He started the Detroit riot. His son wrestles with the carnage: Part 2

The father

The origins of the Scott family’s story is a familiar one in Detroit.

William Walter Scott II, the owner of the blind pig and Bill Scott’s father, was born in Georgia and came to Detroit as child, just as the “Great Migration” of African Americans from the South to a fresh start in northern cities began before World War I. The influx would boost Detroit’s black population seven-fold within a decade as the auto industry transformed the city into an industrial metropolis starving for workers.

When Bill Scott, his sister Wilma and their siblings – Tyrone, Reginald and Charlotte -- were young, their father made a good living at Dodge Main and other factories. But between 1947 and 1963 the city’s manufacturing economy hemorrhaged 134,000 jobs, triggering the start of Detroit’s long decline. William Scott lost his factory job, and subsequently the family lost its house.

Unable to find work, William Scott II turned to “the numbers,” the illegal, lottery-like gambling game ubiquitous in black neighborhoods, even as his political activism grew.

He eventually became involved in organizing black political power by training volunteers for local campaigns. His second-floor suite of rooms on 12th Street was officially known as the United Community League for Civic Action. On the night of the 1967 raid, one room contained a wall chart of local precinct delegates. William Scott’s wife, Hazel, worked in the Detroit office of G. Mennen (Soapy) Williams, Michigan’s Democratic governor from 1949 to 1961 who was popular in the black community.

But the elder Scott’s disgust with Detroit’s white political system grew. Years later, he would tell a sociologist studying the riot that political leaders pass legislation “just to control and contain the Negro.”

Mr. Scott did not hide his militancy, or his anger. He fumed at being called “boy” by police and roughly frisked for no apparent reason. In 1973, when Coleman Young was elected Detroit’s first black mayor on a police-reform platform, he told his daughter Wilma, “I can finally get off my knees.”

“All the people have had their revolutions, and we’re the last. It’s something that’s got to come, you can’t stop it. When people get sick and oppressed, they’re gonna riot,” William Scott told the sociologist.

“My father was a survivor,” said Wilma Scott, now 70, who spent more than 40 years as an office worker at Detroit’s Henry Ford Hospital. “And he was a survivor without being a criminal. Except for the numbers, which he did not feel was a crime, okay?

“To this day, I understand his logic. He was a black man that was determined just to be free. It’s as simple as that. To say he had to depend on a white man for his living – he did not like that. Especially after being in the factory and being laid off.”

The son

Bill Scott was born two years after Wilma, in 1948. In his memoir, he describes a bleak childhood of constant moves, being bullied at school and spending lonely days wandering through alleys, looking for useable junk.

He was close to his mother, but she was often hospitalized with heart problems and died when Bill was 14. He said he feared his father, writing that he beat him, though Wilma Scott says she did not witness such violence.

Bill Scott did not see his own early promise. He had trouble learning in school, and thought himself “ugly,” “dull,” “strange,” “useless,” even “mentally retarded.” By age 10, he was unruly and suffering emotional problems. He was sent to the Hawthorn Center, a state-run facility for emotionally-troubled children in Northville, and later to a similar institution, the Boys Republic in Farmington Hills. In his own mind, he wrote, he pretended to be white because, he felt, being black was bad, but white children were considered good.

It was in the early 1960s that Bates, the U-M professor, first met Bill Scott at a camp in Pinkney. The boy, he said, “didn’t trust anybody, he couldn’t get close to anybody. He was constantly acting out, calling people names, throwing stuff, hitting people. It was just clear that he had some serious issues.”

But Bill Scott received counseling at the two youth homes and met adults who mentored him. He writes glowingly of both places, and they seemed to help him stabilize.

As he moved into middle school, the unruly boy began to blossom. Scott writes of becoming intellectually curious and aware of the importance of good values: respecting women and elders; obeying the law; refraining from stealing or premarital sex. He began attending church. “I liked the sound of this heaven place,” he wrote.

After a brief, tumultuous stay in a foster home, Scott returned to his father’s temporary home, a three-room apartment near 12th Street.

