In state with low reading scores, a West Michigan effort shows promise

One of the first things Kyle Mayer will tell you about the Reading Now Network, an intensive effort to improve reading skills among elementary students in west Michigan, is that it wasn’t formed in response to the recent third-grade reading law. That legislation will require some third graders with poor reading skills to be held back as their more capable classmates go on to fourth grade.

But the legislation, signed by Gov. Rick Snyder in October, was introduced by a lawmaker from Mayer’s west Michigan perch, where he serves as assistant superintendent in the Ottawa Area Intermediate School District. And talk of it began around the time the Reading Now Network was launched about three years ago. A coincidence, Mayer says. But a lucky one, because the network says it has helped to push education leaders to achieve some early success in boosting reading achievement among the region’s youngest gradeschoolers.

That’s good news not only for the region trying this approach, which encompasses 13 counties along Lake Michigan and inland east of Grand Rapids, but perhaps for the rest of Michigan, which has seen its performance in early reading dip in national rankings. Michigan now ranks 41st in fourth grade reading on the National Assessment of Educational Progress, or NAEP. If the state continues on its dismal path, it stands to fall to 48th by 2030, according to the Education Trust-Midwest, a nonprofit education advocacy group in Michigan.

“Poverty is not an excuse,” Mayer said of the program’s ambitions, which doubles down on the amount of time teachers in early grades spent on reading instruction. “Everyone has to be improving from where they are now.”

The clock started ticking on this year’s kindergarten class across Michigan, which under the recently approved legislation have until their third-grade year to be reading no more than one year behind grade level or face the possibility of having to repeat the grade.

‘Collaborate like never before’

The thinking behind the Reading Now Network would be familiar to any factory manager or corporate executive who ever tried to improve a process within an organization. Look at the people who are having more success, figure out what they do, and then have everyone else do it.

Mayer and his colleagues plotted data from more than 100 public school districts across the state’s Region 3, encompassing 10 intermediate school districts and 13 counties, benchmarking reading scores on the state’s former standardized test, known as the MEAP, and adjusting student performance based on poverty levels.

They identified 14 schools that consistently scored better-than-expected results year after year. Teams visited five of those 14 schools to determine what, exactly, those teachers and principals were doing differently, or better.

The educators operated under what Mayer calls a “heart-attack protocol.”

“When doctors find a better way to treat a heart attack, they don’t keep it to themselves,” he said. “No matter where you have a heart attack, no matter what hospital you go to, the best treatment is shared.”

Mayer admits the group didn’t find new ways to treat educational heart attacks. Instead, he said, the process encouraged the schools to focus more tightly on those reading strategies that worked. For the most part, the solution turned out to be fairly simple: Build everything in the early-elementary curriculum around the essential skill of reading.

“When we benchmarked the successful schools, we didn’t find anything that wasn’t already known,” he said. “We added nothing to the body of research that was new.

“The power was that (successful strategies weren’t necessarily) in another city, it was in a neighboring town. It wasn’t in Chicago, but in Zeeland. It’s not a program, it’s about the behavior of adults in schools and communities that get results.”

The group set about distilling its findings and applying them throughout the region, customizing its approach to fit individual schools. Boiled down, it amounted to a few core practices – among them, making reading an intense classroom focus, closely tracking individual students’ progress, building strong leadership in every building and refusing to give up on any student.

Although mastering reading skills has long been a core of early education, in practice it wasn’t always treated as such, Mayer said.

“When we came out of the field study and told others about the 90-120-minute reading block” – up to two hours every morning devoted solely to reading, the centerpiece of the approach – “the reaction was, ‘How are we going to do that?’” Mayer said.

Some educators worried that putting so much emphasis on reading would shortchange other subjects and special classes. The leaders’ response was simple: Make it work.

Reading now gets its own 90- to 120-minute teaching block every morning, with time devoted to large-group, small-group and one-on-one instruction, so that every student gets the attention they need. Teachers know precisely where each student is reading, according to grade level, and examine the data often. Meanwhile, best practices, in teaching and administration, are shared from school to school.

Getting schools across the region to buy in required district-level leadership to “collaborate like never before. This was 100 districts being vulnerable” and opening their doors to improvement, Mayer said. He added that not only low-achieving, high-poverty schools were targeted for improvement, but so were above-state-average schools, if their scores indicated they could be doing better given their more affluent demographics.

But he said the results have been worth it.

Mayer said when the study started, in 2012, about 9,000 students across the region were reading below grade-level proficiency. After three years of work, that number has dropped to 8,000, with the greatest gains among the poorest students. As the program evolves, he said he expects the number of underperformers to drop further and that far fewer third-graders will be required to repeat when the new law takes effect.

Constant data analysis will catch lower achievers far earlier, so that if they do have to repeat a grade it will likely be kindergarten, where repeating a year is far less traumatic for a child, Mayer said.

