Auto rates drive Detroit voters into hiding

Alok Sharma analyzes data for a living. In 2010, he had a client, a politician, who was running for office and wanted to know if it was worth his time to campaign door-to-door in Detroit’s high-rise apartment buildings. Sharma thought the answer might be found by running a high-rise address through the Qualified Voter File, a public document of every registered voter in Michigan. He chose his own: the Kales Building, with 18 floors overlooking Grand Circus Park and 116 one- and two-bedroom apartments.

It is, Sharma said, full of young professionals like him, as well as empty-nesters -- just the type of middle-class people who are likely to be engaged, active voters. When Sharma looked, the building was fully occupied.

Yet he found only nine names in the Qualified Voter File – counting his own.

With Detroit facing a city election this year under the shadow of a newly appointed state emergency manager, Bridge Magazine performed Sharma’s experiment with six other buildings in Detroit’s hot neighborhoods of downtown, Midtown and Corktown.

The results, while not as dramatic as Sharma’s at the Kales Building, show voter participation rates far below 64.7 percent -- Michigan’s turnout in the 2012 general election -- and even below the city’s turnout of 50 percent.

LARGE BUILDINGS, SMALL ELECTORATES

What’s more, there’s a widely agreed-upon reason for this self-disenfranchisement:

Not politics, but the high cost of auto insurance.

In insurance, Detroit address is costly

Vince Keenan, founder of Publius.org, a Michigan voter-education and civic-participation program, says the link between insurance rates and one’s registered address is “the most well-known single fact” about voting in Detroit. And he doesn’t like it.

“It’s an unintended consequence of Motor Voter,” he said, or the National Voter Registration Act of 1993, which tied voter registration to one’s driver’s license. “It was very successful at getting people registered, especially in Michigan, because we drive so much. But by marrying the two, we have to think about (the auto-insurance issue), and we shouldn’t have to. For a voter to have to worry about where their car insurance is, is stupid. We’ve made it easier to commit community fraud, where you’re living and working in a community that you’re not voting in, than to commit insurance fraud.”

Keenan knows the price of honesty from experience. In 2002, he moved two blocks -- from one block north of Eight Mile Road, in Ferndale, to one block south, in Detroit, and saw his annual premium jump from $1,700 to $3,700.

“We need voters in Detroit who are active and engaged about it. Where you choose to vote should not be governed by your car insurance, period.”

DETROITERS PAY MORE FOR AUTO INSURANCE, BUT HOW MUCH MORE?

Michigan residents pay the eighth-highest prices for auto insurance in the country, according to the Insurance Institute of Michigan. But Detroit residents can pay even significantly more than that; as Keenan discovered, double or even triple what suburbanites pay. No one knows for sure how many people live in the city who carry driver’s licenses with addresses outside it. City residents, though, are sure the problem is widespread.

“Everybody talks about it, obviously it’s something a lot of people are doing,” said one 25-year-old man we’ll call Scott.

Scott lives downtown, but is registered to vote in a suburb west of Detroit. The same address is on his driver’s license, and his insurance company believes that’s where his car is parked. He is politically active in Detroit, and has worked for candidates. But when he does the math, he has to ask himself a question:

“Is my vote worth the few thousand dollars it would cost me? No campaign (from a Detroit candidate) could ever convince a significant number of people to suffer that pain.”

The Insurance Institute of Michigan reports the average Michigan auto-insurance customer pays $1,073.52. IIM’s Pete Kuhnmuench said his group does not calculate separate figures for individual urban areas, due to wide disparities between insurers' quotes and discounts. The state of Michigan also does not provide data on city-level averages.

If detected by their insurers, people like Scott could face consequences ranging from cancellation of their policies to recovery of the higher premiums they should be paying.

Influx of people, but where are the voters?

Amid the catastrophic financial news coming out of Detroit in recent months, the in-migration of younger people has been a bright spot -- and a national story. A 2011 New York Times story proclaimed an influx of the “young and entrepreneurial” downtown, describing a pair of 37-year-old men yearning for apartments in the nearby Broderick Tower. At the recent Detroit Policy Conference, held by the Detroit Regional Chamber of Commerce, keynote speaker Matt Cullen touted the 97 percent occupancy rate of downtown and Midtown apartments, with new construction in the works and the beginnings of a vibrant, tech-based entrepreneurial culture in the same neighborhoods.

These new residents have helped breathe life into the central city, but, at the same time, many are depriving themselves of the simplest tool of democracy -- their vote.

Studio 1 Apartments on Woodward Avenue offers “urban living at its best,” according to its website, “an artsy, safe, vibrant place to live, study, work, play and proudly call home.” Out of 124 units, just 30 people voted in the November 2012 election.

The Park Shelton, a 226-unit condo complex near the Detroit Institute of Arts, with a mix of owners and renters, sent 113 voters to the polls.

| Election is when?The city's election page offers the curious more than 20 language options, ranging from Bulgarian to Maltese to Urdu. What it doesn't offer is actual calendar information about the next city election.The primary is Aug. 6. The general election is Nov. 5. |

The precise number of voting-age adults living in those buildings isn’t public record, and changes often. But using census data, Bridge was able to calculate a rough estimate of voter participation in these high-density units, based on how many votes were cast in the November 2012 election, divided by the number of units multiplied by the city’s approximate adults per household -- 1.38. The result was 32 percent. Even assuming the leanest possible occupancy of one adult per unit, the rate only rises to 45 percent.

