One teacher, 25 kids and the enormous challenge of turning around Detroit schools (Chapter 1)

Chapter One

It was all scripted.

The young social studies students at Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit would be starting the state’s tough, new M-STEP tests in April. They also faced a standardized test from the district in social studies. Not to mention a classroom test on the week’s lesson.

No biggie.

In Detroit Public Schools, a data-driven school system, on two-thirds of the days during the school year a child somewhere in the district is scheduled to take at least one standardized test.

On this particular day in April, fourth-graders filed into Room 200 chattering and laughing. They were unaware that if they earned low test scores on the M-STEP another wave of changes could be foisted on their school and staff.

William Weir, their usually unflappable teacher, stood in the middle of the classroom and breathed, inhaling a familiar feeling. The Detroit Public Schools veteran was frustrated because, like many teachers, Weir felt like he was limited in his power to help his students succeed.

If schools are the engine of a working society, too many teachers in Detroit don’t have the tools to keep the engine working properly. Weir, who teaches third- and fourth-grade social studies, looked out on his class and saw familiar challenges: The daily work of motivating students who carried problems from home along with learning gaps; the demands placed on teachers to follow scripted lessons even though, in Weir’s classroom at least, they often went over students’ heads; and larger class sizes that make it more difficult to help struggling students.

Weir would prefer a curriculum that focuses first on remediation – or “meeting kids where they are,” as he puts it – and a smaller class size so he can give each student more attention. Without those tools, sometimes the best a teacher at a place like Schulze can do is battle forward hoping lessons stick – knowing many won’t – and inspire the students to do their best.

During the test-heavy weeks of the spring, Weir sensed what the children needed first to get focused: a helping of reality.

Standing before the wiggly, fidgeting nine- and 10-year-olds, Weir told the children not to bother opening their social studies books. In his deep, echoing voice, Weir, 61, instead told a story from the days as a Detroit police officer. The one about a mom and her baby found on Christmas Day huddled near an extinguished trash can fire along Eight Mile.

They had frozen to death, homeless.

“How do homeless people go from being fourth-graders like you to that?” Weir asked the class.

The fidgeting stopped. All of the little eyeballs in the room were fixed on their teacher. One after another, hands rose into the air.

“Got kicked out,” one kid offered.

“Get drunk,” another said.

“Choose to be criminals and crackheads,” said a third.

Poor decisions and a lack of education likely led the woman to a destructive end, Weir told the class. For 45 minutes, he put off talk of test preparation and talked to the students about the importance of an education. He encouraged them to do their best.

Schools with low-income students populations are places where a teacher may be the only person a child knows who graduated from college. The classes are full of academically struggling, socially troubled and special needs students who need more intensive classroom instruction but often receive too little of it.

“If you keep giving them a curriculum with the assumption that they are not behind, they’ll never catch up,” Weir said during a quiet moment. “It’s like punishing somebody with one leg because they can’t run the race. Would you want to run that race?”

The gap between what students need to catch up and what teachers like Weir are able to provide was often in clear relief over the course of two months, when the school allowed Bridge to periodically monitor Weir’s class as the city prepares for another round of Lansing-imposed changes to its schools.

The more things change

For too many years, Detroit Public Schools and state officials who have been in control of the district have worked feverishly, and often fruitlessly, to help the district’s thousands of teachers address the ills that come with impoverished students and a deficit-laden school system.

The city’s education woes are well-documented. There is the district’s $172 million deficit, a series of state takeovers, pay cuts, worst-in-the-nation test scores, a high concentration of special needs students, teacher shortages and uncertainty about which policy change will come next.

In the meantime, teachers like Weir try to motivate students as a first step toward academic progress. Despite the challenges, Weir calls teaching “the best job I’ve ever had.”

Schulze is a relatively new building, constructed in 2002 with bond money, just a few blocks from Mumford High in northwest Detroit. The school’s 560 students have access to smart boards, a social worker, psychologist, speech therapist, instructional coaches and a full-time nurse. What they don’t have, yet, are solid test scores. Schulze ranked among the bottom 14 percent of Michigan schools in academic achievement during the 2013-14 school year.

As power brokers from Detroit to Lansing continue to debate how to improve schools in Detroit, a lot is at stake.

It’s an old story with a new twist.

Detroit exited the nation’s biggest municipal bankruptcy last year, shedding $7 billion in debt. Stories of hope – for economic recovery, population growth, job creation – are on the lips of the mayor, the governor, and business leaders.

Even so, the current generation of Detroit students in line to become the next skilled workforce in the city is falling short. Scores on the National Assessment of Educational Progress tests in math and reading have remained the worst among large cities since DPS started participating in such measurements in 2009.

To address the ongoing problems, Gov. Rick Snyder announced plans this year to re-engineer the educational power structure in Detroit, and pay off $483 million in Detroit Public Schools debt. And the legislature parked $50 million in the proposed budget that could be used for Snyder’s plan.

