Redesigning Detroit: Mayor Duggan's blueprint unveiled

Detroit Mayor Mike Duggan is a disciplined speaker whose message rarely varies from the nitty-gritty ways he and his administration are repairing the wounded city they inherited: Improving emergency response times, auctioning vacant homes, turning on street lights, demolishing abandoned property and trying to lower auto insurance rates.

The mayor does not appear to consider himself a master builder, and virtually never talks about what grand vision he might have for Detroit beyond a community that works like most large American cities.

Yet inside Duggan’s administration, his top officials are working on groundbreaking plans that could transform large swaths of Detroit. If the plans come to fruition, they could turn the city into a global showplace for how struggling cities can capitalize on shrinking populations.

Cox and his aides are drawing maps that throw out traditional neighborhood boundaries and combine largely vacant areas of the city areas with more stable neighborhoods nearby.

Led by the newly hired director of planning, Maurice Cox, a nationally known urban designer who last worked in New Orleans, the administration is quietly formulating a strategy to reimagine Detroit’s neighborhoods to take advantage of what has long been considered one of the city’s biggest problems: vacant land. It’s a “greening” strategy built on a blueprint laid out by Detroit Future City in 2013, but with a twist:

Cox and his aides are drawing maps that throw out traditional neighborhood boundaries and combine largely vacant areas of the city with more stable neighborhoods nearby. The purpose of the new districts is to take existing empty green space, refashion it, and use it to benefit both the distressed and stable neighborhoods.

“This is a very different way of thinking of neighborhood development,” Cox told Bridge recently in a bare office at city hall that had several maps of Detroit neighborhoods on the floor.

“It’s thinking about the vacancy (in troubled areas) in conjunction with stable neighborhoods which are right next door, and it’s all a part of one unit,” he said.

Cox, reaching for a map, pointed to Rosedale Park, Grandmont and Brightmoor, three neighborhoods in northwest Detroit. Rosedale and Grandmont are stable areas mostly filled with gracious brick homes and landscaped lawns. Brightmoor has long been one of Detroit poorest areas, with extensive blight and vacant land.

“Whenever we map the city, we never map Brightmoor without mapping Brightmoor, Grandmont, Rosedale,” Cox said.

And the reason for that, he said, is that Brightmoor’s vacant land can be turned into productive acreage that works for both its remaining residents and those in nearby Rosedale and Grandmont.

What constitutes “productive” land? Cox said empty lots in Brightmoor will be remade for recreation, nature, agriculture or so-called green and blue infrastructure, with engineered plots of land with plants and trees to dispose of stormwater or alleviate air pollution. Along with its blight, Brightmoor already has some of the most extensively developed agriculture in the city. Cox said Brightmoor residents eventually will benefit by living near carefully landscaped property, including parkland and wooded areas, rather than amid the wild and trash-filled parcels that mark many parts of the landscape now.

“We will have a strategy of how to steward that land, that vacant land within the city, and make it contribute to why someone would actually want to live in Grandmont-Rosedale,” Cox said.

He was less specific when asked about funding for the plans, or when residents might start to see construction. On August 7, officials announced $8.9 million in federal funds will be spent for storm management in three Detroit neighborhoods, including for green infrastructure in Brightmoor.

Building on Detroit Future City

The idea of using Detroit’s vacant land for innovative purposes beyond agriculture has been percolating among experts and various community groups for several years, but such discussions have been largely theoretical beyond the city’s numerous vegetable gardens and such projects as the “green corridor” of trees that the Greening of Detroit organization quarterbacked last year along the Southfield Freeway to reduce storm-water runoff, pollution and noise while providing shade and a non-motorized greenway around the city. Repurposing the city’s vacant land was one of the foremost proposals of the Detroit Future City recommendations unveiled in 2013, and significant green infrastructure plans have been hatched even before the Aug. 7 announcement.

What’s new is the Duggan administration’s plans, never officially announced, to yoke together neighborhoods in overhauling vacant land. Cox’s description of the plans he and officials from several departments are drawing up marks the first time city officials have moved on implementing a broad strategy, influenced by Detroit Future City, aimed at making over the empty parcels and linking them with thriving neighborhoods.

