In a gentrifying Detroit, an uneasy migration of urban millennials

Detroiters like to toss numbers around, not necessarily as data, but more as signifiers. There’s “the 313,” the city distinguished from its suburban area codes. You used to be able to buy a T-shirt reading 713,777, Detroit’s population in the 2010 census. To this, add another:

That’s shorthand for the 7.2 square miles of greater downtown Detroit, and encompasses freshly scrubbed neighborhoods in downtown, Corktown, Midtown, New Center, Woodbridge, Eastern Market, Lafayette Park and Rivertown. These are also the neighborhoods where rents are rising, new apartments are being built or renovated faster than you can say “subway tile backsplash,” and affluent muppies are outbidding their less-affluent peers for loft-style living space with river and skyline views.

Just a few years ago, many of these buildings were like thousands of others in the city – unused, shuttered, short of blighted but with blight perhaps on the horizon. Today, they’re home to the vanguard of the most-publicized urban migration in years, that of the young, moneyed and well-educated back into Detroit. At least, into these 7.2 square miles.

And tucked into those moving boxes, like Pandora’s mythical one, are either the evils of gentrification or its benefits. It all depends on your attitude.

Or, for that matter, your terms. Gentrification doesn’t have a hard-and-fast definition, but in general it describes the phenomenon of an urban neighborhood rising in desirability, attracting more affluent residents. Poorer, longtime residents may find themselves pushed out by such economic factors as rising taxes and rents, or wake up one day to find familiar storefronts transformed into an unwelcome warren of tapas bars and single-origin fair-trade coffee shops.

(For the uninitiated, Bridge created an interactive map of renos and hangouts that have sprung to life in recent years to house, feed and entertain newly urban residents.)

In Detroit, most casual observers would wonder what the problem is. The city has suffered for years from population loss and its related miseries, so any reversal, however small, can’t be bad, right?

That depends on whether you arrived two or 20 years ago, whether you’re one of “the blank-slate people” (those who move to Detroit and marvel over its possibilities with that expression, as though hundreds of thousands don’t already live there), or those who use charged terms like “colonization” (as if a young couple rejecting Oakland County is akin to plundering Africa’s gold trade). And yes, the racial subtext is real.

Atomized in Capitol Park

Lauren Hood is 42, African American and grew up middle class in Detroit but was educated at Detroit Country Day in Bloomfield Hills, and later at University of Detroit-Mercy. Today she works for Loveland Technologies, which performs mapping and data analysis on, and in, Detroit. Her background prepared her to move like a local through the various ecosystems that tend to crash into one another in the city – housing activists, nonprofit groups with improvement agendas, young immigrants, older long-termers, corporate interests and more. In this small town within a big city, she sometimes finds an “echo chamber, where I’m the only one of me — black, Detroiter.”

And as “a citizen of two nations,” she finds herself conflicted.

“Yes, we want new things to come, we want more resources for the city, but we want it for everybody,” Hood said. And to citizens of one nation, the other nation has rigged the game. Take the rent subsidies paid by some companies for employees who choose to live downtown or in Midtown. “Where’s the subsidy for the people who have been here all along and toughed it out?” she said. “Why can’t they get something?”

Which brings the discussion to 1214 Griswold Street, a block where the changes sweeping through the 7.2 can be seen in one compact space. The conversion of the rent-subsidized Griswold Apartments overlooking downtown’s Capitol Park, once home to more than 100 low-income senior citizens, into market-rate apartments is the example of gentrification that comes up in conversations again and again.

Rechristened “The Albert,” after its architect, Albert Kahn, the new building was announced with a self-satisfied video from its developers, featuring young people proclaiming, “Detroit is my generation’s city.” As shots of the city’s attractions fly by, an unidentified voice enthuses over the “chevron-patterned, dark-wood flooring” and the kitchen’s “custom-made roll-away island,” while another says “there’s a reason everybody’s down here.”