It was in this rapidly changing neighborhood that Bill Scott said he bumped into the reality of being a black man in Detroit. After years in white-run institutions and attending church, his values were “almost in exact opposition to the way my people lived” back on 12th Street.

Because of his polite bearing, he was mocked by neighborhood toughs, who called him “Proper” and “Whitey.” He said he stood out because he was a “decent” person. “I didn’t have processed hair, a rag hanging from my head or dirty clothes,” he writes, “and, most of all, I had the ‘proper thoughts.’”

At Northern High, Scott noted that virtually all the students were black and most of the faculty was white, a recipe for failure, he believed. He called Northern “a nigger factory” that churned out unschooled students who wanted to learn but were at the mercy of teachers who either didn’t want to teach black students, or didn’t know how.

Test scores showed 9th graders at Northern reading at a sixth-grade level. But Scott was smart and ambitious and determined to attend college, even as his white counselor tried to steer him to vocational courses. At one point, he tried to transfer to a more competitive majority-white city school, but was refused. So he made the best of it, playing drums in the band, lettering in football, learning to pole vault and, in 1966, graduating.

Three months later, some 2,300 Northern students attracted national attention by staging a walkout and boycott to protest their poor-quality education in a school that lacked the top-notch facilities and wider opportunities enjoyed by students at mostly white city schools, such as Redford High. The protests, a sign of growing militancy among young African Americans, were an unprecedented challenge to authority, and the principal and at least two other officials lost their jobs.

As he moved through his teens, Scott began to face another fact of life for many young black men in the 1960s: the Detroit police.

Scott wrote that he tried to live like a “civilized Negro,” staying active in a middle-class black church. But as he left a church meeting one day when he was 17, cops stopped him for jaywalking across 12th Street. When Scott asked what he had done, he said one of the officers threw him against the scout car and called him “boy.” They gave him a $10 ticket. Scott wrote that he ripped it up in front of them and threw in a trash can next to their car.

Next was a run-in with the department’s notorious Big Four -- three plainclothes cops with a uniformed driver in a big car -- a unit that cruised precincts and routinely harassed blacks. Walking out of a store, Scott and brothers Tyrone and Reggie were stopped and frisked for no reason, Scott writes. The confrontation ended with Scott shouting, “You can kiss my black ass.” He said police backed off when an angry crowd began to form.

Scott’s racial consciousness continued to grow during a months-long job search in the spring and early summer of 1967 when, despite an uptick in the city’s economy, 25 to 30 percent of black youths between 18 and 24 remained unemployed. Failing to find work, he was forced to drop out of Michigan Lutheran College, a Detroit school he attended before U-M.

The frustrations piled up, along with a growing perception that his fellow church members attended services to “wallow in their own self-hatred” and ask God’s forgiveness “for being black.” He felt like he was pulling himself up by his bootstraps – as society demanded – but getting nowhere.

It was these accumulated grievances, hardly unique to Bill Scott or to blacks in Detroit, that reached a boiling point in the summer of 1967, when dozens of U.S. cities exploded in violence. At age 19, the Bill Scott who threw the first bottle at police was a young man determined to break with his past. “I decided to reject anything that was white,” he writes.

It also softened how he viewed his father.

“I began to look at the cat and see that he was farther ahead than anyone I’d met in my entire life and he was the only person I wouldn’t listen to,” Scott writes. “I guess he was the most courageous and bold man I ever saw in my life.

“I could now understand why my father had given up in the white conventional world. I was black and being black meant I had to live black…no more hating myself because I was black.”

He went to work at his father’s club.

The blind pig

There is not a street in Detroit today that resembles the 12th Street of 1967 in the stretch near the blind pig.