Detroit Future City (DFC) is the sophisticated and somewhat controversial planning framework that was the product of the administration of former Mayor Dave Bing and seven philanthropies: Kresge Foundation, Ford Foundation, W.K. Kellogg Foundation, John S. and James L. Knight Foundation, Hudson Webber Foundation and the Community Foundation for Southeast Michigan.

DFC’s influence has rarely been acknowledged as playing such an influential role in how Duggan and his aides are envisioning tomorrow’s Detroit.

The vacant-land strategy, while designed to help depopulated areas, is also intended to bolster stable neighborhoods by creating nearby land for recreation or nature. The DFC framework also recommends strengthening vibrant districts, a strategy Duggan has already pursued through demolitions, vacant-house auctions, side-lot sales and nuisance-abatement lawsuits in specific neighborhoods.

Taking other maps off the floor, Cox looked at far east-side neighborhoods centered around E. Warren Avenue and Cadieux, and, on the west side, around W. McNichols and Livernois, between the University of Detroit Mercy and Marygrove College. Both maps have thick red lines that tie together the prosperous districts with nearby areas that contained acres of city-owned land filled with abandoned houses and overgrown lots.

Cox was firm on one important point: Under the new plans, no one will have to move from the largely vacant neighborhoods, a fear among many Detroit residents who recall urban renewal projects that displaced thousands of Detroiters, notably African Americans, from the 1950s through the 1980s.

Cox said that fixing up the shabby, and what he called “intimidating,” abandoned property will enhance the surroundings for those who remain. The challenge, he said, is to make sure the land has the rural look that many of the remaining residents in these ramshackle areas say they want.

“Some of us who think of cities in their most urban face kind of forget that people have enjoyed a kind of rural lifestyle within the city,” he said.

“I used to think, ‘Isn’t this a problem?’ And then I’m running into people who say ‘No, I enjoy the fact that I have space around my house.’ The challenge is, is it contributing? I mean, is it beautiful? Or is it unkempt?”

Keep residents involved

John George, president of the Brightmoor Alliance a collection of community groups and nonprofits, and founder of Motor City Blight Busters, called the hiring of Cox “another brilliant move by this mayor.”

“They are basically co-signing on what we have known for over 30 years,” he said. “If you can eliminate the blight, you can create community assets. I get what they are doing. I support it.”

Tom Goddeeris, executive director of the Grandmont Rosedale Development Corporation, said he met Cox recently when he came to the neighborhood to discuss strengthening the commercial corridor along Grand River Avenue, another of Cox’s priorities. Cox didn’t talk about his land-transformation plan, but Goddeeris said the general outlines make sense.

“A key to rolling it out will be to consult the people who live in those areas as early as possible,” he said. Engaging residents at every stage was a key component of the DFC plan.

Peter Hammer, director of the Damon Keith Center for Civil Rights at the Wayne State University Law School, which promotes the educational, economic and political power of underrepresented communities across southeast Michigan, has criticized DFC for limiting its planning solutions to Detroit – as opposed to looking at regional possibilities – and for what he said was the plan’s failure to address the issue of race.

The Brightmoor-Grandmont-Rosedale plan, he said, eventually will have to be evaluated on such questions as “What are the impacts on real peoples’ lives? How much authentic community engagement is there?”

DFC’s history

“I felt like, wow, here’s a community that has accepted that it is not going to grow everywhere” ‒ Maurice Cox, Detroit planning director

Detroit has lost more than 60 percent of its 1950 population of 1.8 million. As abandoned buildings and houses were torn down, the result – vacant land – has vexed mayors for decades.

As Duggan tears down abandoned homes at a rapid pace – he said the city demolished 150 houses during a week in late July – the amount of empty land continues to grow. It’s now 23.4 square miles, according to Dan Kinkead, Detroit Future City’s interim director, or roughly 17 percent of Detroit’s 140 square miles.

In the 1970s, as the population fell and empty land began to expand, the city enclosed many of the vacant acres in central Detroit with white wooden fences that resembled farm stockades. But the vast, open fields kept growing. In 1993, the city ombudsman, Marie Farrell-Donaldson, ignited an uproar in the city – and news coverage nationally – when she proposed moving residents from mostly abandoned neighborhoods into city-owned homes elsewhere. The depopulated neighborhoods would be sealed, stripped of services and declared off limits, supposedly saving tax dollars. That plan went nowhere, but fear of forced removal has remained strong among Detroiters who live in marginal neighborhoods.