Advocates for the building’s displaced poor, mostly African-American seniors howled in protest. The Curbed Detroit blog called the promo “unbearable.” The video was later trimmed of its most tone-deaf remarks, but the damage was done. Well, not all the damage: one guerilla videographer took the original promo and added heartbreaking interviews with the elderly tenants facing eviction. (A spokeswoman for developer Broder & Sachse declined to comment.)

Even though the original residents received relocation assistance through the Neighborhood Service Organization and were placed in other housing, Hood, for one, sees the event as a tragedy. “Moving is traumatic at any age, but having to leave as a senior citizen?” she said. “And what about the community they built there?” It was, in one fell swoop of capitalism, atomized, for people willing to pay over $2 per square foot of chic living space.

Change is inevitable

But what is the alternative? It’s the nature of every city to change, and most of Detroit’s change hasn’t been for the better. Are the residents of the old Griswold Apartments simply collateral damage?

“People want the community to improve, but the improvement will come with investment, and investment comes when people feel they can get a return,” said Austin Black II, a Realtor whose territory is Midtown and other parts of the 7.2. “That means buying buildings and charging rents to cover costs. The spinoff is more investment.”

At the moment, Black is showing off the sort of rehabbed loft space that makes urban-living aspirants drool. Located in the Willy’s Overland building just off Cass, its south-facing windows overlook the city’s skyline and 2,000 square feet flow in and out of an open floor plan. Closing was still a few days away, but it was pledged to a couple from Utah, who were moving their lives closer to their college-student daughter. The price was in the $400,000 range, and they were happy to pay it, Black said; after all, the same place in Chicago would be well over $1 million.

Even at these prices (most are lower), units were going quickly, Black said. Resale properties are sitting on the market for eight to 10 days. Asking-price deals are common. For an agent who survived the recession, happy days.

To Black, the calculus may make some uncomfortable, but facts are facts:

“In order for the city to thrive, it has to be a balance of incomes. We all agree these historic neighborhoods are beautiful and should be preserved, but the cost to maintain them is very expensive. So you have people who live here and can’t afford the upkeep, and the result is, the neighborhood will deteriorate. These houses were built for people with high incomes. It can cost $6,000 to rebuild a chimney.”

The market may be a cruel mistress, but it cannot be denied.

Jon Zemke is a freelance journalist and small-scale real-estate developer, buying, rehabbing and renting houses and small apartment buildings, mostly in the central city. To him, what’s happening is simply a correction to the ludicrously low rents of yesterday.

“I don’t think people are being uprooted from this city. Just because their downtown loft is starting to approach fair-market value when they were getting an amazing deal before doesn’t make it wrong,” he said. “If I see one more young white person on my Facebook complaining about gentrification, I will reach through the computer and smack them.”

Sleek loft conversions aren’t the only places to live, Zemke says, noting that being priced out of one area should be good for other neighborhoods, as the less-affluent push into less-trendy sections of the city.

Affordable options remain

Sue Mosey, president of Midtown Detroit Inc., a planning and development nonprofit, has worked on boosting Midtown since it was called the Cass Corridor and known for its squalor and prostitutes. She rejects the very idea that gentrification is going on, at least in Midtown, where her organization is acutely aware that diversity – of age, income, occupation and ethnicity – is both the neighborhood’s strength and selling point.

“There is affordable housing everywhere in Midtown,” she said. “Is the market-rate (housing) going up? Yes. But that’s going to happen.”

At the same time, “there has been a lot of substandard housing that isn’t safe, that people shouldn’t be living in, which has led to owners milking properties and not making improvements.” As the market improves, they will be prompted to invest or sell, she said.

“It’s a very complicated issue,” Mosey said. “We all want affordable, safe, nice and business. But you have to have an economic base to make a neighborhood work. You have to have a mix.”

