One teacher, 25 kids: ‘Can I sleep at night?’ (Chapter 3)

Chapter Three

One of the images that flash across William Weir’s desktop computer is a large photo of a smiling woman, presumably a teacher. It is an announcement on the Detroit Public Schools website that says the district needs more teachers.

The district has at least 75 teacher vacancies at its 101 schools, according to the Detroit Federation of Teachers. It is not unusual to see classrooms with more than 35 students.

A kindergarten class at Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts, on the city’s west side, has 37 students. Weir, who teaches third- and fourth-grade social studies at Schulze, got lucky this year with fewer than 30 kids in his classes. Next year, he won’t be so fortunate. After three teaching positions are cut at Schulze, the principal expects some classes to jump to 35 to 40 kids.

Weir allowed a Bridge reporter to sit in his classes several times over two months to chronicle how Detroit teachers go about trying to raise student achievement despite a host of challenges in Michigan’s largest public school system.

As Weir has learned, the problem with class sizes in Detroit is not only in the number of students, but the number of students with problems. Problems with reading. Problems with poverty. Problems with home lives that are not always conducive to learning.

More than 80 percent of students in DPS – and at Schulze – are economically disadvantaged. Nationally, the achievement gap between low- and high-income students is widening dramatically. In fact, recent studies show that the rich-poor gap is nearly twice the size of the black-white achievement gap.

Schulze ranked in the bottom 14 percent of all schools in academic achievement in the state in 2013-14. And that was an improvement. The school has managed to claw its way up from its past ranking among the bottom 5 percent of state schools.

Branded as a low-performing “priority school” in 2010, Schulze was forced to adopt a redesign plan, helped in part by more than $6 million in federal school improvement grant funds, state education records show. The grant paid for reading specialists, teachers’ aides, a data specialist and five instructional coaches to help remediate students and train staff. A small improvement in test scores has followed.

This year, a consultant helped with teacher training. But for the most part the extra resources went away after scores at the school inched up and the grant funding was exhausted.

A call for smaller classes

On a recent Tuesday in early June, Schulze Principal Angela Kemp hurried to the office after dealing with a kindergartener who came to school with bruises on his face. Three parents were in the office for a copy of their child’s progress report. One mother broke down in tears when she saw her child’s grades.

Kemp listened as the mother sobbed and insisted to the principal that she was trying her best to get the child to do better.

“Another teacher better not tell me parents don’t care,” Kemp said, sitting at her desk moments later. “Do they know how to handle all the baggage they have and be a parent? Maybe not.”

The challenges of the neighborhood find their way into Schulze’s classrooms, and are one reason educators at the school say they need smaller classes.

“The scale is so imbalanced when you look at what we have to deal with. Some of the stuff we know is out of our control,” Kemp said of the social and academic problems that accompany children in poverty. “But lower classroom sizes is something that should be able to happen. Many of the charter schools have it – and that’s what beats us.”

While studies are not definitive, decades of research suggests that smaller class sizes can have a positive impact on test scores and graduation rates, especially in younger grades and among disadvantaged children.

Kemp said it’s a big problem to have 35 or 40 students in one elementary school classroom, as is anticipated at Schulze in the fall because of budget cuts. But her staff is at an even greater disadvantage because a high percentage of Schulze students require more attention.

Aside from poverty, nearly one in five Detroit Public Schools students has special needs, with many of them mainstreamed into general education classes. Add to that the pressures of the new state standardized test, M-STEP, which requires more critical thinking from students and is widely expected to lower student scores, and it’s small wonder that teachers at Kemp’s school are on edge.

“I have heard of schools in the suburbs with 17 students in a class. Seventeen,” Kemp said in a whisper, as if she were sharing a secret.

“If it was just about walking through the door and teaching, everybody would be successful, but unfortunately that’s not the case. I guarantee you, get me more teachers in here and I can make it happen.”

New standards

The introduction of the new M-STEP standardized test this spring was a clear indication that students are being expected to perform at a higher level, she said.

For example, M-STEP fourth-grade math questions now require students to write sentences explaining how they solved a math problem.

That may better demonstrate how well students truly understand the problem. But it presents a greater challenge for Schulze students, many of whom are far behind their peers in reading skills.

“We have too many children who can’t read,” Kemp said. “That’s basic stuff. It keeps me up at night.”