Until the past several years, most mayors over the past half century devised policies intended to repopulate Detroit’s emptying neighborhoods; they proposed filling empty land with redevelopment, such as housing. While a number of new homes have been constructed, that was hardly a widespread solution as Detroit’s massive geographic footprint continued to empty out, losing 25 percent of its population between 2000 and 2010 alone.

Urban designers have long proposed various shrinking solutions for distressed cities, and the idea of re-thinking Detroit’s vacant neighborhoods became an issue during the mayoral campaign in 2009 after Kwame Kilpatrick had resigned as mayor in 2008.

The winner, Bing, acted on the notion, and went to the Troy-based Kresge Foundation in 2010 and asked for help in planning. He told Kresge officials what had been clear for decades: that Detroit did not have the resources to serve its 140 square miles, recalled Laura Trudeau, managing director of Kresge’s Detroit and community development program.

Trudeau said Kresge suggested a process that combined a planning team of local and national experts with significant community input, and that’s how Detroit Future City was born. The process included hundreds of meetings and survey responses from 70,000 people. It was controversial at times. Some larger community meetings degenerated into shouting sessions. Bing suggested residents of depleted neighborhoods might have to move. Kresge and city hall sometimes butted heads, though Rip Rapson, Kresge's president and CEO, said some media coverage of the reported rift was "completely out of context."

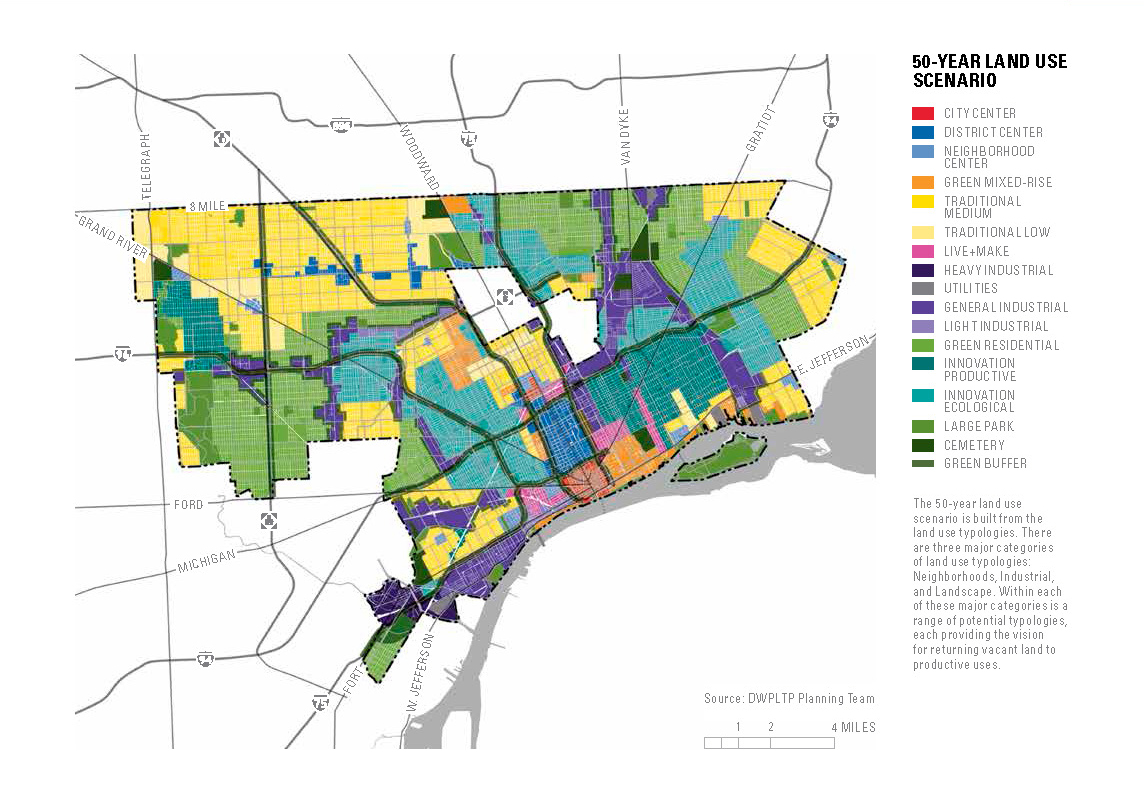

In January 2013, officials unveiled the 347-page Detroit Future City strategic framework in a celebratory news conference headed by Bing and Rapson, who said Kresge would spend $150 million over five years on projects aligned with DFC recommendations. The plan comes in a book with multi-colored maps, charts and hundreds of proposals about how Detroit can look in 50 years, if the plan is implemented.