Define your terms

Part of the confusion surrounding the topic in Detroit lies in its paradox: Don’t we want Detroit to get better, richer, more prosperous? Don’t we want people to be drawn back to the city, after decades of flight? If so, where are they supposed to live? No one has a clear answer. The city is full of empty and available housing, but much of it is undesirable because of its poor condition or location. The 7.2 square miles of the central city is, for better or worse, alive.

A 2013 research report by a Federal Reserve Bank economist defines a gentrifying neighborhood as one that goes from the bottom half of the distribution of home prices in the metropolitan area to the top half in a set time period. No less than 94 percent of Detroit’s housing lies in the bottom half, and only 3 percent actually gentrified in the 2000-2007 time period, the report said. Even before the housing crash, there was still enough affordable housing for anyone who wanted it.

And that was before the foreclosure crisis pushed longtime Detroit residents out of homes all over the city. It’s that raw wound – residents being evicted from housing that no one wanted to buy, at the same time newly urban professionals scooped up newly renovated properties – that rankles many.

Zoe Villegas, 26, is a student and housing activist who feels this acutely.

“Of course it’s good for a neighborhood to experience progress,” she said. “But we need a dialogue between people who are moving in, and people who’ve been there. ...The last couple of years, there have been some glaring contradictions. It manifests with social media, and with larger forums like Metro Times, illuminating homes that are available after foreclosure. I see a lot of people celebrating these foreclosures, without taking into account that people lived in these houses before.”

To Villegas, excitement over an improving Detroit would be easier to swallow if it were accompanied by concern over the residents who struggle to keep their homes. Some cities are taking steps to prevent displacement of longtime residents in gentrifying areas by, for instance, putting caps on property taxes, an issue that Mayor Mike Duggan vowed to also address.

“There’s a solution where people don’t have to be displaced,” Villegas said. “We can protect people from foreclosure to give them resources they need.”

Respect history

Change of any sort is upsetting, and easing the upset is something those behind downtown development should be thinking about, said Meagan Elliott, a planning consultant who has done work for the city and graduate student who has studied gentrification in Detroit and elsewhere.

“By most standard constructs, it’s not happening in the same way” as in other cities, Elliott said. She cites Chicago and Washington D.C. as places where neighborhoods were transformed, seemingly overnight. But in Detroit, the process is a trickle, not a flood: “(Gentrification) wouldn’t even constitute a drop in the bucket in terms of the stabilizing effects of the population loss. That’s why I’m so interested in how it happens in Detroit.” Because Detroit is evolving far more slowly, she said, there’s a chance to spot – and potentially correct – exclusionary practices before they happen.

Viewed most negatively, Elliott prefers the term “cultural displacement” to gentrification, believing it more accurately captures the phenomenon of what, exactly, happens when a neighborhood improves to the detriment of its long-term residents. She cites the way, for example, a new coffee shop might be remodeled to take advantage of architectural details like exposed brick and reclaimed wood, a look that telegraphs “expensive” to long-term residents who may not be familiar with a pourover and wonder why customers are staring at computers all day. To those residents, the arrival of such a business can be as bewildering as a party store with bulletproof glass plopped in a neighborhood in Bloomfield Hills. It’s subtle hostility in mercantile form.

“A lot of the people I talk with, at some point we talk about tensions being calcified over time” in certain neighborhoods, Elliott said. “When I ask them what can (new residents) do to soften them, one person said, ‘Have them take a test, like immigrants do.’ While that would never happen, it does speak to the need for newcomers to understand the city’s history, the neighborhood’s history, when they become a part of it.

“To come in without that context or understanding is one of the most damaging things that happens over and over again.”

Which is exactly what Joel Peterson is seeking to avoid with Trinosophes, his Gratiot Avenue cafe/performance space that opened last year. At first glance, it looks like the sort of new-Detroit cool spot that is pushing out the old, but Peterson said it’s anything but.

“We don’t want to identify as ‘new Detroit.’ We are old Detroit. (Trinosophes is) based on actual relationships, actually being part of the community. We’re not trying to think of how to bring in this or that demographic. We’re inclusive in everything we do.”

