A Chaldean enclave in Detroit yearns for Syrian refugees

Nida Samona and her family were among many Chaldean immigrants from Iraq who settled in the densely-populated and tree-shaded Detroit neighborhood east of 7 Mile and Woodward in the 1970s. That’s when men like Nida’s father spent their days playing backgammon and cards in coffee shops along 7 Mile, which was lined with Chaldean-owned stores.

Today, the neighborhood, now called NorthTown, is a mixture of solid old houses, rotting bungalows and 72 new modular homes mixed with acres of weedy empty lots.

Most Chaldean residents are gone, just like the coffee shops, though Chaldeans still operate several businesses, including a restaurant, collision shop, wholesale fish market and bakery. It’s in this community that activists hope to revive a Middle-Eastern neighborhood, with an eye toward filling scores of newly built homes with refugees now pouring out of Syria.

But this dream of community revival will first have to change some minds at city hall. While the Arab-American and Chaldean Council, which has invested heavily here, is lobbying for city permission to build a large housing project, the administration of Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan appears to favor less ambitious plans. Complicating matters, it’s unclear if newly arrived Syrians would choose this 7 Mile neighborhood when there are so many others in metro Detroit with more substantial Middle-Eastern populations.

Loyal to neighborhood

Where a casual passerby might see a downward-spiraling neighborhood, Samona and her colleagues at the council see a district filled with promise. The council has spent $14 million on its five-building social-services campus along 7 Mile.

They say the community can revive if the new housing north of 7 Mile can be greatly expanded and if the houses are filled with the Syrian refugees Detroit has said it is open to accepting. The council envisions a restored ethnic neighborhood with the vibrancy of Mexicantown.

“This neighborhood has walkability,” said Samona, the council’s senior vice president of operations. “Services are right next door; you walk right up to it. You have people speaking your language, plus church, school, physicians. More businesses will open if that mass of people comes in.”

Haifa Fakhouri, the council’s president and CEO, noted the organization stayed in the neighborhood even after the Chaldean neighbors departed. The group has continued to serve mainly African-American residents in the area while it worked with the developer of the new homes north of 7 Mile and made improvements to the streetscape.

“Now, we want to house refugees from Syria,” she said. “We’re thinking about up to 5,000 families.”

But in the Duggan administration, city planning chief Maurice Cox and Arthur Jemison, director of housing and revitalization, do not appear to share the council’s enthusiasm for building hundreds or even thousands of housing units north of 7 Mile.

Speaking to Bridge through Duggan spokesman Dan Austin, Cox said he urged the council to follow a more modest strategy, focusing on “select demolition of abandoned homes” along with rehabbing existing housing stock, mostly in the area south of 7 Mile.

Cox said the city has also suggested the council “explore a landscape strategy for the stewardship of many of the vacant lots in the neighborhood...until property values increase and development can be spurred.”

One thing both sides agree on is bolstering 7 Mile, between Woodward and John R. Today, the street has the snaggletooth look of many Detroit thoroughfares, with functioning establishments sprinkled among boarded-up stores, vacant lots and raggedy weeds. City city officials want housing along the street, part of a larger emphasis on increasing population density in certain parts of Detroit. Cox suggested using “7 Mile as a potential mixed-use residential corridor and choose select sites for new multi-family construction.”

As for filling the neighborhood with Syrian refugees, Austin, the mayor’s spokesman, said the city can’t steer people to any one location. Already, NorthTown will have to compete with neighborhoods with more substantial Arab-American populations in Oakland and Macomb counties, not to mention Dearborn and the Warrendale area of Detroit that is adjacent to Dearborn.

But Samona is undeterred. “We’re going to try to come up with some creative solutions,” she said.

Syrians and refugees

The arrival of refugees from the chaos in the Middle East, most notably Iraq and Syria, has become a divisive political issue in some regions of the country, but Arab and Chaldean (Iraqi Christians) communities are long established in Michigan, especially in metro Detroit.

The idea of accepting newcomers enjoys bipartisan support. Officials from Republican Gov. Rick Snyder to Duggan, Detroit’s Democratic mayor, have expressed a desire to welcome refugees, citing economic as well as humanitarian reasons

Duggan traveled to Washington Oct. 8 for two days of meetings with Obama administration officials, including Samantha Power, U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations. Part of his agenda involved the city receiving some Syrian refugees.

“I expect Detroit to play a role, like other cities do,” Duggan told reporters recently. “I told the president that Detroit will step up, like other cities should.”

The state accepts an average of 4,500 refugees each year, according to the governor’s office. Through June, 2,028 refugees settled in the state this year – about half from Iraq. About 50 came from Syria.

“To talk about numbers at this point is premature, but we can say that we are certainly open to the idea because we are a welcoming state,” said Dave Murray, Snyder’s deputy press secretary.

President Obama, pressured to show the United States is doing its part to resettle refugees, has committed to accepting at least 10,000 displaced Syrians over the next year of the 85,000 refugees the U.S. will accept in 2016, the White House has said. The ceiling of refugees from all countries will increase to 100,000 in 2017.

Rasha Basha, who works with metro Detroit agencies to resettle Syrian refugees, said most Syrians in southeast Michigan live in Oakland County, so some Syrian refugee families have been settled in Pontiac, the county seat.

In addition to proximity to fellow Syrians, security is chief consideration in finding places for refugees to live. “These families have been through a lot,” Basha said. “They escaped war and bombs falling, and they have fear, and they’re dealing with emotional stress. A big part of finding homes is the safety, too.”

A welcoming neighborhood

Potential refuges would find plenty of help at 7 Mile and John R, though only a relative few neighbors of Middle-Eastern descent remain.

