Detroit struggling to create jobs outside of downtown

Detroit has a host of well-documented problems – poverty, crime, street lights, mass transit – that hamper its recovery.

But the ability to create jobs may be its biggest hurdle. More jobs could mean less poverty and more tax revenues to fix the many broken things.

“It’s absolutely critical that Detroit grow jobs,” said Teresa Lynch, nonresident senior fellow at Brookings Institution and a principal at Mass Economics, which is helping the Detroit Future City’s group work on economic development strategies.

A large part of the problem is where jobs are located in the city. A Bridge look at jobs within Detroit’s sprawling boundaries shows that perhaps no other large city in the country finds most of its jobs confined to such a tiny sliver of its land, with much of the rest a veritable jobs desert.

Hundreds of thousands of city residents, many without access to a car, live in areas where there are fewer than 200 jobs for every 1,000 residents, neighborhoods that are miles away from where most jobs can be found, both in and outside of the city. Nearly 80 percent of city residents live over 10 miles from a central business district, one of the highest rates of the country.

“It’s a huge challenge for the city,” said Paul Hillegonds, chairman of the Regional Transit Authority, which was created by the state legislature “to plan and coordinate” transportation services in Wayne, Oakland, Macomb and Washtenaw counties.

As Mayor Mike Duggan and other civic leaders work to take advantage of the city's Midtown-Downtown economic corridor, it's also looking to bolster employment in the neighborhoods, where jobs are difficult to find.

Detroit has one of the worst jobs per capita rates among big cities, due largely to the closing of large manufacturing plants that were once spread across the city.

Roughly half of the city’s population lives west of Woodward Avenue - more than 335,000 people. But across that vast stretch of Detroit there are only 30,500 jobs – less than one job for every 10 people. Similarly jobs-poor areas abound on the city’s east side.

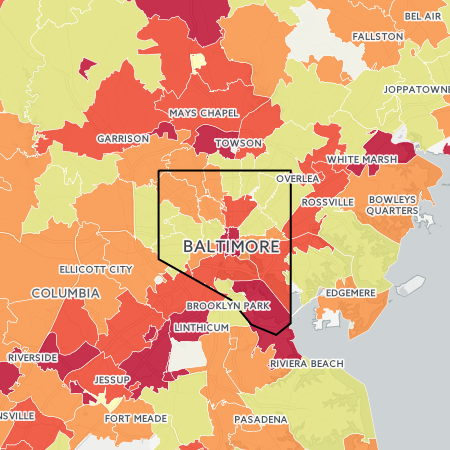

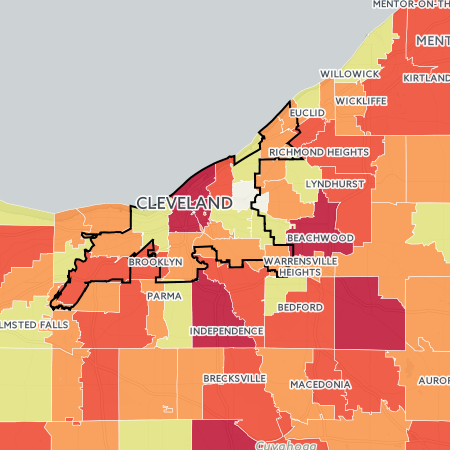

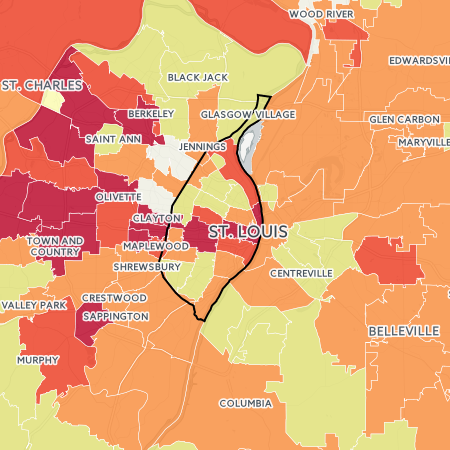

That compares to the 64,000 jobs from Midtown to downtown, where just about 18,000 people live (Detroiters hold about 27 percent of the Midtown-downtown jobs). All told, the city has a little over 200 jobs for every 1,000 people, well below St. Louis’s 613, Cleveland’s 481, Grand Rapids 477, Milwaukee’s 450 and Baltimore’s 391.