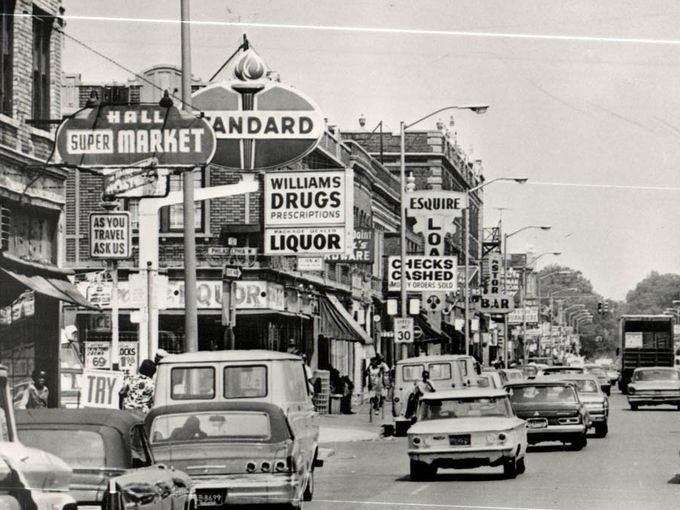

Fifty years ago, the mile-and-a-half section of 12th Street north of West Grand Boulevard was a densely packed commercial strip of markets, pharmacies, party stores, bakeries, shoe stores, beauty parlors and photo studios. With two and three-story buildings along both sides, and a constant flow of people and traffic, 12th looked like a typical Detroit shopping district when the city had 1.5 million or more residents.

Many blacks living on the side streets off 12th were upwardly mobile and already middle class. But the stretch of 12th north of Virginia Park had developed into a frenetic strip of legal and illegal adult entertainment: bars, prostitutes, pimps, pawn shops, gambling, drugs, after-hours drinking, crime and cops.

The neighborhood personified the city’s rapidly changing geography after World War II. Up through the 1940s, the area had been largely Jewish, but as Jews began moving northwest, and African Americans took their place on side streets dense with apartment buildings and solid multi-family homes.

Urban renewal projects destroyed the downtown black ghetto in the 1950s and new laws cut into housing segregation, prompting even more African Americans to flood into the 12th Street neighborhood, though store owners remained mostly white.

“Twelfth Street was like a jungle or an unsolvable maze,” Scott writes, a “Hollywood strip” filled with “shady-looking characters” hanging out on corners.

“It was hard to predict what was going to happen next – I mean one night somebody might get shot or cut up and next night everybody on the street could be happy and cool; plain drunk.”

For much of the summer of 1967, Scott earned $25 a night as doorman at his dad’s club, letting people in and trying to keep police out. The club was dark and smoky, with a bar, pool table, gambling room, kitchen and a dance floor with loud music from a juke box. ”Everyone was dancing, laughing, having a nitty-gritty-funky good time,” Scott recalled.

Blind pigs like the one William Scott operated were long an institution in Detroit’s black neighborhoods. They served blacks when African Americans were barred from downtown restaurants and bars before World War II. After the color line was broken in mainstream establishments, blind pigs continued to play a major cultural role in black Detroit, historian Sidney Fine wrote, and raids by white cops were often seen as having “racial and symbolic significance.”

Police raided William Scott’s club twice in 1966 and again in June 1967, when the vice squad arrested 28 people on misdemeanors. The DPD tried to stage other busts but couldn’t get an undercover cop past the door. Once, they burst in only to find a children’s Halloween party in progress.

As summer unfolded in 1967, police confrontations with black residents added to racial tension in Detroit. Rumors of impending unrest raged across the city amid scattered disorders in African-American neighborhoods across the country, including a small, two-day disturbance on Kercheval Avenue on Detroit’s east side in 1966. By late July 1967, violence had torn through 33 American cities, most notably Newark, where six days of violence left 26 people dead.

Detroit was still on edge from the fatal shooting in June of a black Vietnam veteran. The man had dared to take his pregnant wife to Rouge Park, then surrounded by an all-white neighborhood. Whites taunted the couple with racial slurs, pelted them with bottles and suggested they might rape the woman. Someone shot the veteran; his wife was not assaulted but would suffer a miscarriage, according to the Michigan Chronicle.

Then, on July 1, a black prostitute was fatally shot at 12th and Hazelwood. Police variously said the assailant was a pimp or a prospective customer, but rumors circulated in the black community that an off-duty white officer had killed her after she allegedly slashed him with a knife.