The third-grade reading law was prompted by a consensus among researchers that students who are not reading at grade level by third grade are far more likely to struggle academically in the future. Adding to the urgency is other research which shows that forcing students to repeat a grade presents a host of other problems for students.

While promising, the West Michigan reading data has not yet been independently reviewed outside of the region. One expert said more analysis is needed to help the state find ways to reverse its slide in early reading. That might begin with also considering reading strategies used in other, more successful states.

"While we applaud efforts to improve literacy levels, Michigan's early literacy performance continues to stagnate or even trail many other states around the country,” said Amber Arellano, executive director of Michigan-based Education Trust-Midwest, an advocacy group. “Clearly, leaders need to take a closer look at the strategies here compared to other states, especially those states producing far higher levels of achievement and improvement than Michigan.

"The data suggest it's too early to make decisions about major, statewide investments in early literacy. We still have a lot to learn -- and much to evaluate -- about what are the most effective strategies being implemented across the state, as well as outside of Michigan."

In one elementary, a singular focus

Jens Milobinski is the first to admit he “walked into a good situation” when he assumed the principal’s job at Lakeshore Elementary in Holland. Lakeshore was one of the five schools in the 2012 field study, high-scoring in spite of significant challenges.

The school, located in a rural-suburban landscape of small farms and blueberry fields, counts a little over half its student body as eligible for the free or reduced-price lunch program, the standard measure of poverty in education. About a quarter are English-language learners, many the children of the farmworkers who staff the fruit operations throughout the region. They not only speak Spanish at home, many pull their children out of school in late fall to follow jobs to Florida or Texas, returning in late winter. Some students leave the country. Milobinski said he recently worked with a teacher to put together a packet for a first-grader who was off to spend the cold months with a 30-year-old sibling in Mexico.

“It’s a huge challenge,” Milobinski said. “(The teacher) had photocopied books, reading, math. She has the brother’s email address. She’ll be in contact with him all winter.”

But Lakeshore’s building still wears the banner it raised after being named a National Blue Ribbon School in 2014, and an atmosphere of accomplishment and encouragement reigns. “Don’t forget to read 20 minutes” is the principal’s standard farewell as students leave for the day, with overnight loans of books in their backpacks. “Word walls” dominate classrooms, and a wall of lanyards covers a sizable patch in the central office.

These are worn by parent volunteers, who Milobinski and teachers recruit relentlessly to help teachers do one-on-one reading with students. The more there are, the more children can get focused attention. The library is spacious and bright, roomy enough to accommodate several racks and tables for a Scholastic Book Fair, which is also promoted with signs inside the school and out.

But well inside the central office is where the work is measured. The percentages of students at each grade level who are reading proficiently, below, or well below grade level are recorded on a whiteboard. The numbers are updated every seven weeks, when the whole staff (administrators and teachers alike) meets and plots strategy, setting goals for the next seven weeks..

Milobinski credits his teaching staff with extraordinary dedication.

He recalled that the parents of one student said they wouldn’t be reading to their child over the holiday break, so the teacher asked if she could call daily during the break and read with the child over the phone. The parents said they wouldn’t mind, and the teacher followed through, calling every day and reading with the student, trading paragraphs back and forth for 45 minutes at a time.

Data and more data

The importance of meticulously measuring each student’s progress is essential.