Starting in 1998, the Arab-American and Chaldean Council has built or converted five buildings in the area – two of which posses a Middle Eastern architectural flair – offering a full range of social services, including behavioral health; state welfare programs; substance abuse and senior citizens programs; dental facilities; a full-size basketball court, computer lab and a Detroit Community Health outlet.

But as the council was staking its future along 7 Mile, Chaldeans were moving to the suburbs, leaving the neighborhood as a mix of some of Detroit’s most haunted streets, including W. Robinwood, which at its worst, in 2009, had 60 abandoned homes – out of 66 total houses – between Woodward and Charleston. Samona estimates 15 to 20 percent of neighborhood residents are Chaldean.

“The whole neighborhood has dwindled, regrettably,” Samona said.

The council also has worked to spruce up the look of the area by improving storefront facades, building a small park and working with the developer who has built $15 million of low-income housing north of 7 Mile called Penrose Village.

The developer, Sam Thomas, has constructed 72 units of low-income housing in two phases, using funding generated by tax credits. Most are single-family homes; some are duplexes.

One striking part of the development is a farming section that Penrose Village has undertaken with the GrowTown nonprofit that supports urban agriculture. In addition to cropland, the GrowTown area contains a house dedicated to art projects and a 4,000-square foot home with living units and meeting space. Next door, workers are building a covered community gathering area, modeled after a Greek agora, complete with Mediterranean-style white columns.

The council has ambitions for Thomas to expand from the 72 houses he has already completed to up to 5,000 units, said Fakhouri, the council president. But Thomas is cautious. He said he is waiting to make sure the first two phases continue to work well and to understand market demand.

“I’d love to build housing right on 7 Mile, convert some of those buildings to housing, with some commercial” space, he said.

Old businesses and new

The 7 Mile-Woodward neighborhood has its advantages: It is centrally located amid sprawling metro Detroit. It’s a mile south of the Oakland County border, about a 15 minute drive from downtown and less than a mile from new developments on the site of the old state fairgrounds. Across Woodward to the west are the mansions of Detroit’s historic Palmer Woods district and some of Detroit’s most desirable neighborhoods.

“It might look a little tired on a few streets,” the council’s Fred Batayeh said, “but there is a lot going on underneath the surface that is just starting to bubble through.”

That might seem like an overly cheerful view for an area that contains some of the most blighted blocks in a city with an international reputation for blight.

But along 7 Mile Road, at B & S Collision, Pete Kassab echoes Batayeh’s optimism. He has been repairing cars at the site since 1979, and sees new lighting, graffiti removal and cleaner streets as signs of renewal.

“I think it’s on the rise,” he said. “We’re doing well. I have no intention of moving out. We need new housing, though. That would help a lot.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

New housing on Carman Street is giving hope to local civic leaders that Syrian refugees and others will move into Detroit’s NorthTown community. (Photo by Merinda Valley).

New housing on Carman Street is giving hope to local civic leaders that Syrian refugees and others will move into Detroit’s NorthTown community. (Photo by Merinda Valley). Fred Batayeh and Nida Samona of the Arab-American and Chaldean Council are pushing to rebuild the former heavily Chaldean neighborhood. (Photo by Bill McGraw)

Fred Batayeh and Nida Samona of the Arab-American and Chaldean Council are pushing to rebuild the former heavily Chaldean neighborhood. (Photo by Bill McGraw) Old homes along Derby Street. (Photo by Merinda Valley)

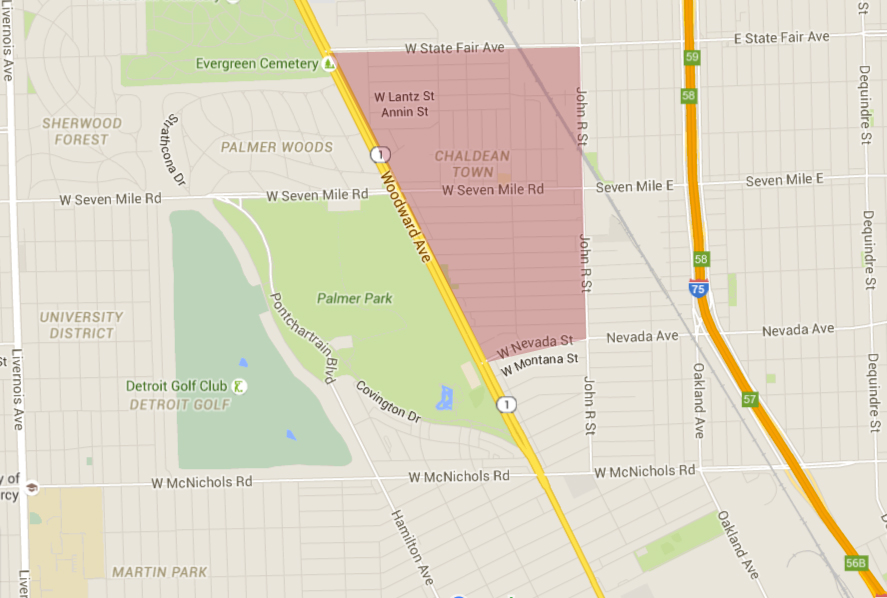

Old homes along Derby Street. (Photo by Merinda Valley) Detroit’s NorthTown neighborhood: The Arab-American and Chaldean Council wants to fill this fraying neighborhood along 7 Mile in Detroit with an expected flood of Syrian refugees

Detroit’s NorthTown neighborhood: The Arab-American and Chaldean Council wants to fill this fraying neighborhood along 7 Mile in Detroit with an expected flood of Syrian refugees An empty section of the NorthTown neighborhood, at Havana and Penrose. (Photo by Bill McGraw)

An empty section of the NorthTown neighborhood, at Havana and Penrose. (Photo by Bill McGraw)