Schools with higher income students typically have the advantage of educated parents and the advantage of lower class sizes, said Kendra Hearn, clinical assistant professor in the School of Education at the University of Michigan. Hearn taught for four years at Redford High in Detroit, then taught at the more affluent West Bloomfield High for five years before becoming an assistant superintendent for West Bloomfield School District.

She now teaches college students to become teachers.

“In suburbia – don’t get me wrong, it’s a lot of work – but there’s a little more balance and you can spend more time on the content and curriculum because you’re not having to deal with so much of the things that people assume or hope would be handled at home.”

“Think about it, if students are getting more time on task, who’s going to perform better?” she said.

She can still recall being stunned when a Detroit student wrote her a thank you letter saying he used to go to school because he knew she would be the happy person he would see that day.

“Students from college-going parents often understand that one lesson matters for their academic record, which matters in how they rank in school and how they are received by colleges. They understand the trajectory beyond the here and now,” Hearn said. “When you see all the things a teacher has to do in Detroit, that is an argument for smaller class sizes.”

Budget vs. learning

Detroit finds itself in the unenviable position of needing teachers, yet having to reduce a $172 million operating deficit that is expected to lead to budget and teacher cuts in the fall. The teacher’s union said it expects about 200 teachers will retire this summer, which could stave off projected teacher cuts next year.

Michelle Zdrodowski, a DPS spokesperson, deflected questions about class size and teacher cuts, saying that the quality of teachers is more important than the number of district teachers.

“First and foremost, our focus should be on putting the most qualified teacher at the front of every classroom and providing necessary resources to the school building level,” she said in an email. To that end, DPS recently announced administrative restructuring that includes the creation of a talent management office designed to focus on recruiting and staffing schools, she said.

Testy teacher

At Schulze, as across the state, the faculty had two months this spring to complete M-STEP tests for grades 3 to 8, and 11 in English Language Arts, math, science and social studies.

The regimen sometimes left Weir, the social studies teacher, testy and impatient, especially on those days when the M-STEP was given on the same day as social studies tests given by the district.

Weir could be found zipping around the school’s computer lab from one raised hand to another, making sure students didn’t talk or didn’t power off their computer, or try to play video games.

The students who finished quickly presented another problem. Rhonda Conyers, a fifth-grade English teacher, said she worried that some students were randomly choosing answers just to get the test finished.

But I’Lei, the fourth-grader in Weir’s class, said the M-STEP was easy.

l’Lei, who has attention-deficit issues, said he has gained confidence in Mr. Weir’s class because his teacher makes him feel smart.

Weir does more than that. He also made sure during the school year that I’Lei and his sister received a ride home from baseball practice.

Before school returns in the fall, Gov. Rick Snyder and the legislature are expected to approve changes for Detroit schools.

Regardless of whether the next round of reforms will give Weir the tools he longs for ‒ more focus on bringing struggling students up to speed and lower class sizes ‒ Weir says he will be in a classroom.

He will continue to bring attention to “meeting kids where they are” and the need for smaller classes. He will keep trying to motivate students and look for ways to make lessons relatable for them.

“I have to teach the way my heart tells me,” the teacher says. “That way I know I can sleep at night.”

Bridge Magazine is convening partner for the Detroit Journalism Cooperative (DJC), comprised of five nonprofit media outlets focused on the city’s future after bankruptcy. The group includes Michigan Radio,WDET, Detroit Public Television and New Michigan Media. Support for the DJC comes from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Renaissance Journalism’s Michigan Reporting Initiative and the Ford Foundation.

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Third-grader Toni Burgess answers a question for teacher William Weir at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. The low-income school has made small gains in recent years but, like many schools in the city, struggles to raise student learning. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis)

Third-grader Toni Burgess answers a question for teacher William Weir at the Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. The low-income school has made small gains in recent years but, like many schools in the city, struggles to raise student learning. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis) William Weir does double duty as a 61-year-old catcher between innings for the youth baseball team he coaches and as a social studies teacher at Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. The students say they know he has their back. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis) (

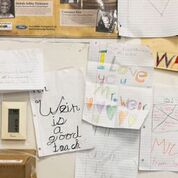

William Weir does double duty as a 61-year-old catcher between innings for the youth baseball team he coaches and as a social studies teacher at Schulze Academy for Technology and Arts in Detroit. The students say they know he has their back. (Bridge photo by Brian Widdis) ( A wall in Mr. Weir’s classroom.

A wall in Mr. Weir’s classroom.