To be sure, voting rates in cities can be less than impressive. A recent municipal primary in Los Angeles, for instance, turned out only 21 percent of registered voters. But 2013 promises to be a pivotal year in Detroit, with a mayoral race shaping up, as well as the first city council elected by district in nearly a century, following a rewrite of the city’s charter. Detroit residents have more reasons than ever to vote where they live.

Can auto rates be that high?

But how much would voting cost the many who now sit out elections? While rates vary widely from company to company, and from customer to customer, the state published, in 2008, a rate-comparison survey, covering several different customer profiles -- married, single, with and without children. It shows customers with Detroit addresses pay sharply more than those in other metro areas, and even cities like Warren, which abuts Detroit on the other side of Eight Mile Road. (A revised guide is planned for later this year.)

The rates are an irritant to those registered in Detroit, many of whom say they don’t blame the scofflaws, mainly because they were once scofflaws themselves.

“When I first moved down here, I kept my permanent address at my mom’s house,” said Peter Van Dyke, 31, who owns two condos in the Midtown area, living in one, renting the other.

“When I lived in the Park Shelton, and worked one mile away, I drove from one 24-hour secure parking structure to another, where I would leave my car,” Van Dyke explained. “And the rate was triple. My car spends 24 hours a day in a secure parking garage. It’s probably one of the safest cars in Michigan.”

He was eventually able to negotiate an affordable rate with his agent, but it took some hard bargaining, relying on goodwill built through years of business with his family, to put in place. It’s not something everyone can do.

City’s voter records questionable

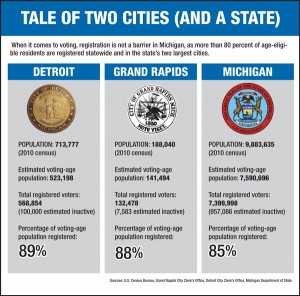

Detroit had, as of the November 2012 election, 568,854 registered voters, although Janice Winfrey, the city clerk, believes about 100,000 of those are inactive, individuals who have left the city and vote elsewhere.

Inactive voters may remain on the rolls for years; two long-gone ex-Detroiters who appear in the Qualified Voter File as Park Shelton residents are former Mayor Kwame Kilpatrick and his wife, Carlita, who very publicly moved to Texas after he resigned his office in 2008. Winfrey said her office can only purge voters in cases of death or if at least three mailings are returned as undeliverable, at which point they’re put on a countdown and, after two federal elections, may be removed.

Winfrey doesn’t see the self-disenfranchisement of the city’s new residents as a widespread problem, however.

While she’s troubled by the idea of potential voters taking themselves out of the pool, “based on our numbers and what we see on Election Day, no, it’s not a problem.”

Detroiter says auto barrier can be scaled

Matt Clayson thinks it’s a problem, however. One of the roughly 30 conveners of Declare Detroit, a political movement speaking for many of these new arrivals, sees it as fundamentally undermining the process.

“Any healthy political environment needs an inflow of new ideas and perspectives,” Clayson said. “When those new ideas don’t engage in the process, it makes it difficult to have representation that addresses their needs.”

Clayson, like most young Detroiters, is well-acquainted with the insurance problem. But he thinks it’s not as big as many think it is.

“There are some myths around insurance rates in the city,” he said. “If you shop around, you can find very reasonable rates. Maybe not Brighton rates, but at the same time, it won’t be a 100 percent increase.” Clayson, who lives in the Indian Village neighborhood northeast of downtown, found his coverage through Progressive, and pays about $2,000 a year to insure two cars. That’s about 20 percent more than he would pay outside the city, he estimates.

“To me, an hour shopping around is worth the right to vote in Detroit, and to make one’s voice heard.”

Others think the problem may be one of demography. Younger people move often, and often don’t feel rooted to a place -- and hence, inclined to vote on local issues -- until they settle down.

“When (residents buy rather than rent), people take more pride of ownership, in the property and in the city,” said Ryan Cooley, owner of O’Connor Real Estate in Corktown and, along with his parents and brother, an investor in the steadily gentrifying neighborhood.

“People move in, test the waters, and then they end up coming back and buying. Then they participate,” Cooley said.

In the meantime, their non-participation does them no favors. Former state Rep. Tim Bledsoe, who left office in 2012 to return to his work teaching political science at Wayne State University, remembers walking the Detroit part of his district, using registered-voter lists to find homes with likely voters.

“You’d see a car in a driveway with political stickers on it, but the lists said no registered voter lived there,” he said. “It’s frustrating, You’re looking for voters, you know there are people there who are politically engaged.” What’s more, he said, the shortage of younger people in voter rolls “shapes the thinking of politicians. Any politician campaigning in Detroit who knows what he or she is doing, ends up focusing on seniors.”

Staff Writer Nancy Nall Derringer has been a writer, editor and teacher in Metro Detroit for seven years, and was a co-founder and editor of GrossePointeToday.com, an early experiment in hyperlocal journalism. Before that, she worked for 20 years in Fort Wayne, Indiana, where she won numerous state and national awards for her work as a columnist for The News-Sentinel.

See what new members are saying about why they donated to Bridge Michigan:

- “In order for this information to be accurate and unbiased it must be underwritten by its readers, not by special interests.” - Larry S.

- “Not many other media sources report on the topics Bridge does.” - Susan B.

- “Your journalism is outstanding and rare these days.” - Mark S.

If you want to ensure the future of nonpartisan, nonprofit Michigan journalism, please become a member today. You, too, will be asked why you donated and maybe we'll feature your quote next time!

CLICK TO ENLARGE

CLICK TO ENLARGE