Joining vacant areas to stable neighborhoods was mentioned on one page. Among the plan’s most prominent proposals was to more heavily populate residential and commercial areas and take advantage of the empty land. But the plan fell out of the headlines after the launch – until Duggan and Cox came along.

Less than two months after Detroit Future City was unveiled in January 2013, Gov. Rick Snyder declared the city was in a financial emergency. For the next two years, the plan was overshadowed as officials were consumed with the Detroit’s bankruptcy and mayoral election, which Duggan won.

To keep the DFC flame burning, though, city and philanthropic officials opened a Detroit Future City implementation office in 2013 that has worked quietly to coordinate planning efforts among a variety of community, government and nonprofit groups around such projects as small-scale green infrastructure and marketing for the old industrial corridor along Mt. Elliott Avenue north of I-94 on the near northeast side. Kresge continued to make grants aligned with the plan.

Under a microscope

Supported by philanthropy but tethered to city government through one of its development arms, the Detroit Economic Growth Corporation, Detroit Future City has remained a vague entity to many residents and observers.

That status got murkier in June when it was announced that Ken Cockrel Jr., the former Detroit City Council President who served a short time as mayor in 2008 and 2009, would leave his job as executive director of the implementation office and the office would be reorganized as a nonprofit with a new director.

Since taking office, Duggan has hardly ever spoken in public about Detroit Future City. In 2013, when the DFC plans were unveiled and he was running for mayor, he called it “a very valuable contribution.” In February 2014, his development czar, Tom Lewand Sr. was quoted in the Free Press as calling the book his bible.

But the city’s quiet development plans are being watched around the country.

Observers, such as Janice Bockmeyer, a professor of political science at John Jay College in New York, are paying attention to how foundations, like Kresge, collaborate with a city bureaucracy with fewer of its own planners on staff.

Bockmeyer, who is researching the democratic implications of Detroit’s planning process, wrote that foundations, with their welcome grants to cash-strapped cities, become “critical decision makers.”

June Manning Thomas, a professor at the University of Michigan’s Taubman College of Architecture and Urban Planning, who has written extensively about Detroit’s planning history, said, “I’m a little concerned that the philanthropy agencies are making decisions as to what is a viable neighborhood.”

Kresge’s Trudeau said philanthropic organizations work to build consensus within communities, not make decisions for them. She cited an initiative called Kresge Innovative Projects: Detroit, which solicits applications from across the city from community-based organizations seeking to transform their neighborhoods.

“Our 18 projects of up to $150,000 were funded in the first of its three years," she said. "That’s how the Detroit Future City framework is being brought to life by people all over the city.”

A vision in focus

Cox, 55, grew up in Brooklyn, N.Y., and came to Detroit from New Orleans, where he was director of the Tulane City Center and associate dean for community engagement at the Tulane University School of Architecture. He served as mayor of Charlottesville, Va., from 2002 to 2004 and two terms on the city council; he was also an architect on the faculty of the University of Virginia.

Cox lives in Lafayette Park with his wife and bikes to his office in Detroit’s City Hall. In June, during a conversation with CNN’s Suzanne Malveaux at the Max M. Fisher Center during a national conference of urban activists, Cox compared his new job to riding a roller coaster.

“Every day I go from being elated by what I see in terms of incredibly resilient people to being disgusted that we’ve allowed it to get to this point; wanting to stop by the side of the road to shed a tear just because I am overwhelmed that I see these majestic buildings that are still standing and they are like testaments to how great this community still is, and they so very much need some attention, some reuse, some imagination.”