Peterson has lived in the city for 22 years, having moved in at age 20 after growing up in Grosse Pointe. He lived 12 years on the block that Trinosophes occupies in Eastern Market. Having paid his dues, he sees the neighborhood as a living thing, with a wide range of current and potential customers. So Trinosophes employs such practices as “caffé sospeso,” the Italian tradition of paying double for a cup of coffee or other drink, with the credit applied to a later, less-fortunate customer.

“In the recent past, relocating to Detroit carried with it a standard of behavior and a gradual and unheralded integration in the community. That’s what’s missing now,” he said. “I don’t see people taking the steps to truly embracing the community that’s always been here.”

Moving on

“Where’s the subsidy for the people who have been here all along and toughed it out? Why can’t they get something?” – Detroit resident Lauren Hood, referencing the rent subsidies some companies offer employees to move downtown.

In the end, as the gentry move into a suddenly cool area, the cool people who blazed the trail may find new places to transform. Consider the path of Gabby Buckay, an artist who for 16 years lived in a sixth-floor walk-up loft in a graffiti-splashed building across Capitol Park from the Griswold Apartments-turned-Albert.

Her apartment, and her rent, were the stuff of legend – 2,500 square feet for $550 a month. Admittedly, it was a dump, so bad that Dan Gilbert, who bought the building last year, didn’t even have to evict the tenants – the fire marshal took care of it after an initial inspection.

“You could do anything there,” Buckay said. “You could have any kind of pet, do anything you wanted to do. There was this handyman who would smoke pot with people. It was very lax.”

Arriving in 1999, at just 20, she had a colorful, salad-days parade of neighbors – “regular guys, then junkies, then a guy who shot guns out the window, a Goth couple, lots of weirdos.”

In the past few years, it began to fill with other artists. When the fire marshal’s order came to vacate by the end of February, a cry went up on alternative media, but the deed was done. Buckay, for her part, was ready to get out.

“Living downtown was such a weird, bizarre experience. As it evolved, I liked it less. Tigers games would create traffic. I started having to pay $85 a month to park. It got exhausting. I liked my house, liked the space, but it ran its course.”

Buckay moved in with her boyfriend in a downmarket part of the east side, full of long-time residents too stubborn or poor to leave. And she likes it fine.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Exposed brick, check. Reclaimed wood, check. Lauren Hood, a lifelong Detroiter who sometimes visits the Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Co. to work, notes that businesses catering to newer Detroiters speak their own language. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Exposed brick, check. Reclaimed wood, check. Lauren Hood, a lifelong Detroiter who sometimes visits the Great Lakes Coffee Roasting Co. to work, notes that businesses catering to newer Detroiters speak their own language. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) Graffiti still scars the windows of an unrenovated building on Capitol Park. Residents were given one month to vacate earlier this year. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Graffiti still scars the windows of an unrenovated building on Capitol Park. Residents were given one month to vacate earlier this year. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) The Albert, formerly the Griswold Apartments, is the most often-cited example of gentrification in the central business district of Detroit. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