Whatever deal policymakers reach, it will mark at least the fourth change in how Detroit schools are run since 1999.

One teacher’s efforts

William Weir is bald and tall, with a deep voice. He has taught in DPS for 17 years after stints as a Detroit cop, a restaurant manager and a playwright in New York City. In addition to teaching social studies, Weir is also the school’s union representative with the Detroit Federation of Teachers.

He has a master’s degree in elementary education and serves on a committee that helps the Michigan Department of Education write standardized test questions and vets them for racial or class-based bias. He sports a single earring and pads his Facebook page with news about the politics of race and education. One wall of his classroom is covered in thank-you notes from students and parents.

Testing is nearly an everyday task in DPS. Even kindergarteners were scheduled to take 10 standardized tests during the school year that just ended.

At Schulze, another round of low scores could lead to change at a school that has seen plenty of that already. Schulze was among the first schools in the state identified as “persistently low-achieving” and ranked in the bottom 5 percent of Michigan’s schools in 2010, a status it has since managed to escape.

If Schulze were to backslide, its teachers and principal could be reassigned. That risk is more than theoretical. In the fall, DPS is planning to restructure staff at eight city schools that have been at the bottom of state rankings for three years or more.

In the worst scenario, school performance and restructuring could lead Schulze to lose so many students it could be closed. In Detroit, a school can be here this year, gone the next – over the past decade DPS has closed two-thirds of its schools due to low enrollment or low achievement.

How Weir’s students have performed on such tests remains unclear. DPS said it was unable to disaggregate testing data before this article was published to determine whether Weir’s students’ scores have improved. However, the school’s overall test scores have improved. For example, Schulze’s fourth-grade reading scores on the state MEAP exam jumping from 42 percent of students meeting proficency standards in 2012-13 to 54 percent reaching proficiency in 2013-14.

Weir was among teachers hired to work at Schulze Elementary in 2010 after its scores reached rock bottom. Half the staff was eventually replaced in order for the school to be eligible for federal school improvement grants.

This year, Angela Kemp was promoted from assistant principal to principal at Schulze. While she acknowledges the improving test scores, she said the desire to get better remains high.

Kemp describes Weir as a caring, grandfatherly type whose students know he loves them. He has a gift for getting students to behave, to pay attention, to try.

About half of Weir’s students read below grade level. Even so, Weir led his students to win a statewide award for a research project on the lack of neighborhood grocery stores a few years back. In the principal’s view, Weir needs to do more such projects, while continuing to help students catch up with grade-level expectations.

“Mr. Weir is old school,” Kemp said. “I need him to do more hands-on projects, tighten up his routine. Pull some kids aside. For 20 minutes teach reading so every baby can be successful in social studies and science, reading and math.”

Good teachers, she said, tailor lessons to each student’s needs and help stragglers catch up even as they challenge more advanced students in the classroom. It’s not easy, especially for teachers like Weir, who find themselves trying to teach students basic reading skills even as their class curriculum requires students to write essays.

A student “should be able to learn some social studies without knowing how to read,” Kemp insists. “We have to teach them to build something, engage that child with questions. We have to make do.”

This year the school made a change that allowed teachers in elementary grades to teach their strongest subject as opposed to teaching the same classroom of students all subjects, all day. It is too soon to know if this approach will improve student learning or be scrapped. In the past few years, the school has also tried ‒ and abandoned ‒ separating classes by gender and African-centered education.

The difference between Weir and some other veteran educators is that he will admit when his methods don’t work and try to improve, she said.

“We are asking teachers to go above and beyond,” Kemp said. “I know wherever I put him, he will try his very best.”

Nice Mr. Weir

Weir often calls the boys “Tiny Tim” (as in the sympathetic, joyful character from the Charles Dickens novel) and the girls “Tiny Tina.” Or he calls his students (and co-workers) by a name he hopes some will one day earn – Doctor.

He affirms students’ effort even if an answer is incorrect. When kids mill through the halls to change classes, several usually drop by his class to chat. If he is seated, it’s common to see a child wrap an arm around his shoulder and press their little head against his gray beard in a half-hug.

In his effort to motivate students, Weir is not above offering financial incentives. He will occasionally pay $1 for right answers to hard questions. The thank you notes covering the wall behind his desk started with a note from one girl. Now he lets students tape up a note only if they do a good job on their classwork. One reads: “To: Mr. Weir. You is so nice.”

Even nice has its limits.

Pressure cooker

Testing days like the one in April can tax even Weir’s soothing disposition.

At one point in the day, he was giving 25 third graders a Michigan history test on commerce during the Civil War. The test required them to read a line graph and circle graph and work in pairs to provide answers.

One question: “How did this invention improve Michigan’s economy? Explain by giving one example.”

The 8 and 9-year-olds struggled to read the graphs and write complete sentences. The room was quiet. Too quiet for the teacher.

