He started the Detroit riot. His son wrestles with the carnage.

The 50th anniversary of the 1967 civil unrest in Detroit is being recognized Sunday. This story about a man who stood at the epicenter of that event was first published in Bridge last December.This story contains crude language.

As much of the city slept, 19-year-old William Walter Scott III stood at the corner of 12th Street and Clairmount, watching as police escorted scores of black patrons out of a blind pig on Detroit’s west side.

It was about 3:45 a.m. July 23, 1967. William Scott, known as Bill, was among a crowd of mostly young African Americans gathering to watch the police hustle club patrons into waiting paddy wagons. He had a particular interest in two of the people being led away.

His father, William Walter Scott II, was the principal owner of the club, an illegal after-hours drinking and gambling joint. His older sister, Wilma, was a cook and waitress. The night was hot and sticky, and the crowd’s initial teasing of the arrestees devolved into raucous goading of police as they became more aggressive, pushing and twisting the arms of the women.

“You don’t have to treat them that way,” Bill Scott yelled. “They can walk. Let them walk, you white sons of bitches.”

By the time the wagons were full, the crowd had swelled, the taunts had grown more hostile and, though police manpower was thin early Sunday, several scout cars responded to the scene. Cops stood at the ready in the middle of 12th Street, billy clubs in hand, forcing the throng back on the sidewalk.

Scott, tall and lean, mounted a car and began to preach to a crowd long accustomed to the harsh tactics of the overwhelmingly white Detroit police in black neighborhoods: “Are we going to let these peckerwood motherf------ come down here any time they want and mess us around?”

“Hell, no!” people yelled back.

Scott walked into an alley and grabbed a bottle, seeking “the pleasure of hitting one in the head, maybe killing him,” he remembers thinking. Making his way into the middle of the crowd for cover, he threw the bottle at a sergeant standing in front of the door.

The missile missed, shattering on the sidewalk. A phalanx of police moved toward the crowd, then backed off. As the paddy wagons drove away, bottles, bricks and sticks flew through the air, smashing the windows of departing police cars. Bill Scott said he felt liberated.

“For the first time in our lives we felt free. Most important, we were right in what we did to the law.”

The rebellion was underway.

A personal history

Bill Scott’s thrown bottle was a catalyst for one the most destructive civil disorders in U.S. history -- five days of looting, arson and violence in Detroit that killed 43 people and resulted in thousands of injuries and arrests in a summer jolted by violence across dozens of U.S. cities.

But Scott, a bright but troubled product of the 12th Street neighborhood, left a multi-layered legacy more enduring than broken glass. It’s a legacy that still resonates today, as the 50th anniversary of 1967 draws near and Detroit reevaluates whether the despair and tensions of that summer continue.

Three years after the looting and burning, Scott, by then 22 and a student at the University of Michigan, self-published a memoir titled “Hurt, Baby, Hurt” that describes his experiences growing up as a young black man in majority-white Detroit, working in his father’s blind pig and living along 12th Street, the west-side thoroughfare that was Detroit’s crowded and rowdy sin strip.

He writes of growing anger at what he felt was the city’s racial oppression, where Detroit’s notoriously aggressive police were not shy about knocking heads on corners where black men lingered. Bill Scott’s account of his role in the violence comes from the memoir.

In 1969, an early version of his book won a prestigious Hopwood Award, the U-M literary prize whose student winners over the years included future heavyweights Arthur Miller, Lawrence Kasdan and Marge Piercy.

Largely forgotten, Scott’s memoir reads today like a newly discovered time capsule, but one with contemporary significance amid the divide between police and African-American communities across the nation. Perhaps no other account delves in such a deeply personal way into the rage and despair that drove so many black Detroiters into the streets that summer.

Scott, who spent a childhood steeped in self loathing, embarrassed by the radical black politics of his father and secretly imagining he was white, describes his political transformation through the racial animus he said he witnessed routinely in Detroit.

