A quick guide to the 1967 Detroit Riot

DATES

Sunday, July 23 through Thursday, July 27

BY THE NUMBERS

Deaths: 43 (10 whites and 33 African Americans, most at the hands of law enforcement)

Injuries: 1,189

Damage: The official total was put at between $287 million and $323 million, in 2016 dollars, but that did not include losses by businesses and individuals who had partial insurance or were uninsured. It also did not include business-interruption costs and financial losses to individuals and city government, lost wages and lost retail sales outside the riot area.

Arrests: 7,231

Stores looted or burned: 2,509, including 611 food markets; 537 cleaners; 285 liquor stores; and 240 drug stores. The vast majority of damaged buildings were never rebuilt.

Homes: While the total is uncertain, Detroit was the only city in 1967 whose disorder caused significant damage to residential districts. Some 388 families were displaced.

Fires: The Detroit Fire Department responded to 3,034 calls during the seven days of the riot week. A total of 690 buildings were destroyed or had to be demolished. Two firefighters died and 84 were seriously injured. A fire expert who studied Detroit’s riot blazes concluded the “city had narrowly averted a firestorm” like those in Tokyo, Berlin other urban war zones during World War II. Dozens of suburban departments came to Detroit’s aid.

Law enforcement: It took about 17,000 members of various organizations to quell the riot: Vietnam-hardened ‒ and integrated ‒ U.S. Army troops from the 82d and 101st Airborne units; Detroit Police; Michigan National Guard; and Michigan State Police. Observers generally praised the work of the well-trained army personnel and state police. Inexperienced and largely white national guard troops received widespread criticism for their lack of discipline. There were significant reports of verbal and physical abuse by Detroit police. There were also nearly constant rumors of sniper fire which, when combined with the long work hours during the uprising, left many officers exhausted and on edge.

Percent Detroit residents who were black: About 38 percent.

Percent Detroit Police who were black: Five percent (237 of 4,326 officers).

THE RIOT IN CONTEXT

A tumultuous summer: Civil disorders of varying sizes broke out in 128 cities in 1967. Some cities had more than one riot; New York City had five. But Detroit’s disorder was by far the biggest that summer in loss of life and property damage, and is considered one of the worst insurrections in American history.

A progressive mayor: Mayor Jerome Cavanagh was a liberal visionary. In the years before the riot, “he moved farther on racial issues than any other big city mayor,” wrote historian Kevin Boyle. Cavanagh, who was white, also aggressively embraced President Lyndon Johnson’s Great Society program, and Detroit became a so-called “Model City,” receiving millions in federal funds to finance Cavanagh’s ambitious Total Action Against Poverty program. But the city’s economy deteriorated in the 1960s as it had in the 1950s. Jobs, and white residents, fled to the suburbs, and Cavanagh never was able to control the abuses and systematic denigrations of the African-American by the nearly all-white Detroit Police Department.

CHIEF CAUSES OF UNREST

Police brutality; unemployment; segregated and substandard housing and public schools; a sense of powerlessness; lack of opportunity; racism.

CHRONOLOGY

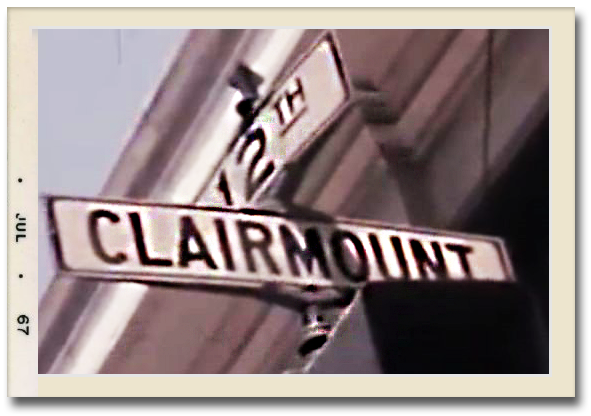

Sunday, July 23: The riot ignited when police raided a “blind pig” (an after-hours drinking and gambling club) at 12th Street and Clairmount – then a raucous commercial and nightlife district – at 3:30 a.m. Sunday. Looting and arson spread during the early morning and afternoon hours, as Detroit police officials employed a strategy of restraint, banning the use of tear gas and firearms and ordering street officers to passively contain the disturbance to the 12th Street area, where several thousand people had gathered, rather than take aggressive steps to make arrests. That initial strategy failed and was widely criticized. By 3 p.m. Sunday rioting spread west to Linwood Avenue, and the National Guard was mobilized.