Asked by Bridge about the influence of the DFC on his work for Duggan, Cox said the plan “reframed the conversation that Detroit was having about its development” by saying the city needs to pursue a higher density of housing and commerce and concentrate it in neighborhoods that already are viable, all while putting vast areas of empty land to productive use.

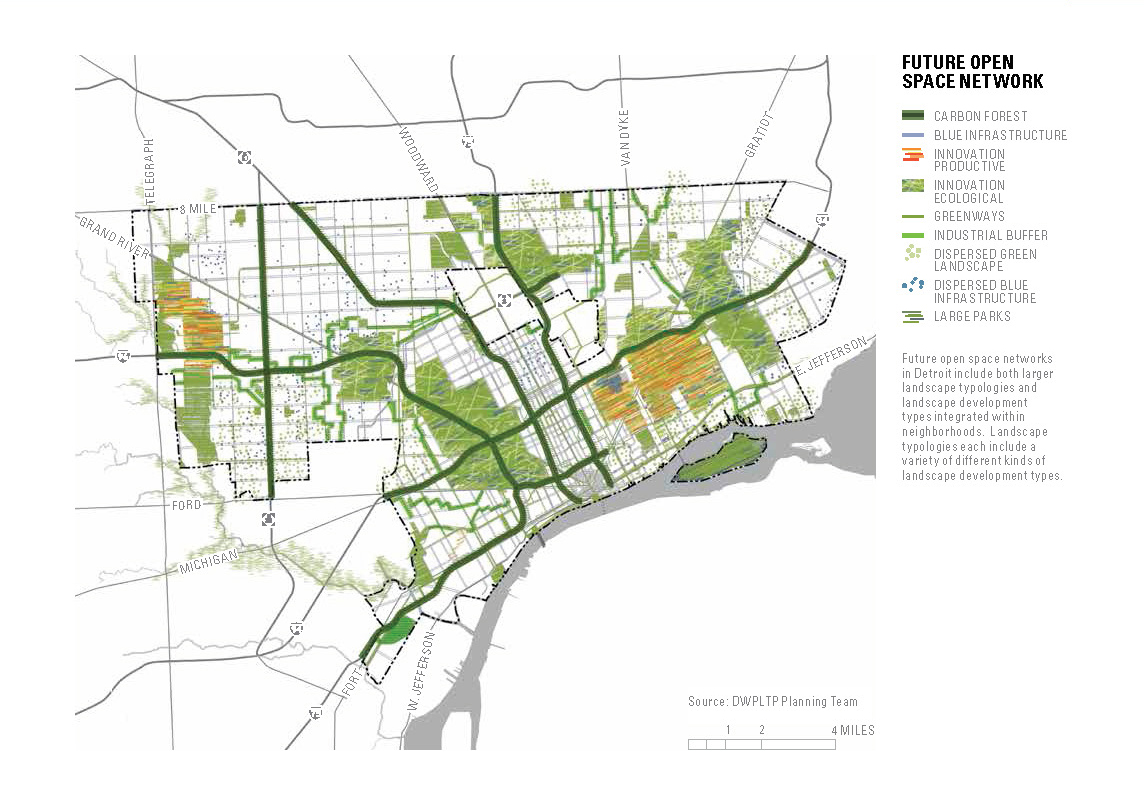

“It had a whole menu of buzz words like ‘blue infrastructure’ and ‘green infrastructure,’” Cox said, “a strong kind of environmental ethic.

“I felt like, wow, here’s a community that has accepted that it is not going to grow everywhere. And Detroit Future City gave Detroit that template. It said there are these large swaths of land where you don’t need to grow your population. You can grow your population over here” in stable neighborhoods.

“I think mayor Duggan kind of ingested that message and it emerged in his framing of our work of looking at the areas that are stable and make them stronger. Look at the areas that are stable and remove all blight. And find a way to turn the land surrounding these adjacent neighborhoods into a quality of life amenity, as opposed to a drag on those neighborhoods.”