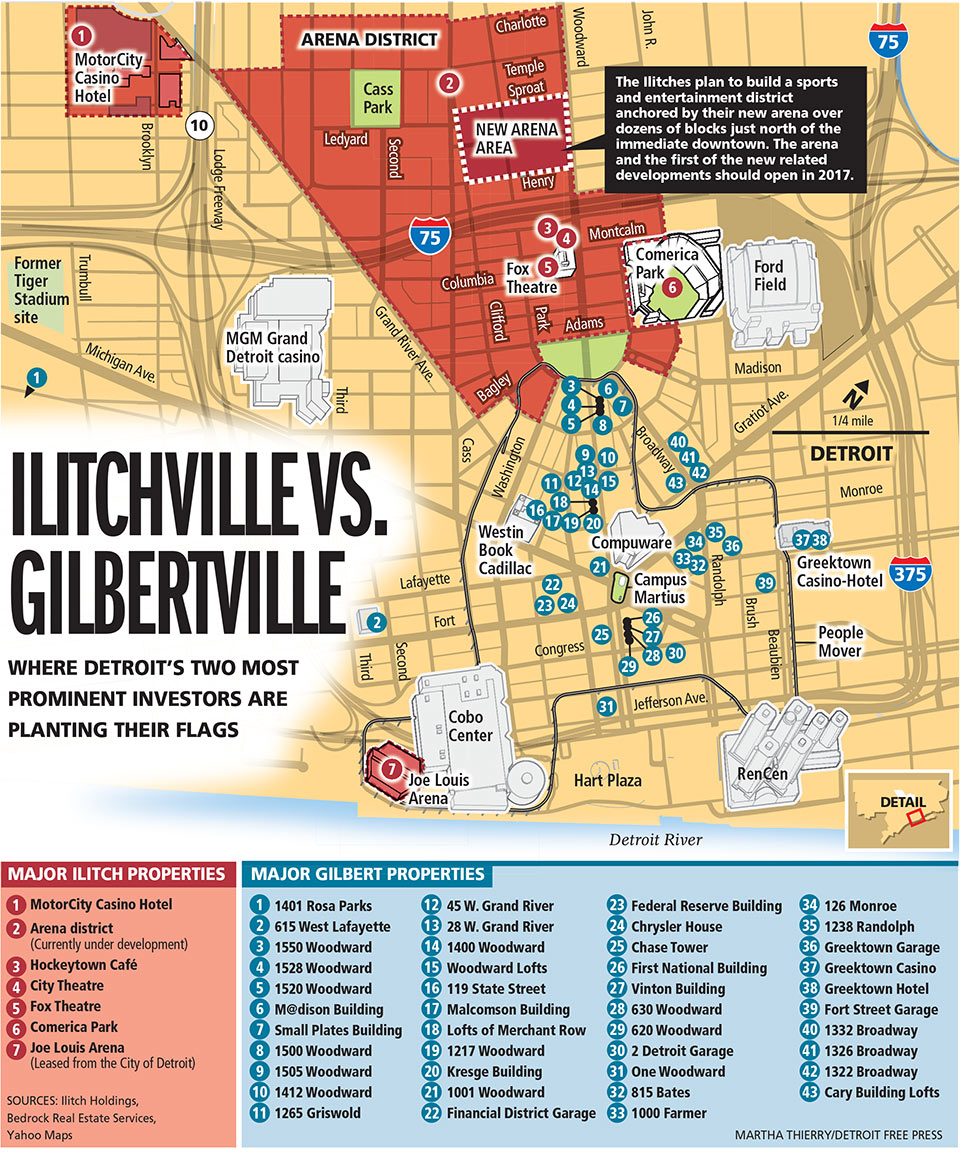

The Albert, formerly the Griswold Apartments, is the most often-cited example of gentrification in the central business district of Detroit. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer) As coffee houses, industrial lofts and gastropubs pop up across greater downtown Detroit, the city’s two major empire builders – Dan Gilbert and Mike Ilitch – are planting flags across entire neighborhoods, as this graphic from the Detroit Free Press shows. Credit: Martha Theirry/Detroit Free Press.

As coffee houses, industrial lofts and gastropubs pop up across greater downtown Detroit, the city’s two major empire builders – Dan Gilbert and Mike Ilitch – are planting flags across entire neighborhoods, as this graphic from the Detroit Free Press shows. Credit: Martha Theirry/Detroit Free Press. Austin Black’s real-estate business is booming, thanks to gentrification in the central city. He calls it a necessary part of Detroit’s recovery. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)

Austin Black’s real-estate business is booming, thanks to gentrification in the central city. He calls it a necessary part of Detroit’s recovery. (Bridge photo by Nancy Derringer)