One of the nation’s largest cities geographically, Detroit is struggling to improve its city bus system while a number of the most jobs-rich suburbs do not participate in the regional transit system, with the spread-out nature of the region complicating the jobs problem for Detroiters.

The Duggan administration said it is addressing the issue several ways: One, by improving the bus system so people living far from active commercial centers can more easily get to the jobs. But the city has also sought to work directly on developing jobs, both within the already-successful Midtown-Downtown corridor and in the neighborhoods themselves.

It announced the creation of an “innovation district” centered on the corridor that will look to take advantage of the assets already in place – the hospitals, universities and businesses – to attract more businesses.

That area, bounded roughly by Henry Ford Hospital to the north, the Detroit River to the south, I-75 on the east and the Lodge Freeway on the west, – comprises just 3 percent of the city’s land mass – yet is home to 55 percent of its jobs. Yet nearly three-quarters of those job are held by non-Detroiters. The area is home to Wayne State and two hospital systems as well as the growing core of businesses owned by Quicken Loans.

A group of 17 leaders in private business and the education community have been appointed to a committee to outline plans for the district. It’s first report is due out soon. But the city is going to take a “hands-off” approach to it, Duggan said last year.

He named Henry Ford Health Systems CEO Nancy Schlichting as chair of an advisory committee tasked with developing a formal plan to make Greater Downtown Detroit an innovation district, and expanding its reach to other parts of the city.

There will be no tax breaks available for in-district businesses beyond what the city already offers. There may be tweaks to the city’s zoning rules to allow for more mixed-use development, Jed Howbert, executive director of Duggan’s jobs and economy team, said in an interview. The zoning changes would allow for more mixed-use commercial and residential developments that are a hallmark of new urbanism.

What the city is doing, he said, is helping connect businesses within the district with city residents seeking jobs.It has become a training program to help residents develop the lower-level tech skills that some of the new employers need.

The city is also working with the New Economy Initiative of Detroit, funded with $100 million in foundation money to offer grants and expertise to entrepreneurs and others to encourage city businesses to buy supplies from city-based businesses, said Pam Lewis, a senior program officer with NEI. In 2012, local businesses bought over $500 million in supplies from city businesses; it’s expected to top $900 million this year, she said.

Other city and private programs are underway: using $3 million in federal block grant money to get entrepreneurs started in neighborhood businesses and looking to encourage development of “critical commercial corridors” around the city, Howbert said. The program, called Motor City Match, is offering $500,000 in grants each quarter to start new businesses and to help landlords get buildings ready for active use. Comerica Bank is also bankrolling entrepreneurs, he said.

Though the city would surely love one or five 2,000-job manufacturers to show up, those are rare in today’s economic climate. “There are very few of those investments getting made,” said Lynch of Mass Economics.

Smaller manufacturers are still choosing the city and the region, but not in numbers that match the days of the Big 3’s heyday.

“Most jobs are created by small and medium size businesses,” Howbert said.

That wasn’t always Detroit’s story. For decades, many of the city’s neighborhoods teemed with nearby jobs as housing sprung up around the dozens of manufacturing plants in the city. But the plants moved or closed altogether. The neighborhoods remained but many have fell into disrepair as unemployment soared and residents moved out toward the jobs that once were plentiful in the city.

“If people can’t get to jobs closer to where they live, they soon consider moving closer to the jobs. That’s the story of Detroit,” Hillegonds said.

And solving the problem, either with better transit or more home-grown jobs, will write the next chapter.

Bridge Magazine is convening partner for the Detroit Journalism Cooperative (DJC), comprised of five nonprofit media outlets focused on the city’s future after bankruptcy. The group includes Michigan Radio,WDET, Detroit Public Television and New Michigan Media. Support for the DJC comes from the John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Renaissance Journalism’s Michigan Reporting Initiative and the Ford Foundation.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

A stretch of Livernois Avenue, tabbed as the "Avenue of Fashion," is a "critical commercial corridor" where city leaders now say job growth can once again take place.

A stretch of Livernois Avenue, tabbed as the "Avenue of Fashion," is a "critical commercial corridor" where city leaders now say job growth can once again take place.