But the story of Bill Scott did not begin with a thrown bottle on that July night nearly 50 years ago. Nor would it end with his subsequent downward spiral, marked by drug addiction, mental illness and homelessness.

For Bill Scott would have a son, Mandela. And that son would have his own dramatic journey -- from a privileged upbringing that led him to the Ivy League, to his own racial awakening, when he realized that no matter how carefully his life was constructed, his skin color would always set him apart from the white world he had so confidently navigated.

The saga of Bill Scott must be told without Scott himself. Now 68, he has disappeared somewhere in coastal Florida. The political fire and promise of his youth would be derailed by substance abuse and mental illness, those close to him say.

“I’d never met anyone remotely like him. It was terrifying and exhilarating,” said Auburn Sheaffer Sandstrom, who first encountered Scott in a U-M graduate class and married him four years later.

Percy Bates, a professor of education at U-M, knew Scott briefly when Scott was a child and became closer to him in Ann Arbor, when Scott showed glimmers of his potential.

“Anybody who knew him knew that he was very bright, but he was just unable to use that brightness to any positive end,” Bates said. “I think later he probably would not have been able to produce the book or anything like that that required persistent attention.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

The blind pig, also known as the United Community League for Civic Action, was on the second floor of Economy Printing at 9125 12th Street. A police raid on this illegal bar and gambling joint sparked the 1967 Detroit uprisings. (photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library)

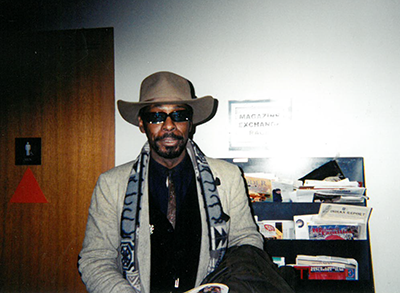

The blind pig, also known as the United Community League for Civic Action, was on the second floor of Economy Printing at 9125 12th Street. A police raid on this illegal bar and gambling joint sparked the 1967 Detroit uprisings. (photo courtesy of the Bentley Historical Library) Bill Scott (courtesy photo)

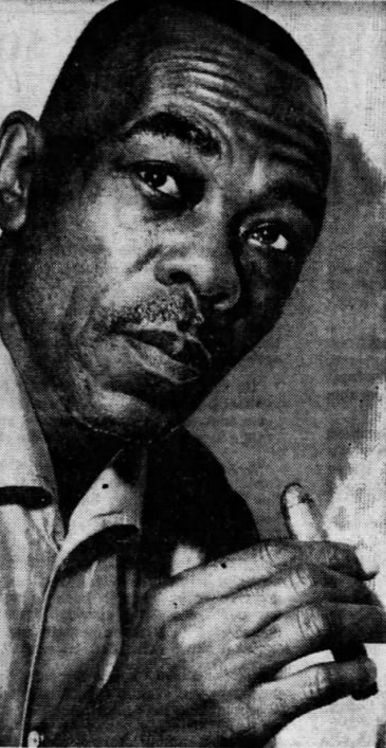

Bill Scott (courtesy photo) William Scott, director of United Community League for Civic Action, owner of the blind pig, father of Bill and Wilma Scott. (Detroit Free Press photo.)

William Scott, director of United Community League for Civic Action, owner of the blind pig, father of Bill and Wilma Scott. (Detroit Free Press photo.) Auburn Sheaffer Sandstrom, a doctoral candidate at Cleveland State University, meets with the African Wisdom Circle, an informal weekly coffee-house group in University Heights, Ohio, that includes James E. Page, left, and John Omar. The group discusses issues of race, gender and the meaning of being human. (Photo by Peggy Turbett)

Auburn Sheaffer Sandstrom, a doctoral candidate at Cleveland State University, meets with the African Wisdom Circle, an informal weekly coffee-house group in University Heights, Ohio, that includes James E. Page, left, and John Omar. The group discusses issues of race, gender and the meaning of being human. (Photo by Peggy Turbett)