Remarkably, officials Sunday morning convinced the local media to refrain from reporting about the growing disorder, though rumors circulated rapidly, and ominous plumes of black smoke arose over the near west side. Radio and TV reports started in mid-afternoon. By nightfall, rioting had spread east of Woodward. Mayor Jerome Cavanagh ordered the closing of all bars, theaters and gas stations. A 9 p.m. curfew was widely ignored.

Monday, July 24: The riot escalated on Monday, spreading along Grand River and Livernois. By daylight, sniper fire pinned down officers in precinct stations at Mack and Gratiot and St. Jean and Jefferson on the east side. By 4 p.m. 30 fires were burning out of control, as snipers and looters also harassed fire fighters. The chaos on the streets was matched by confusion among city leaders and law enforcement officials.

The rest of the week: After much haggling and vacillation among political leaders in Detroit, Lansing and Washington, battle-hardened, well-trained paratroopers were deployed Tuesday on the city’s east side, which they quickly pacified, while the National Guard struggled on the west side. On Wednesday, in one of the uprising’s most notorious episodes, three black teens were killed at point-blank range by police looking for snipers, while other young black men (and two white women) were roughed up at the seedy Algiers Motel. (Only one officer went to trial for the shootings; he was acquitted by an all-white jury).

On Thursday, Cavanagh called together city business, labor and political leaders to plan the rebuilding of the city. On Friday, President Johnson announced the formation of the Kerner Commission to study the causes of, and remedies for, more than 100 civil disturbances that year.

AFTERMATH

The 1967 Detroit uprising…

- Sparked the hiring of minorities among some Detroit businesses, especially by large companies.

- Led to the creation of the civil rights organizations New Detroit Inc. and Focus: HOPE.

- Accelerated the flight of the white middle class (along with jobs) to the suburbs, a trend that actually began in the early 1950s.

- Prompted passage by the state legislature of the Michigan Fair Housing Act, to combat residential segregation.

- Started a trend of high-crime rates – especially homicide – and arson fires that continued for decades.

- Ignited deep paranoia among white Detroiters and suburbanites as rumors spread for more than a year about the possibility of another riot.

- Led to a “Riot Renaissance” architectural style of cement-block windows, barbed wire, security guards and led city institutions and entertainment venues to provide “secure, well-lighted parking.”

- Led to the election of Coleman Young as Detroit’s first black mayor in 1973.

- Gave rise to Detroit’s image internationally as a volatile urban war zone, an image the city is still trying to shed.

THE RIOT IN POPULAR CULTURE

Songs with a riot theme:

“The Motor City is Burning,” by Detroit-based blues legend John Lee Hooker; it was later covered by the MC5, which changed some of the lyrics, substituting, for instance, “Gestapo” for “police.”

“Black Day in July,” by Gordon Lightfoot.

“Det.riot ‘67,” by Moodymann (Kenny Dixon Jr.), a Detroit-based techno/house musician.

David Bowie’s “Panic in Detroit” is sometimes described as inspired by the events of 1967, but it is also said to be based on his friend Iggy Pop’s recollection of the city’s revolutionary era during the late 1960s.

Books:

“Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967,” by Sidney Fine. The 648-page tome by the late University of Michigan historian remains the definitive account of the riot.

“The Algiers Motel Incident,” by John Hersey. The famous chronicler of Hiroshima after the atom bomb examined the execution-style deaths of three young black men during the riot in a motel at Virginia Park and Woodward.

“Whose Detroit?: Politics, Labor, and Race in a Modern American City," by Heather Ann Thompson. Thompson sorts through the riot’s aftermath, including white flight, radical labor activism, conservative white homeowners, radical white activists and the election of Mayor Coleman Young.

“The Origins of the Urban Crisis: Race and Inequality in Postwar Detroit,” by Thomas J. Sugrue. Published 20 years ago, “Origins” became famous for its multi-faceted description of Detroit’s decline and its obliteration of the idea that the riot was largely responsible for the city’s 21st-Century woes.

“The Anatomy of a Riot: A Detroit Judge's Report,” by James H. Lincoln.

“The Detroit Riot of 1967,” by Hubert G. Locke.

“them,” Joyce Carol Oates’ 1969 novel, contains important scenes that take place during the riot.

“Middlesex,” Jeffrey Eugenides’s 2002 novel, also uses the riot as a backdrop.

SOURCES

“Violence in the Model City: The Cavanagh Administration, Race Relations, and the Detroit Riot of 1967,” by Sidney Fine; Detroit Free Press, Detroit News; The Detroit Almanac, “After the Rainbow Sign: Jerome Cavanagh and 1960s Detroit,” by Kevin Boyle.; Report of the National Advisory Commission on Civil Disorders;” Seven Fires: The Urban Infernos That Reshaped America,” by Peter Charles Hoffer.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Photo courtesy of the Reuther Library

Photo courtesy of the Reuther Library