Bill Scott said he was at the blind pig during the police raid in June and an officer hit him in the head. He wrote that he chose to “Uncle Tom my way out” that night and play nice with police, but he fumed. The next time, he vowed, he would fight back, “hopefully to kill him if need be.”

On the early morning of July 23, 1967, Scott wasn’t working the door; his job search had finally borne fruit, and he had found a good position in an auto factory. But he writes that he drove up to the club in time “to see this honky cop swing a sledgehammer into the plate glass door.”

After Scott whipped up the crowd, threw the bottle and watched the last paddy wagon drive away, he said he entered the club to find the interior in shambles. The jukebox and wine bottles were broken; even the typewriter he used for his writing had been smashed.

He said he returned to the street and threw a litter basket through the window of a drug store, triggering an alarm and jacking up the adrenalized atmosphere on 12th Street. “I had to destroy something,” he writes.

People slowly entered the drugstore. “I wasn’t even thinking about looting at the time it all started,” Scott writes. “My interest was to strike out at something that was more powerful and more legitimate than me; at the time this was the white store owners.”

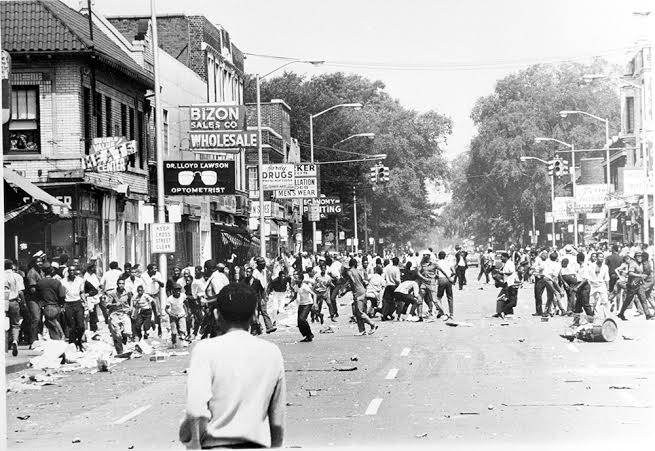

He joined others in breaking windows, and mounted a box to play traffic cop, directing drivers along the increasingly unruly street. There were no real police in sight. At one point, a “young diddy-bopper” stopped him on the street and said, “I am so glad you started this thing.”

Scott says he was staggered by the comment, as his actions began to sink in. He felt sick to his stomach, but soon recovered, believing that whatever the motivation of the looters, they shared a lack of respect for the law, “the law that had abused them and their right to live,” he writes.

“Yes, I started a riot, although it was going to happen some other time. Nevertheless, I had made it possible for cats to get those material things they desired when there was a larger human fight on hand.”

The outline for the beginning of the riot that Scott describes in his book is generally supported by official city reports and studies by historians and other experts. But while Scott is the only person to claim he started the disorder, no official or researcher ever confirmed he was the instigator.

In “Violence in the Model City,” Fine, the U-M professor, took note of Bill Scott’s account and also wrote that police identified another young man, dubbed “Greensleeves” for his green shirt and pants, who screamed at police and urged bystanders to fight back. Fine wrote that Greensleeves, Scott “and, no doubt, others, helped to communicate” their outrage to the crowd, “which probably saw the blind pig raid in the context of long-standing grievances.”

By 9 o’clock that Sunday morning, police reappeared on 12th Street. And Bill Scott went home to sleep.

Arrest, and regrets

Scott awoke Sunday afternoon to find smoke in the house, which was on a nearby residential section of 12th Street. A neighboring home was on fire, and his father figured the flames would spread before the fire department could arrive. Firefighters showed up, though, and extinguished the blaze, but it rekindled, destroying their house and most of their block.

12th Street was a chaotic scene, with sirens, fires and stunned people running back and forth, fearing for their lives. Scott went to stay with a friend.

The next morning, with widespread confusion across the city, Scott looked for a newspaper. He walked more than a mile, to the usually busy corner of Grand River and West Grand Boulevard, but the streets were deserted, with buildings burned and looted. He watched as two young men climbed through the broken window of a drugstore when suddenly a line of squad cars drove up. Scott told the police he was only watching, but they cuffed him and took him downtown.

Charged with illegally entering the store, Scott spent the next 15 days in a gulag of crowded, sweltering, stinking lockups, from the oily confines of precinct garages to stifling buses with shut windows in the July sun to the Belle Isle bath house, as Detroit Police sought innovative ways to store thousands of arrestees. He was finally released after charges were dropped.

Taking the bus back to 12th Street, Scott got off at Seward and walked past the hollowed-out neighborhood of loose bricks, broken glass and boarded-up buildings.

Days of looting, arson and sniping had left 43 people dead; 1,189 injured; more than 7,000 arrested; 2,509 businesses and homes looted or burned; and metro Detroiters rattled to their cores.

“The further I walked down Twelfth, the more I became aware of the destruction around me, which made me feel less of a man for being part of it,” he writes.

“A man doesn’t destroy his home; he protects it at all cost. This I hadn’t done; I let another man come and force me to destroy my own. This put me at his mercy. I became a boy once more. He could control me completely.”

Bill Scott spoke to his father, who was laying low, fearing retaliation from police for what had happened outside his club. Bill returned to the factory where he had found work, but was fired for missing two weeks with no explanation. His car had been towed, and he couldn’t afford to get it back. He was filled with hatred, he wrote. The thought of killing police constantly crossed his mind.

A month later, Bill Scott paid the $1.80 Greyhound bus fare and moved to Ann Arbor, “never to return,” he wrote, “until?”

That is how his book ends. But not his journey.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

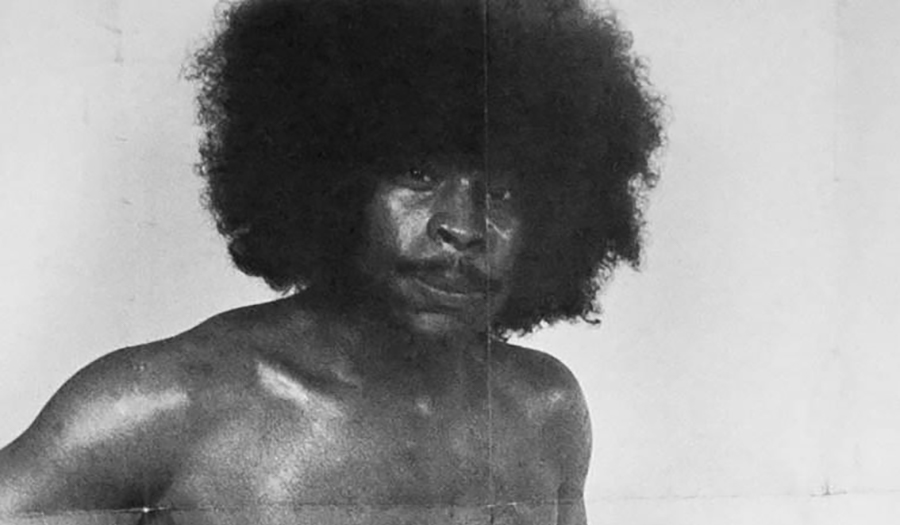

Bill Scott from a promotional poster for his book, "Hurt, Baby, Hurt."

Bill Scott from a promotional poster for his book, "Hurt, Baby, Hurt." 12th Street at W. Philadelphia in the 1960s, looking north. (Detroit Free Press photo.)

12th Street at W. Philadelphia in the 1960s, looking north. (Detroit Free Press photo.) Bill Scott’s sister, Wilma Scott, in her Detroit home in November. (Photo by Brian Widdis.)

Bill Scott’s sister, Wilma Scott, in her Detroit home in November. (Photo by Brian Widdis.) People on 12th Street on Sunday, July 23, 1967, several hours after the raid on the blind pig, which was located in the building in the left background, with the “Economy Printing” sign. (Detroit Free Press photo.)

People on 12th Street on Sunday, July 23, 1967, several hours after the raid on the blind pig, which was located in the building in the left background, with the “Economy Printing” sign. (Detroit Free Press photo.)