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

Nadia Dolphus, 7, and Shanna Bennett, 19, with A "Youth Grow Brightmoor" sign Shanna painted for one of numerous agricultural projects in the neighborhood. City officials see places like Brightmoor as pivotal to transforming Detroit's vacant land into productive assets. (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw)

Nadia Dolphus, 7, and Shanna Bennett, 19, with A "Youth Grow Brightmoor" sign Shanna painted for one of numerous agricultural projects in the neighborhood. City officials see places like Brightmoor as pivotal to transforming Detroit's vacant land into productive assets. (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw) Future open-space networks in Detroit could include both large and small green areas, and they could exist inside and outside of neighborhoods, according to the Detroit Future City framework. The open spaces could contain such features as lakes, retention ponds, parks, swales, recreation areas and green buffers. Credit: Detroit Future City

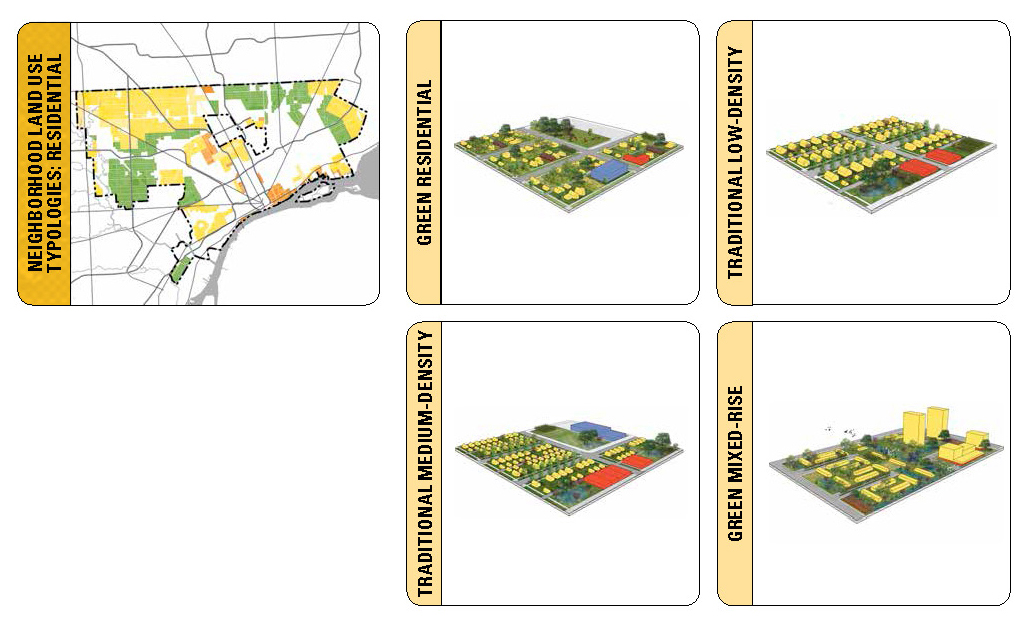

Future open-space networks in Detroit could include both large and small green areas, and they could exist inside and outside of neighborhoods, according to the Detroit Future City framework. The open spaces could contain such features as lakes, retention ponds, parks, swales, recreation areas and green buffers. Credit: Detroit Future City Green areas inside residential neighborhoods could make Detroit a leader in sustainable land use, the Detroit Future City framework said. Credit: Detroit Future City.

Green areas inside residential neighborhoods could make Detroit a leader in sustainable land use, the Detroit Future City framework said. Credit: Detroit Future City. Brightmoor, in northwest Detroit, already has an extensive green corridor of gardens, small orchards and seed gardens along Chalfonte Street, west of W. Outer Drive. (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw)

Brightmoor, in northwest Detroit, already has an extensive green corridor of gardens, small orchards and seed gardens along Chalfonte Street, west of W. Outer Drive. (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw) Graffiti on an abandoned building in a depopulated neighborhood at 31st and Buchanan on the west side reflects uncertainty in many areas of the city. It says, "The DFC plan says this hood has no future." (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw)

Graffiti on an abandoned building in a depopulated neighborhood at 31st and Buchanan on the west side reflects uncertainty in many areas of the city. It says, "The DFC plan says this hood has no future." (Bridge photo by Bill McGraw) Detroit Future City's map sees the way land could be used in 50 years. Credit: Detroit Future City.

Detroit Future City's map sees the way land could be used in 50 years. Credit: Detroit Future City. Maurice Cox is Detroit's new director of planning (courtesy photo)

Maurice Cox is Detroit's new director of planning (courtesy photo)