“When you’re not supposed to talk, you talk. Now you can work together and you’re quiet. What’s up with that, “ Weir asked, walking around the room to look over students’ papers.

He caught two girls playing tic-tac-toe. But he missed the girl who ducked under her desk to lick hot Cheetos.

Another girl with sandy brown pigtails raised her hand. She didn’t have a question, she had an earache. Weir sent her to the nurse.

“Look at page 175, people,” Weir said, giving them a hint. “What kinds of information can you infer from the line graph?”

By the end of the 50-minute period, the children who receive special education services – about a third of the class has issues that range from attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder to learning disabilities – turned in papers with only one or two of the four questions answered in incomplete sentences.

Weir didn’t have enough time to look at every paper or answer every raised hand while students were taking the test. But a glance at the test papers told him a lot of the other kids didn’t do too much better. A handful aced it.

In many schools, a class of 25 students isn’t considered oversized. But Weir contends that it is too many considering the amount of remediation most of his students need.

“It used to be you’d have a class where five or six kids were behind. Now you have five or six who are not behind,” Weir said after class ended.

“They’re so far behind, there’s not enough time to go in depth the way you need to,” he said. “It’s not teaching sometimes. It seems like spoon feeding. That’s what makes this job so frustrating.”

Three weeks later, similar frustrations emerged in Weir’s fourth-grade class. The students couldn’t answer his questions on population in the midwest from the 1800s to 2000.

“Who can tell me how many years passed between 1850 and 2000?” he asked. No hands went up.

“There’s a dollar riding on this,” he said, holding up a greenback.

“Ten years! Fifty years! Four years,” voices yelled out.

“Look at the numbers again,” Weir said.

“A hundred fifty years,” said Ashton Moore.

“They should call you bus driver because you just took them to school,” Weir said to the boy. “Come get your dollar.”

As it turned out, it wasn’t the math or the history that tripped up the students, it was the graph. Weir used the dollar to get the kids’ attention, then turned their attention to learning to read a graph.

A boy named Quincy was summoned to the dry erase board.

“Who has a pet?” Weir asked the class.

Hands popped up, followed by yelps of “Ooh, ooh,” and “Me, me!”

Quincy followed Weir’s directions and drew a graph on the board. The class worked together to plot the number of students with different kinds of pets.

They might not remember much about Weir’s original lesson on midwestern population growth, but by switching the topic to pit bulls and fish Weir got the class interested in learning to read a line graph.

“These kids may be behind, but they are not dumb,” he said afterward. “We have to make the content relatable.”

As Weir sees it, students enter schools like Schulze well behind students in more affluent districts. The good news, he said, is that “at this age, they are still enthusiastic about school.”

On some days, though, Weir said he can see that excitement slipping away. He blames the test for some of that.

“They know they are not getting what they need,” Weir said. “How do you think that affects kids?”

Click HERE to read chapter 2

Bridge Magazine is convening partner for the Detroit Journalism Cooperative (DJC), comprised of five nonprofit media outlets focused on the city’s future after bankruptcy. The group includes Michigan Radio,WDET, Detroit Public Television and New Michigan Media. Support for the DJC comes from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Renaissance Journalism’s Michigan Reporting Initiative and the Ford Foundation.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

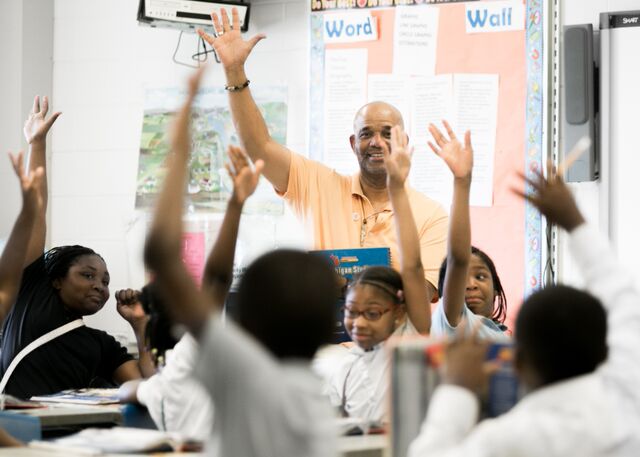

William Weir, a former cop, tries to make his lessons relatable to third- and fourth-grade social studies students at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis)

William Weir, a former cop, tries to make his lessons relatable to third- and fourth-grade social studies students at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis) Jaylen Gill, 9, answers a question in William Weir’s social studies class at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. Students say Weir’s teaching method gives them confidence. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis)

Jaylen Gill, 9, answers a question in William Weir’s social studies class at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. Students say Weir’s teaching method gives them confidence. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis) Third-grader Wisdom Smith leans in as teacher William Weir signs a form for her. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis)

Third-grader Wisdom Smith leans in as teacher William Weir signs a form for her. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis)