, has a simple answer when asked her opinion for the third-grade reading score discrepancies at the two schools:

“I don’t know.”

High stakes, murky causes

Across the country, data has never been so important in public education. Depending on the state and its policies, test scores and other measurements of student learning may be tied to school funding, teacher salaries and evaluation and administration; Michigan’s Education Achievement Authority was created by Gov. Rick Snyder in 2011 to turn around failing schools, based largely on their abysmal test scores. Parents check district test scores when shopping for housing, and good scores can drive property values higher.

But drill down to the school level, and test scores can sometimes be like pressing one’s nose to a pointillist painting – a lot of dots that critics say don’t necessarily make a clear picture.

MORE COVERAGE: Grand Rapids cites the limits of state rankings to explain school gaps

Why did Geer Park, with a higher percentage of students living in poverty and greater language challenges, have such high scores? The principal is dedicated, the teachers likewise. There’s extra help for students who need it, constant reinforcement of best-practice techniques and parent buy-in.

Why were Lindbergh’s scores so far below? That school’s principal and faculty are also dedicated. Like other educators in Dearborn, they have data on individual students, and know who needs extra help, and see that they get it. They, too, follow the curriculum closely and their parental support is as high as anywhere in the district.

There were new students at Lindbergh from outside the district in the 2013-14 school year, the year these tests were taken, these scores were recorded; were they less prepared than the children who started there in kindergarten? Was there a curveball on the test itself? Chochol, the assistant superintendent, recalls that the district had been using primarily information-based texts in lessons, and that year, a test section on poetry took them by surprise. But both schools had the same surprise.

Or was it just a bad year at Lindbergh? This year, on the first day of M-STEP testing (which replaced the MEAP), a third-grader sat miserably in Lindbergh Principal Pam DeNeen’s office, a wastebasket beside her, in case her nausea bubbled over. Her nerves had gotten the best of her, and it was an open question whether she’d go back to class and pick up her pencil again, or retake it on a makeup day. One girl shouldn’t tip the balance, but add four or five more, and it could be enough to account for a disappointing collective result at Lindbergh, DeNeen said.

Neither DeNeen nor Lamis Srour, her counterpart at Geer Park, take special credit for their schools’ success. And neither can explain the discrepancies, not the ones in third-grade reading, or a more puzzling one: The next two grade levels, in fourth and fifth grade reading, show Lindbergh students consistently improving, while Geer Park pupils level out. Lindbergh fifth-graders outscored Geer Park’s by 25 points in reading; its fourth-graders, by 13 points.

Challenges of all kinds

Dearborn has been well-known for decades as a magnet for immigrants from the Middle East, and Geer Park has children who are both newly arrived or are the American-born children of less-recent newcomers from Lebanon, Iraq, Yemen, Saudi Arabia and other Arabic-speaking countries. In general, teachers and principals say, these parents are eager for their children to succeed in their adopted home, and support educators.

Srour does not romanticize her student body. She has a lot in common with them as the American-born daughter of Lebanese immigrants, and she knows the challenges that many of them face.

“Dearborn has the same situations you find in other cities,” she said, ticking off a few. “Single parents, divorce, children being raised by grandparents. The only thing exceptional is, we have more multi-generation homes.”

In those homes, most of these children will hear their parents and grandparents speaking Arabic or perhaps a mixture of Arabic and English. With a young child’s talent for absorbing new languages, they may well speak English fairly well when they arrive for kindergarten, but have other gaps in their knowledge – not knowing the alphabet, for instance. Language competency has four parts – speaking, listening, writing and reading. Almost all English learners, or ELs, will need extra help in one or more parts.

Geer Park teachers, Srour said, treat every student as an EL, “because they are.”

“You have to be very thoughtful about how your day looks and the lesson plan,” she said. Balancing those four components throughout the teaching day is essential, as is weaving them into other subject areas. A lesson on turtles might be developed into an opportunity for learning about language, science, social studies, art and reading.

Third-grade reading skills are considered an essential benchmark because beginning in fourth grade, the work is less about “learning to read” and more about “reading to learn,” i.e., navigating instructional texts. And, Choquol said, research shows that students who aren’t at grade level in reading by the end of third grade face steep odds of catching up. Because children from economically disadvantaged homes are more likely to be left behind, Geer Park concentrates on getting them caught up.

There are 12 summer-school slots per grade level at Geer Park, and the school’s library is open two days a week during those months. Some recent immigrants will return to their native countries for long visits during the school year. When children leave, parents and teachers meet beforehand, lesson packets are provided in advance, and a contingency letter goes into the file, laying out the expectations.

“Holding everyone accountable helps,” said Srour.

To be sure, all over the school, students routinely make remarkable progress. In one kindergarten class, a boy named Hassan worked in a small group with Mary Timpf, an instructional coach. She asked the children to spell a few simple words, using plastic letters on a board. Hassan whipped through them easily, despite having arrived in the U.S. just last October, with “not a word” of English in his vocabulary, Srour said.

Across town, a culture of learning

At Lindbergh, the challenges are different. The student body is better off economically, more likely to be speaking English at home with educated parents, and also more likely to be in stable homes. But the economic upheaval that rocked Michigan didn’t spare any part of Dearborn, DeNeen said, noting that when she came to the school 12 years ago, 98 percent of students stayed in the school from kindergarten through fifth grade; today that’s dropped to half as the city has absorbed the housing market’s instability and families move more often. The school’s economically disadvantaged population was once 3 percent, and now it’s 29 percent.

But in general, Lindbergh has all the hallmarks of a thriving, rigorous school. It has the highest parental participation rate in the district. In one classroom, a teacher shows off the pop-bottle rockets students made under the direction of a classmate’s father, an engineer, who is a participant in the Watch D.O.G.S. program, or “dads of great students.” In the fall, parents put on a “haunted school” attraction, in the spring, a fun fair to celebrate the end of the year.

“Parents here take their kids places,” said DeNeen. “They take them to (the Eastern Market’s) flower day, to places that make them well-rounded.” All of it is likely to produce capable learners.

In Jennifer Knaus’ fourth-grade classroom, she reads “Rump: The True Story of Rumpelstiltskin” aloud to the class, stopping often to ask questions about vocabulary, or to clarify a plot point. The students are engaged in both the story and the lesson, stabbing their hands in the air to answer Knaus’ questions.

Emily Blumenstein was one of the mothers passing out refreshments to third-grade test-takers, a group that included her son. Blumenstein and her husband both have master’s degrees ‒ she’s a psychotherapist, he works in public health ‒ and count themselves lucky to have chosen a house when they were childless that turned out to be in Lindbergh’s attendance area when they started their family. Besides their third-grader, they have a first-grader and a daughter starting kindergarten in the fall. They live two blocks away and couldn’t be happier.

“I’m involved in the parent groups, and nobody complains about teachers. It’s a win-win. (My) kids are all learning very well,” she said.

So what happened in 2013, the year that Geer Park outperformed Lindbergh by 13 points in third-grade reading? DeNeen, the Lindbergh principal, wishes she knew.

“We look at our data over and over and over again, to see if we’re missing something in the school,” DeNeen said. Students are regularly assessed on their reading levels, and shortfalls are addressed the same way they are at Geer Park, with one-on-one and small-group instruction and other remedial techniques.

“We’re ranked in the 93rd percentile for the state” overall, DeNeen said. “We’re a Reward School (awarded to the top schools, as measured by test scores, improvement or other factors). But do we have a bad year sometimes? Yes.”

Over at Geer Park, Srour is grateful for her team, her students and her parents, as well as whatever alchemy propelled them to such good results. She’s only been in her job two years, and credits her mentor and predecessor, Andrea Awada, with leaving her a school with a rich, supportive culture of learning.

Awada, now retired, likes to quote an inspirational poster she’s fond of, which she believes explains the puzzle as well as anything:

“According to the theory of aerodynamics, it may be readily demonstrated that the bumblebee is unable to fly,” Awada said. “This is because the size, weight and shape of its body, in relation to total wingspan, makes flying impossible.

“But the bumblebee, ignorant of these scientific truths, goes ahead and flies anyway.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Geer Park Elementary fifth-grade student Amen Salha proudly shows off the mustache he was awarded for academic achievement in social studies; the prize included the right to wear it in school all day. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

Geer Park Elementary fifth-grade student Amen Salha proudly shows off the mustache he was awarded for academic achievement in social studies; the prize included the right to wear it in school all day. (photo by Nancy Derringer) Kindergarten students work in small groups in Suzanne Mardini’s bilingual classroom at Geer Park Elementary in Dearborn. Small-group practice is an ideal time for English language learners to polish skills with teachers or other learning specialists. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

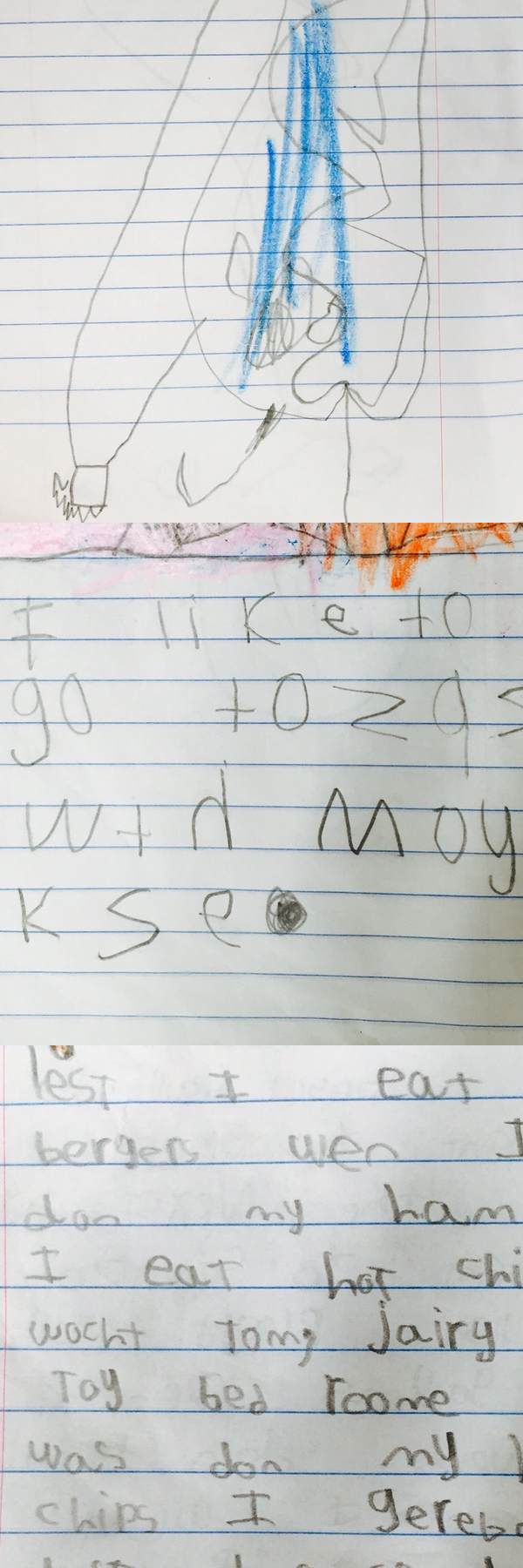

Kindergarten students work in small groups in Suzanne Mardini’s bilingual classroom at Geer Park Elementary in Dearborn. Small-group practice is an ideal time for English language learners to polish skills with teachers or other learning specialists. (photo by Nancy Derringer) Geer Park Elementary kindergarten teacher Suzanne Mardini requires students to write in journals every day, beginning on the first day of school. One student’s progress is evident as scribbling gives way to lettering and then progresses to complete sentences. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

Geer Park Elementary kindergarten teacher Suzanne Mardini requires students to write in journals every day, beginning on the first day of school. One student’s progress is evident as scribbling gives way to lettering and then progresses to complete sentences. (photo by Nancy Derringer) Jennifer Knaus reads to her fourth-grade class at Lindbergh Elementary. She stops often to ask students about facts in the story, vocabulary and other comprehension questions. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

Jennifer Knaus reads to her fourth-grade class at Lindbergh Elementary. She stops often to ask students about facts in the story, vocabulary and other comprehension questions. (photo by Nancy Derringer) Crazy Hat Day is in full flower at Lindbergh Elementary, as teacher Tracy Wright leads a discussion with her kindergarten class. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

Crazy Hat Day is in full flower at Lindbergh Elementary, as teacher Tracy Wright leads a discussion with her kindergarten class. (photo by Nancy Derringer) Lindbergh Elementary was built in 1928, the year after aviator Charles Lindbergh made his historic transatlantic flight. Lindbergh “Flyers” see references to air travel everywhere, including on this behavior chart. (photo by Nancy Derringer)

Lindbergh Elementary was built in 1928, the year after aviator Charles Lindbergh made his historic transatlantic flight. Lindbergh “Flyers” see references to air travel everywhere, including on this behavior chart. (photo by Nancy Derringer)