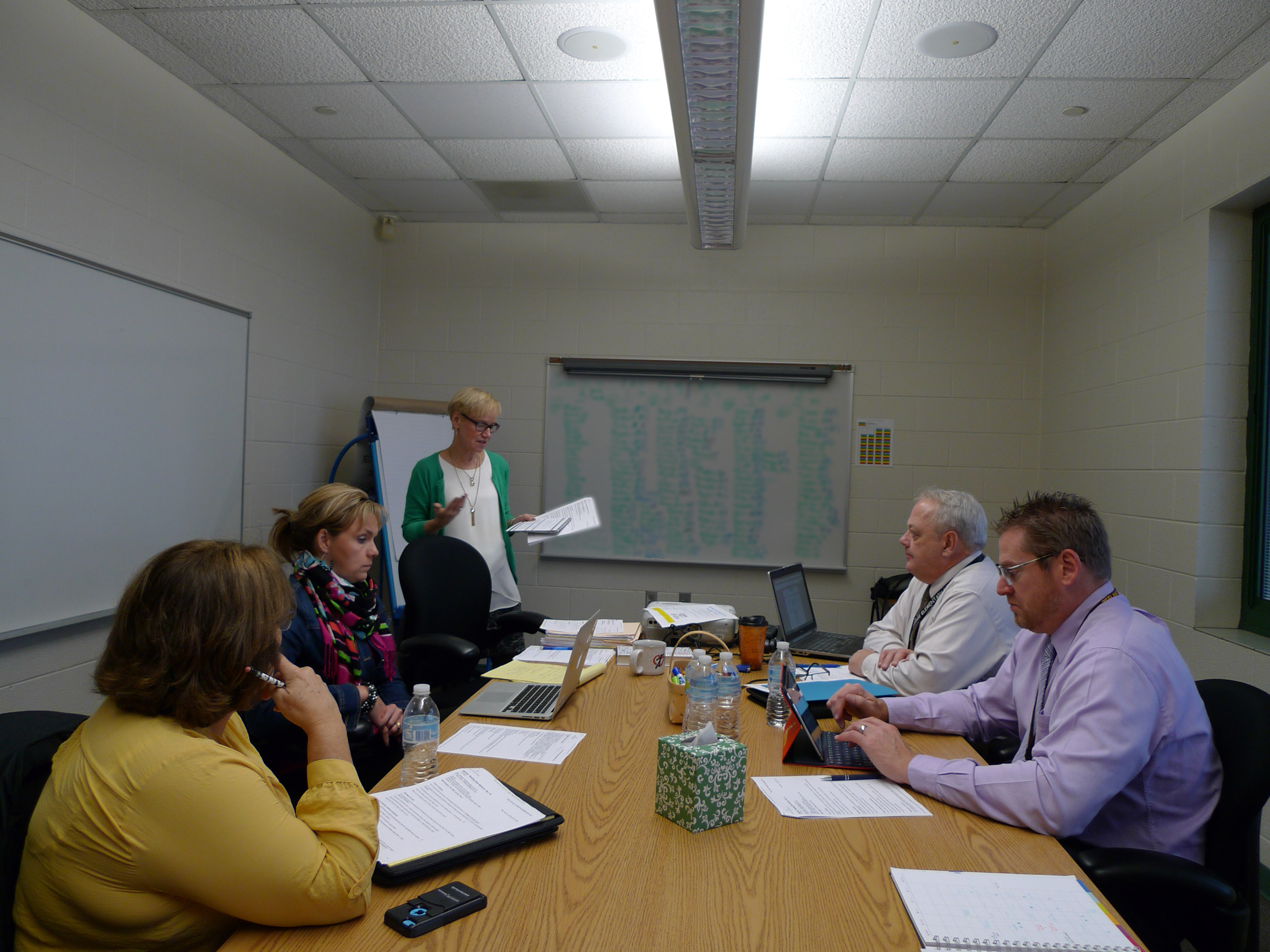

At Woodbridge Elementary in Zeeland, an above-average school that was determined to be falling short of its potential, the conference-room whiteboard has been given over to listing every student in the school who is reading below grade level (out of sight of these, or any other student). As students advance, each letter is crossed out and the new one written in.

Barb Johnson, who was principal at one of the five higher-achieving schools, led an in-service training for Woodbridge principal Michael Dalman and other principals recently, suggesting strategies for using the 90-to-120-minute reading block each school now has.

The goal, Dalman said, is for no third-graders to be retained in three years. Forcing a child to repeat third grade is demoralizing and humiliating for an 8-year-old, and may end up being even more of a setback.

“There’s no magic pill. Retention isn’t going to solve the problem,” Dalman said. “What we’re doing here will solve the problem.”

This approach -- bringing even building leaders into the team for individual students, via data analysis -- is key to the program’s success, Mayer said.

“We all know how to be professional educators. We can track every kid until they are proficient. Why weren’t we all not doing that before?” Mayer asked. Individual data analysis is still fairly new in education and not universally adopted, he said, answering his own question.

He said skeptics sometimes ask whether, with the intense focus on reading, other subject areas like science or math are neglected. Not by test scores, he replies, which he said have not slipped as a result. But the success of the Reading Now Network, he said, suggests the next step:

“Math Now Network.”

Michigan Education Watch

Michigan Education Watch is made possible by generous financial support from:

Subscribe to Michigan Education Watch

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Jens Milobinski, principal at Lakeshore Elementary, stands in front of the dozens of lanyards worn by the parent volunteers he recruits to read one-on-one with students during the school day. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Jens Milobinski, principal at Lakeshore Elementary, stands in front of the dozens of lanyards worn by the parent volunteers he recruits to read one-on-one with students during the school day. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) Ottawa Area ISD Assistant Superintendent Kyle Mayer worked on the leadership team that developed the Reading Now Network.

Ottawa Area ISD Assistant Superintendent Kyle Mayer worked on the leadership team that developed the Reading Now Network. Lakeshore Elementary parent Ashley Travis shops at the school’s book fair, along with her daughter Evelyn. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Lakeshore Elementary parent Ashley Travis shops at the school’s book fair, along with her daughter Evelyn. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) Brown Elementary Principal Barb Johnson, standing at left, leads a training at Woodbridge Elementary, with that school’s principal, Michael Dalman, in white shirt, and other staff. The names of every student who needs to improve to grade level is written on the whiteboard behind them. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Brown Elementary Principal Barb Johnson, standing at left, leads a training at Woodbridge Elementary, with that school’s principal, Michael Dalman, in white shirt, and other staff. The names of every student who needs to improve to grade level is written on the whiteboard behind them. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)